The interest on technical debt

‘Thomas, we want to add a new feature to our production system. How long will that take?’

Thomas looks at the code. Then the database. He can’t look at the documentation; there isn’t any.

His answer: ‘The feature itself? 10 days. Implementing it properly? 3 months.’

The caller’s reaction: ‘EXCUSE ME?’

The response is not surprising. It is based on a perception that consistently overlooks a central aspect of software development. The new feature is relatively easy to implement, but everything else becomes a problem:

- Eight years of accumulated code.

- No automated tests.

- Business logic distributed across hundreds of database procedures.

- One change leads to three adjustments in other places.

Adding a new feature to such a system is like playing Jenga: you pull out a block and hope the tower doesn’t collapse.

The hidden costs:

- The feature itself: ten days of development, around £9,000.

- Risk mitigation: testing, documentation and review, around ten weeks, approximately £45,000.

- And if something goes wrong: production downtime, bug fixing, damage to reputation. Far too many pounds.

This scenario has a name: technical debt.

Technical debt works like a loan that accelerates software development. But this loan is not free. Interest is due. And interest on the interest.

What would have been a ten-day project three years ago now takes three months.

Not because developers have become slower, but because the system has grown and become more complex. No one has cleaned up. No one has started paying the interest and paying off the debt. [1]

This is an article about the interest on technical debt and why it is worth dealing with it regularly.

Alarming figures from the present

Technical debt is not a marginal issue or an internal annoyance that can be remedied with a little goodwill. It affects organisations across the board. And the situation is more serious than many people believe.

A recent Capterra study [2] paints a picture that could hardly be bleaker. Only 29 percent of software buyers in Germany are satisfied with their decision. In other words, two-thirds invest time, budget and hope in a product that ultimately fails to deliver what it promises. Software is not procured or developed to make the day more exciting. It is done to solve a problem. What if all that remains afterwards is disillusionment? Ouch.

The extent of the problem becomes even clearer when you look at the causes. The biggest source of disappointment is not missing features, but disruptions during implementation and ongoing operation. As soon as things go wrong, 85 percent of affected buyers regret their purchase. A failure at the wrong moment, unstable performance, a process that stalls shortly after go-live: and suddenly the hoped-for progress turns into a step backwards.

The most common reasons for this disappointment read like a textbook on technical debt. Bugs. Crashes. Performance issues. Lack of reliability. Inadequate support. None of this happens overnight. All of it is the direct result of systems that have grown over years without quality, testing and maintainability growing consistently alongside them.

What is remarkable is what satisfied buyers do differently. They plan implementation and operation more consciously. They define requirements more clearly. They check security more thoroughly. They rely on real experience rather than marketing rhetoric. In short, they treat software not as a product to be implemented once, but as a responsibility that must be maintained.

These figures are not exceptions or a snapshot. They show a pattern. A pattern that is closely linked to technical debt and costs organisations dearly.

Why does technical debt arise?

Technical debt rarely arises because someone wants to write bad code. No one wakes up in the morning and thinks, ‘Today I’m going to build something that is guaranteed to cause problems in three years.’ And yet that is exactly what happens. Time and time again. In almost every company.

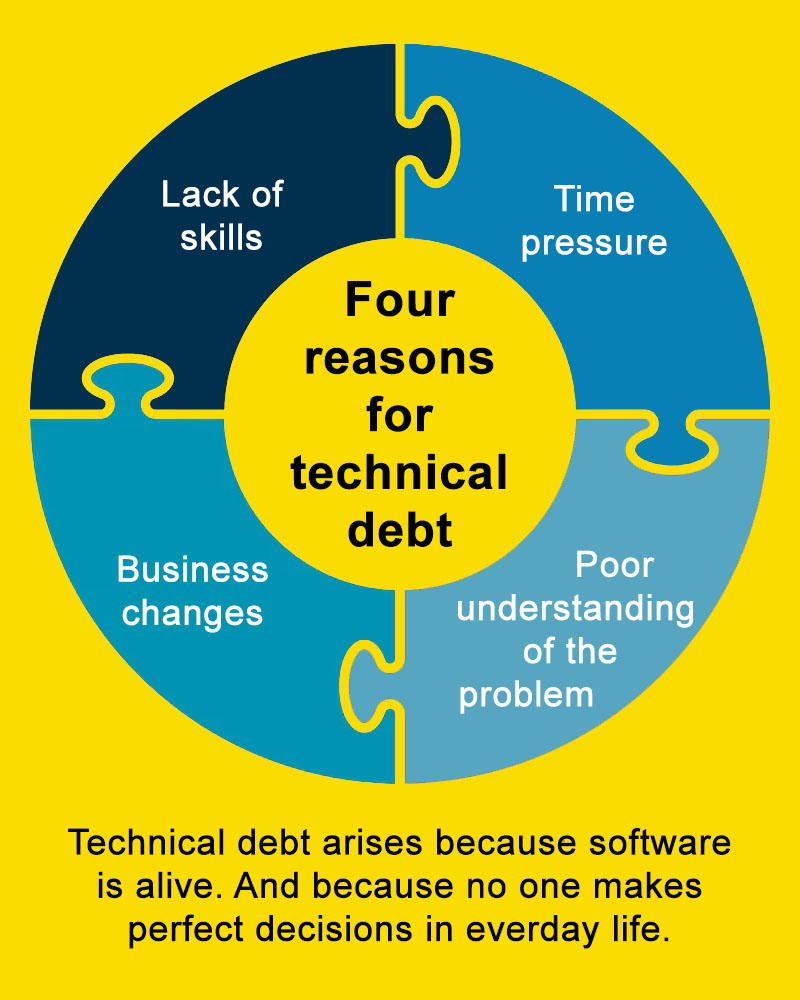

There are four key reasons that persistently run through almost all projects.

