What is Loss Aversion?

Table of Contents: Definition – Foundations – Examples – Strategies for overcoming – Questions from the field – Notes

Smartpedia: Loss aversion is the tendency to put a higher value on losses than on gains of the same amount. People tend to avoid risking to minimise losing.

Loss aversion: why losses weigh more heavily than gains

Why do we find it so difficult to revise a decision once it has been made, even if it is demonstrably wrong? Why do we hold shares that are falling in value, but sell them too soon when they are rising? The answer lies in a deeply rooted psychological phenomenon: loss aversion.

Loss aversion is one of the most influential concepts in behavioural economics and describes the tendency to attach more weight to losses than to gains of the same size. People feel the pain of a loss more intensely than the joy of an equally large gain. This principle influences our behavior in economics, finance, politics and everyday life.

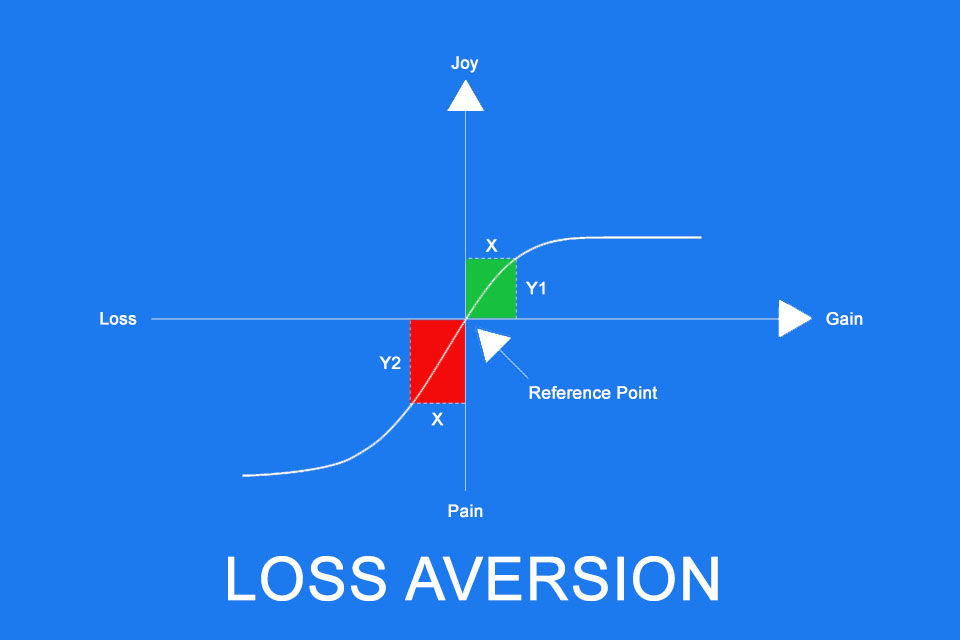

The term ‘loss aversion’ was first coined by psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in the context of prospect theory (1979). [1] They found that people in decision-making situations perceive uncertainty in terms of losses about 1.5 to 2.5 times more strongly than comparable gains.

Example: If someone wins 100 euros, they feel joy. However, the pain of losing 100 euros is much more intense. This distortion leads people to often make irrational decisions to avoid losses – even if it is harmful in the long term.

Psychological foundations of loss aversion

Loss aversion is deeply rooted in the psychological mechanisms of human thought and feeling. Our brain is not designed to evaluate gains and losses rationally and objectively. Instead, emotions, evolutionary adaptations and cognitive biases influence our decision-making.

Why our brain weighs losses more heavily than gains

Studies on the neurobiology of loss aversion show that the amygdala plays a central role in the processing of losses. In one study, Nicola Canessa and his colleagues were able to show that the amygdala is more active when processing losses, while the prefrontal cortex plays a more inhibitory role. This confirms earlier research findings on the role of the amygdala in decision-making under uncertainty. This reaction can lead to impulsive decisions to avoid losses as quickly as possible, even if this is not objectively the best choice.

