From why questions to miracle questions

“Questions can taste like kisses” is the title of a wonderful book by Carmen Kindl-Beilfuß about systemic questioning.¹ And when they taste like that, they also bring a lot of insight, even on both sides. That is very helpful when you are in the process of solving a problem that makes emotions boil up.

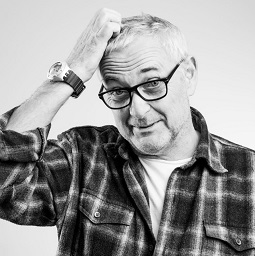

One person who also knows a lot about this is the somewhat quirky “oh-just-one-more-thing” TV inspector Columbo. Our advantage – we can look over his shoulder as he solves his problems. Every week again. What do we see? First of all, the familiar standards of open and closed questions.

Closed questions

Columbo usually asks closed questions along the lines of “Were you home by 9 p.m.?” or “Did you go to the restaurant before or after?”

Questions along the lines of “Yes or No / A or B” are good for confirming and specifying a fact. The parties involved can define their positions neatly or confirm facts and procedures precisely. Very good, we can also adopt this for our problem solving.

But – such a cascade of closed questions in connection with a “discussion of errors” can already produce a somewhat oppressive feeling. Besides this emotional disadvantage, closed questions also have an informational disadvantage: you don’t learn anything new. The questions remain within the realm of what is already known. A third disadvantage – if the other side doesn’t want to have a conversation, closed questions won’t produce one either. Question, answer, end. You have to start again and again, there is no flow to the conversation. The term “concluding questions” describes their influence on the course of the conversation much better.

Open questions

In order to learn something new, the questions must create free spaces, so the title “opening questions” would be more appropriate.

This brings us to the large group of W-questions. The first one that usually comes to mind – especially when spontaneously checking an unsatisfactorily completed task – is the why-question. “Why did you do it this way/not that way?” Please forget why-questions right away, because they often produce frustration and do not provide usable information. They target motive and easily come across as an attack demanding justification.

That is why we will never hear this question from Columbo; he finds out the motive in this way and he can well do without the indignation of his interlocutors. He likes to use some opening questions to clarify facts. They begin with “where, when, how, who…”. “. We can also use these questions to find out what actually happened:

- “Where did this take place?”

- “When did this thing start?”

- “How did it happen?”

- “Who else was on the team?”

However, whether we succeed in actually opening up a space for conversation with these questions depends on who uses them and how:

- Is there a power imbalance between the two sides? Eye level is helpful!

- Do the questions sound like accusations? Not good!

- Do they switch from the usual informal everyday language to formal formulations to emphasise importance? Also not good!

Columbo sometimes becomes more explicit when people can’t threaten him. Nobody is perfect! You should not adopt this if you intend to discuss something together. “Tell me, when did these faults actually start?” seems somehow more inviting than a stiff “When did the fault first occur?”.

A second group of opening questions sounds much more inspiring. Instead of reproducing events, it is about imaginations, wishes, ideas:

- “How would you have organised all this?”

- “What should we do differently next time?”

- “What do you think was the cause of the deviations?”

Reproach-free, solution-oriented formulations in acceptable language that encourage reflection. The conversation could lead to good insights. Columbo makes it sound like this: “Do you have any idea how someone could have got into the house unnoticed after you had switched on the alarm system?

Getting answers without asking

And Columbo goes one very interesting step further, which actually makes him a master of conversation. Instead of addressing someone specifically, he prefers to think out loud, dropping shards of thought that others pick up on and think on. He only half-formulates questions and his conversation partners complete them. To make this work, he plays with pauses.

To stay with our example:

- “I was just wondering when these disturbances actually started?”

- “Say, I was just wondering what we would have to change so that next time …”

- “You mean trouble-free?” “Yo!” “I think…”

Enough of Columbo.

Scaling questions

Scaling questions are a mixed form that first ask a fact and then lead into a very open discussion.

- “On a scale of 1-10, which value do you think best describes the quality of the project process?”

- “And what would have to happen, what would have to change for you to give a 10?”

The trick here is that it is easier for the gut to give a number than for the head to formulate it straight away with the appropriate explanation, taking into account countless contingencies. Once the number is given, it is easier to talk about the reasons, because the first hurdle has already been overcome. Incidentally, this works even better when the stomach doesn’t even have to say anything, but can simply make a cross or push a chip onto the right scale value. Our rational control authority doesn’t notice that, it only scans facts.