The first reason is obvious: a lack of skills in the team. If developers are unfamiliar with certain patterns, if architectural principles are unclear, or if important fundamentals are missing, you quickly end up with solutions that work in the short term but become expensive in the long term. However, this point only explains a small part of technical debt.

The second reason is much more common: time pressure. Deadlines, releases, promises to customers. In such situations, the fastest solution often wins out over the best one. Short-term shortcuts seem harmless, but the consequences will follow later. A patch here, a copy of a module there, an exception in the code that will need to be cleaned up later. But later rarely comes. And many small shortcuts result in a system that no one wants to touch without first taking a deep breath.

The third reason is more insidious: a lack of understanding of the actual problem. If it is unclear what a feature is needed for or how a process really works, a solution is built that works, but solves the wrong problem. This creates unnecessary complexity, makes adjustments difficult and makes systems harder to operate and scale.

The fourth reason is inevitable: business changes. Even well-developed software eventually becomes an obstacle when requirements grow, markets shift or new regulatory requirements come into force. An architecture that was perfect yesterday may reach its limits tomorrow because the company has become bigger, faster or more digital.

These four reasons lead to a realisation that many are reluctant to hear: technical debt is not caused by negligence, but by reality. By decisions made under uncertainty. By speed. By growth. By complexity. And by attempting to develop and operate simultaneously.

In short, technical debt arises because software is alive. And because no one makes perfect decisions in everyday life. So the question is not whether technical debt arises, but what to do with it afterwards.

Illustration: Four reasons for technical debt

Technical debt in the age of AI

Artificial intelligence is changing the way software is developed. It speeds up many processes, makes many things easier and opens up possibilities that were unthinkable just a few years ago. But this speed comes with a new risk: technical debt is accumulating faster than ever before.

Many teams are experiencing a paradoxical development. On the one hand, AI helps with writing code. It generates functions, suggests solutions and delivers results in minutes. On the other hand, this creates a new problem. Speed is no substitute for architecture. If code is generated without understanding aspects such as separation of concerns, security, scalability or testability, the result is not progress, but future effort.

The consequences can already be seen in the everyday life of many organisations. Prototypes are created at breakneck speed, appear promising and tempt us to put them into operation quickly. Often far too early. Code grows in breadth, but not in depth. Tests are missing, documentation is missing, structure is missing. AI makes it easy to generate a lot of software in a very short time. And just as easy to let interest grow at breakneck speed.

At the same time, a second opportunity is being overlooked. We overestimate how fast we can build with AI, and we underestimate how much better we could build with AI. Because the same tools that produce untested code today could help reduce technical debt. AI can generate tests [3], review architectural designs, identify security vulnerabilities, analyse code complexity, and reveal dependencies.

However, the greatest potential still lies ahead of us. In the future, AI could be used to refactor, document and modernise large systems in a targeted manner. It could enable developers to understand unknown systems immediately. And it could take on those tasks that currently take months and block entire teams.

But we are not there yet. At the moment, AI is primarily an amplifier. An amplifier of both good and bad decisions. Those who work cleanly achieve better results faster with AI. But those who work without an understanding of architecture generate debt at a rapid pace.

AI does not automatically make technical debt worse. But it increases the speed at which it accumulates. And it is precisely this acceleration that should be taken seriously. In a world where software is written faster than ever before, quality is even more decisive in determining whether a company will remain innovative in three years’ time or will have to pay the compound interest on its technical debt.

Why can’t technical debt be avoided?

Technical debt has a bad reputation. It is considered a mistake, negligence or a sign of poor discipline. But this view is too narrow. Technical debt cannot be completely avoided. Not in small projects, not in large systems and certainly not in organisations that are growing, changing and under time pressure.

The first reason for this is trivial but crucial: all software is alive. Requirements change, markets move, rules are adapted. An architecture that fits perfectly today can become an obstacle tomorrow. Not because it was poorly developed, but because the world has moved on.

The second reason lies in the everyday reality of product development. Projects never run under ideal conditions. Deadlines don’t shift, requirements are not always fully understood, and teams often have to deliver before everything has been finalised. Shortcuts, quick fixes and pragmatic decisions are inevitable. They help to build momentum, but inevitably create debt.

The third reason is strategic in nature. Some shortcuts are chosen deliberately. When a feature needs to be brought to market urgently or a regulatory deadline cannot be postponed, a conflict of objectives arises. The choice is not between quality and no quality. It is between delivering now or paying interest later. Anyone who uses a quick fix in such situations is not doing anything wrong. They are simply postponing the price.