At the same time, our prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for rational thought, is less involved when it comes to weighing up losses and gains. While rational decision-making would actually require a neutral assessment, the emotional reaction to losses leads people to act defensively, avoid risk or make irrational decisions. [3]

Evolutionary explanations of loss aversion

Loss aversion is not just a psychological phenomenon, but also has evolutionary roots. In the early days of humanity, the loss of resources, food or shelter could have serious consequences. Those who were able to avoid losses had an evolutionary advantage. This principle has developed over thousands of years and is still deeply rooted in our thinking today.

One example of this is how we deal with risks in nature. Our ancestors who were more cautious and focused on preserving resources had a better chance of survival than those who constantly took risks. This principle is reflected in economic and everyday decisions today: people are more willing to accept a small, secure profit than to take a greater risk for a larger reward. At the same time, they tend to make risky decisions when it comes to avoiding losses – even if that decision could be harmful in the long term. [4]

Social dynamics of loss aversion

Loss aversion not only affects individual decisions, but also influences our behavior in social contexts. Studies show that people are particularly sensitive to the loss of social status. The loss of social recognition can be perceived as similarly painful as a financial loss, which is reflected in neurobiological reactions. [5]

In early societies, the loss of status or resources could be life-threatening. Those who lost their reputation in a group could have a lower chance of survival, since cooperation and mutual support were essential for survival. These evolutionary mechanisms are still anchored in our behavior today and influence decisions in areas such as hierarchies in the workplace, social networks and economic cooperation.

Examples of loss aversion

Loss aversion occurs in various areas of life and influences numerous decisions. Here is a small selection of examples from the areas of software development, corporate strategy, professional life and career, social relationships, politics and society:

- A company is already investing considerable sums in a software project that is not yielding the desired results. Despite clear indications that it would make more sense to abort and restart, management is sticking with the project in order to avoid ‘losing’ the investments already made. This phenomenon is also known as the sunk cost fallacy.

- A company is using outdated software that is not compatible with modern technologies. The switch to a new platform is repeatedly postponed because the previous investments are seen as ‘lost’.

- A company is faced with the choice of purchasing a cost-effective but modern solution or a familiar but overpriced software. Often, the choice falls on the overpriced option because of previous experiences with the provider and because uncertainty is perceived as a ‘possible loss’.

- A large company has the opportunity to invest in an innovative but risky technology that promises high profits in the long term. However, instead of focusing on the opportunity, the fear of a possible loss of the investment prevails. Instead, management opts for a safer but less profitable alternative in order to avoid any financial risk. This results in competitors who take the risk achieving a long-term market advantage.

- Investors tend to hold stocks that are losing money for too long in the hope that the price will recover, rather than cutting their losses early (disposition effect).

- A long-standing employee of a company finds his work frustrating and sees little opportunity for development. Nevertheless, he holds on to his position because he has already invested many years in the company. The idea of making a fresh start and applying for a job elsewhere seems risky to him, as he fears that his efforts to date could be in vain. The fear of losing the time invested and the established routines prevents him from choosing a better alternative.

- An employee who has been with the same company for several years knows that his salary is no longer competitive. He would like to discuss a raise, but the fear of being seen as greedy or disloyal by his manager keeps him from doing so. Instead of focusing on the possibility of higher earnings, the concern of losing face or even his job due to a negative reaction from his boss prevails. So he remains underpaid in his position, even though objectively he has little to lose.

- An employee does not feel comfortable in his team because the working atmosphere is characterised by competition and unfair treatment. Nevertheless, he stays in the group because he fears that changing to another team could be seen as an admission of weakness. He also fears losing his existing networks and the status he has achieved in the group.

- A couple has been in a conflict-ridden relationship for years. Although both recognise that they are unhappy, they do not separate. The many years spent together, the emotional investments and the shared memories create the feeling that a separation would make all these efforts worthless. The fear of this loss outweighs the prospect of a happier future.

- A government recognises that comprehensive pension reform is necessary to ensure financial stability in the long term. Nevertheless, it delays implementation because of the negative reactions and possible loss of approval in the short term. Fear of losing votes causes urgently needed measures to be postponed or avoided altogether.