By the way, this is how Jurgen Appelo’s “Moving Motivators” work, and this is also a very good way to work with Delegation Poker, Planning Poker runs the same way for this reason. “First vote, then discuss” is what David Marquet called it in his recent book “Leadership is Language”²].

My perspective – your perspective

What all the question patterns discussed so far have in common is that they only deal with the interviewee’s view of the event and that too rather one-dimensionally: “I see it like this!”

Times are becoming more demanding, the influencing factors are increasing, the interdependencies are difficult to oversee, many things are interrelated.

The sender-receiver model is too short-sighted, because not only in human communication is every effect at the same time always the cause of a new re-action, when something started can become a series without end.

What we need are additional perspectives, change of perspective is the key to more insight. This leads us to a new class of opening questions, to a different way of asking.

Systemic questions

Systemic questions look at the events in their interdependencies and primarily aim to gain knowledge from the person being questioned. They are coaching questions. This can only be an advantage in a conflict resolution discussion. Let’s look at a few examples.

First, we clarify the frame in which the problem is situated, if possible from the point of view of other people.

The order frame

- Who had the idea for this meeting? How did the contact come about?

- Suppose this meeting was a success for you and you were very satisfied, who would notice this first and how would this person notice it?

- Suppose a colleague asks you about what you learned after the meeting, what will you tell?

The problem frame

- When does the problem show up? When does it not show?

- What must not be addressed in your company/team etc.?

- Who contributes to the success of the project etc.?

The solution frame

- What would be the first sign that something is changing?

- What do you think is the maximum we can achieve?

- What do you need to do to get one step closer to your goal?

Next, we dig out the problem together, again from different perspectives or with changed time horizons.

Concretising the problem

- What do you think your boss thinks you should do about the issue?

- What do you think will be different in 6 months if you solve the problem today?

- If you wanted to make the situation worse, what would you have to do?

Explanation of the problem

- How do you explain that sometimes the problem arises and sometimes it does not?

- How have you been able to make it this far under these circumstances?

- What would you have to do to get into a similar situation again?

Finally, we get the interviewee to look at their own actions through someone else’s eyes or to travel in time.

Circular questions

Now it’s not about what the interviewee thinks, but what they think others think or say, observe or experience. This becomes exciting.

- What would X say if you did/said this?

- How would an outside observer describe the situation?

- What do you think X will think about Y if you ask Y to …. to do/say?

Hypothetical questions

What if? Let’s play out a few situations. Simulate a different reality.

- What would happen if you did nothing now?

- Suppose we had met 4 weeks ago, what …?

- What would you do differently next time if you were in this situation again?

Miracle questions

Let’s say a miracle happens overnight and your problem is solved! You can’t think more light-heartedly than with the miracle question.

- How would you recognise in the morning that this miracle has happened?

- Who else but you would be the first to notice this miracle?

- How would your colleagues know without you saying a word to them about it?

You can now learn all these systemic questions by heart and pull them out of your sleeve when the opportunity arises. But you can also familiarise yourself with the principles behind them and derive them situationally.

Either way, have fun and let yourself be surprised by the answers and insights.

Notes (mostly in German):

[1] Carmen Kindl-Beilfuss, Fragen koennen wie Kuesse schmecken. Systemische Fragetechniken für Anfaenger und Fortgeschrittene. Carl-Auer Heidelberg 2008

[2] David Marquet, Leadership is Language, Portfolio Penguin 2020

Weitere Literatur:

Carmen Kindl-Beilfuss, Einladung ins Wunderland. Systemische Feedback- und Interventionstechniken. Carl-Auer Heidelberg 2012

Systemische Fragen / Übersicht / z.B.:

Die 8 wichtigsten systemischen Fragen

Systemische Fragen: 6 Varianten & 71 Beispielfragen, die Sie unbedingt in Ihrem Repertoire haben sollten

Conrad Giller has published other articles in the t2informatik Blog:

Conrad Giller

Conrad Giller has been working for about 30 years as a trainer, coach and consultant for almost all challenges of oral communication: conflict, team, leadership, storytelling, presenting, moderating, media, etc. He is happy to pass on his experience online and offline in workshops.