The fourth reason is technological progress. New technologies, new frameworks and new infrastructures are emerging at a rapid pace. What was state of the art three years ago is now considered cumbersome. Systems age, even if the code is clean. The question is not whether they age. The question is whether you invest in time so that the software can cope with change.

Technical debt is therefore not the result of poor work, but the result of real decisions made under real conditions. It arises automatically as soon as software grows, as soon as companies grow, and as soon as there is more than one stable state.

The crucial thing is therefore not the illusion of being able to avoid it. The crucial thing is to make it visible, manage it consciously, and pay it off regularly. Those who do so are not working against technical debt, but with it. And that is the only way to remain agile in the long term.

How to deal with technical debt

If technical debt is unavoidable, the next question is: How can it be managed in such a way that systems remain stable, teams remain capable of acting, and companies do not eventually come to a complete standstill?

The first step is obvious, yet often overlooked: visibility. Technical debt does not disappear if you ignore it. It only becomes more expensive. Teams therefore need a common understanding of where the debt lies, how big it is and what consequences it has. This is not a cosmetic correction. It is risk management.

The second step concerns the rhythm of work. Those who continuously reduce debt remain flexible. Those who wait until there is no other option pay high interest rates. Fixed investment periods are needed for refactoring, testing, streamlining and modernisation. Not as an exception, but as a working principle. Teams that make room for this in every iteration do not waste time. They are investing in the future.

The third step is honesty when it comes to shortcuts. Sometimes there is no way around them. A market launch is pressing, a customer needs something immediately, or a regulatory requirement cannot be postponed. In such moments, technical debt is created consciously. But then the rule is: write it down, communicate openly, and clean it up immediately afterwards. Shortcuts are only dangerous if they are left in place as a permanent solution.

The fourth step concerns decisions at the system level. Much technical debt does not arise in the code of individual functions, but in the architecture. A few hours are not enough to solve problems there. It takes a clear vision of how the system should evolve and a technical roadmap that implements this vision step by step. Major improvements do not happen in a sprint, but they do happen when you weave them into every sprint.

The fifth step is collaboration. Technical debt does not only affect developers. Product management, operations, security and executives are responsible for how much space is given to quality. If value creation is defined exclusively by new features, pressure is automatically created that generates debt. If quality is part of value creation, space is created to reduce debt.

The sixth step is cultural in nature. Teams that improve software while working, rather than just using it, have an advantage. This includes simple rules, such as the requirement that any code you touch must be left in a better state than you found it. Small improvements add up. And they prevent a system from imperceptibly deteriorating over months.

Technical debt cannot be automated away. Even AI will only reduce the problem if people make decisions that allow for quality. The crucial difference between companies that grow with their systems and companies that fail because of them is therefore not in the code. It lies in the attitude.

Those who treat technical debt as an unavoidable companion but do not accept it as fate have a clear advantage. Because the price of consistent maintenance is manageable. The price of years of ignorance is not.

Conclusion

Technical debt is not an exception, but an inevitable side effect of living systems. It arises from time pressure, misplaced priorities, incomplete understanding of problems and the dynamics of business. AI further accelerates this development and can cause debt to grow faster than teams can control it. At the same time, it offers opportunities to strengthen quality, architecture and maintainability if used consciously.

The key is not to avoid technical debt, but to make it visible, manage it systematically and consciously pay its interest. Those who invest continuously remain capable of acting. Those who wait for years will eventually be faced with a system that can only be saved by expensive modernisation.

Do you remember the caller at the beginning of this article? He put the new feature on hold for the time being. Instead, he is now investing three months in modernising the system so that the next feature can be implemented safely in two weeks. That is the right decision, but it comes three years too late. Three years in which the interest on technical debt has quietly grown until no one could ignore it anymore.

What remains is a direct question: How long does it take to implement a simple feature in your system?

Notes (some in German):

[1] The story was written by Dennis Wilke and can be found in a LinkedIn post.

[2] Capterra study: Software Buying Trends 2026 – How to choose the right software: 5 success strategies from German companies

[3] Generating unit tests with AI – a field report on creating unit tests with ChatGPT, Claude and Gemini

By the way, the Software Engineering Institute at Carnegie Mellon University defines 13 types of technical debt.

Would you like to discuss the interest rates of technical debt as a multiplier or opinion leader? Then share this post in your networks.

Michael Schenkel has published more articles on the t2informatik Blog, including:

Michael Schenkel

Head of Marketing, t2informatik GmbH

Michael Schenkel has a heart for marketing - so it is fitting that he is responsible for marketing at t2informatik. He likes to blog, likes a change of perspective and tries to offer useful information - e.g. here in the blog - at a time when there is a lot of talk about people's decreasing attention span. If you feel like it, arrange to meet him for a coffee and a piece of cake; he will certainly look forward to it!

In the t2informatik Blog, we publish articles for people in organisations. For these people, we develop and modernise software. Pragmatic. ✔️ Personal. ✔️ Professional. ✔️ Click here to find out more.