- A political party in an election campaign makes far-reaching promises to its voters, although it knows that these are financially or structurally difficult to implement. Nevertheless, it sticks to these promises because it fears that abandoning them could cost it voters. After the elections, she faces the dilemma of either breaking the unrealistic promises or implementing expensive, inefficient measures just to maintain the appearance of continuity and credibility. Nevertheless, implementation is delayed because of the short-term negative reactions and possibly falling approval ratings.

These examples show that loss aversion is a ubiquitous phenomenon that occurs in almost all areas of life. Whether in economic decisions, at work, in social relationships or in politics, the fear of loss often influences our actions more than the prospect of possible gains.

Strategies for overcoming loss aversion

Loss aversion is deeply rooted in our psyche and has evolutionary and social causes. While it used to be a survival advantage, in the modern world it can lead to irrational decisions. However, there are ways to counteract this behavior. With conscious techniques, rational decisions can be made that are not distorted by excessive fear of loss.

Awareness and cognitive techniques

The first step in overcoming loss aversion is to recognise that this psychological phenomenon is affecting your thinking. A helpful approach is to reflect on decisions in a calm environment and ask yourself: would I make the same decision if I hadn’t already invested time, money or emotions?

A proven technique is so-called ‘mental accounting’, in which you imagine that the previous investment is irrelevant and you would have to make the decision again. This technique helps to reduce emotional ties and focus on objective factors.

Another effective method is reframing, a proven technique from psychology. This involves looking at a situation from a new perspective in order to reduce the emotional reaction to losses. For example, selling an unprofitable investment can be viewed not as a failure, but as a strategic adjustment. This change of perspective can minimise irrational fears and promote rational decision-making. – You imagine how a decision could play out in the long term and how big a short-term loss really is. By consciously weighing things up rationally, emotional distortions can be reduced.

A proven approach to reducing loss aversion is ‘cognitive behavioural therapy’ (CBT). This method helps to question irrational fears of loss and replace them with realistic assessments. In a typical CBT exercise, a person who is afraid of selling a losing investment might make a list of logical arguments for and against holding on to that investment. This conscious juxtaposition makes it clear that emotional fears are often overstated.

Another method is ‘exponential thinking’, which helps to visualise the long-term consequences of decisions. For example, a person who is afraid of a career change can look at the possible development over a ten-year period. By visualising the positive long-term consequences of a courageous decision, it becomes clear that a short-term loss is often only an intermediate step on the road to long-term success. It helps to question irrational fears of loss and replace them with realistic assessments.

Practical tips

The following tips can help to minimise loss aversion in various areas of life. It is important to be aware of how strongly fear of loss influences decisions in order to take targeted countermeasures and make more rational decisions.

- Decisions are easier to make when they are based on long-term goals rather than determined by short-term fear of loss. Therefore, set yourself clear goals.

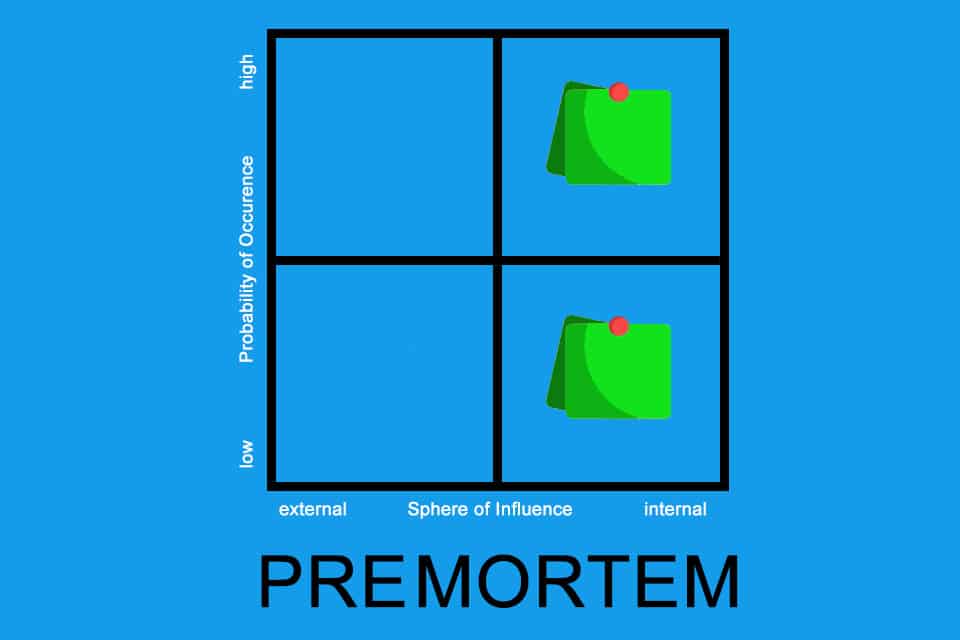

- Imagine a decision going wrong and analyse the possible reasons. This pre-mortem technique enables you to recognise possible weak points early on and to react more consciously to possible problems. Irrational fears can often be dispelled in this way.

- You can learn from every mistake. If you see losses not as a final failure but as a learning process, you can use them constructively and gain valuable experience from them.

- Wait to make important decisions until you are emotionally stable. Loss aversion is particularly strong when emotions are involved. Rational deliberation is much easier in a calm state.

- Try to look at your decision from a distance. Ask yourself what you would advise another person in a similar situation to avoid emotional distortions.

- Base your decisions on probabilities and long-term effects rather than absolute certainty. This reduces the fear of losses and promotes a realistic assessment of opportunities.

- Set clear rules for your decisions to avoid impulsive behaviour. For example, a set sales target can help to minimise emotional mistakes on the stock market. Clear rules prevent emotional mistakes.

- If you are afraid of big changes, start with small steps. For example, a career change can be tested by taking a part-time job before making a final decision.

These tips show that loss aversion can be overcome by approaching decisions consciously, reflectively and in a structured way. Anyone who regularly engages with these techniques can learn to make better and more rational decisions in the long term.

Questions from the field

Here are some questions and answers from the field:

How can I recognise whether loss aversion is influencing my decisions?

Many people are unaware that their decision-making processes are distorted by loss aversion. A clear sign is when you find it difficult to accept past investments (be it time, money or energy) as ‘lost costs’. Ask yourself the following questions: Would I make the same decision if I started over today? Am I more afraid of a loss than of a possible gain? If so, it is likely that loss aversion is playing a role.

Why is it so hard to let go of investments?

People often cling to decisions because they have already invested in them, whether in old projects, unused subscriptions or failed business strategies. This phenomenon is exacerbated by the emotional attachment to investments that have already been made. One way to break free from this is to focus on future costs and benefits rather than looking back at past investments. Ask yourself: ‘Would I choose this project or investment again?’

How can I make decisions without being guided by fears of loss?

Loss aversion increases under stress because the brain tends to react impulsively and risk-averse in uncertain moments. One effective method is to establish a decision-making process: define criteria according to which you want to make decisions, and set clear limits, e.g. when you want to stop an investment or seek a career change. It can also be helpful to take a neutral perspective, for example by imagining that you are explaining the situation to a friend and that person is giving you advice.

Those who use these techniques regularly can learn to make better and more rational decisions in the long term.

Impulse to discuss:

How can loss aversion be made visible in your organisation?

Notes:

[1] Daniel Kahnemann and Amos Tversky: Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk

[2] Nicola Cassena et al.: The functional and structural neural basis of individual differences in loss aversion

[3] Benedetto De Martino et al.: Frames, Biases, and Rational Decision-Making in the Human Brain

[4] E. Yechiam & C. Hochman: Loss-aversion or loss-attention: The impact of losses on cognitive performance

[5] Christoph W. Korn et al.: Positively Biased Processing of Self-Relevant Social Feedback

The graph shows a value asymmetry in which the expected negative utility (Y2) of a loss is experienced more intensely than the expected positive utility (Y1) of a gain of the same absolute size X. The value asymmetry results from the shape of the value function, which is convex in the loss area and concave in the gain area. In Prospect Theory, losses and gains are not presented as absolute values, but as changes relative to a reference point.

Here you will find additional information from our Smartpedia section: