Cultural Hacking. A contribution to culture change?

This is how we do things around here!

“Culture eats strategy for breakfast”. This statement is attributed to Peter Drucker, but no source can actually be found for it. Drucker may have said or written something similar, but more importantly, Drucker may have said or written it. We tend to put wise sayings into the mouths of wise people. In any case, the statement expresses the fact that corporate culture is more important than a sophisticated strategy.

Corporate culture is formed – and here the source can be identified – along the so-called “basic assumptions”: “A pattern of basic assumptions – invented, discovered or developed by a given group as it learns to deal with the problems of external adaptation and internal integration – that work well enough to be regarded (by that group) as valid, and which are therefore transmitted to new members as the proper way of perceiving, thinking and feeling about those problems”.1 Other authors summarise corporate culture even more simply: “This is how we do things around here”.2

This is how we do things around here! I think each of us has become sufficiently well acquainted with the explicit, but above all also the secret rules of the game in companies. Culture determines how selections and socialisations take place in companies and how problems are solved. It is the “soft stuff”, it is the “soft facts” that have a decisive influence on the tangible in the intangible. And that is why, when companies want to or have to change, the topic of cultural change inevitably comes into play.

Cultural change as a mechanism for better results

The connection seems obvious: cultural values and norms shape behaviour and behaviour influences results. This is why studies postulate that “strong” corporate cultures have an above-average positive effect on growth and operating results.3 The question of how to distinguish “strong” from “weak” cultures leaves me a little perplexed, but I cannot completely escape the correlation suggested in this way. In any case, this alleged correlation has for several decades brought managers, consultants and trainers onto the stage who want to change corporate cultures in order to create the basis for improved results. And quite a few of these cultural change programmes follow a top-down and/or campaign logic, with which a “target culture” is to be defined and the “actual culture” is to be changed through values, mission statements, etc. So far, so mechanistic. Against this background, it is no wonder that a little disillusionment has set in with regard to culture change programmes.4

Social systems are complex systems and they don’t change simply by an announcement or a great mission statement. The following picture is a good example of how words are one thing, but action is the other:

I think all of us know the meaningless appeals that fizzle out ineffectively even when it comes to self-evident things like not simply throwing the rubbish next to the dustbin. The injunctive norm of cultural action (“rubbish belongs in the bin”) is dominated by the descriptive norm (“everyone does that anyway when the bin is full”) and there is no meaningful consistency of behaviour to the appeal.

Hacking in social systems

And this is where a new term now comes in, that of “cultural hack”, which I first read by Scheller5. Curious, I came across an interesting publication edited by Duello and Liebl6. In the anthology, which brings together various authors and examples from quite different disciplines (politics, German studies, art, advertising, etc.), it becomes clear quite quickly that it is perhaps rather minor irritations that can initially challenge a culture and subsequently also change it. The term “hack” does not come from the computer scene, as I had wrongly assumed, but from journalism: “A hack was originally an expression for journalistic work with unorthodox means”7 and only then found its way into IT. “Hacking is a form of exploring and manipulating that not only learns how a specific system behaves but also discovers how to employ its tools and procedures against and in excess of the necessary limitations of its own programming”.8

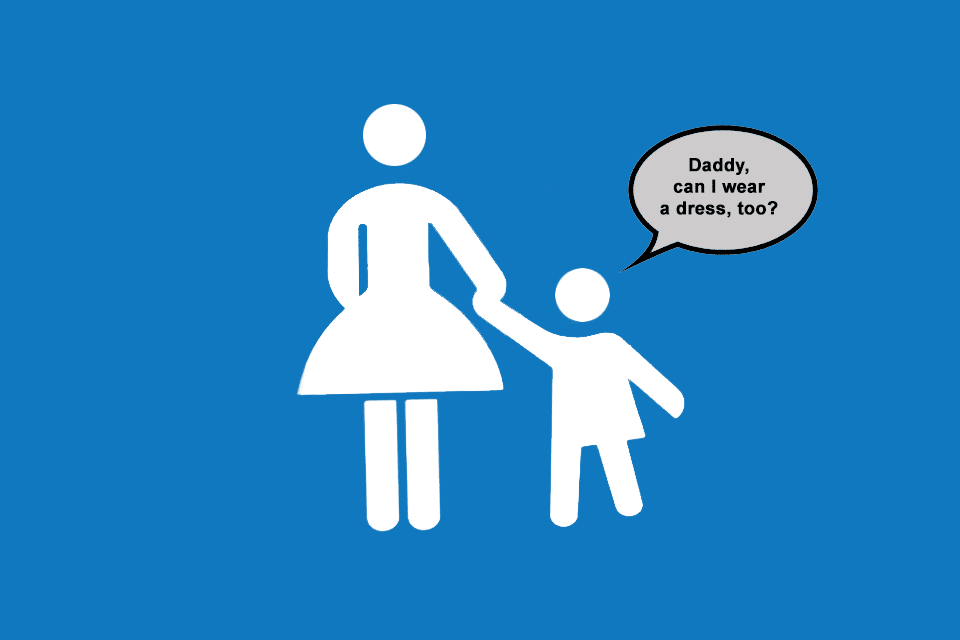

So it is the hackers who penetrate a system, learn about it and find ways to recode it. In doing so, they proceed iteratively, by trial and error, and create experimental arrangements for a small but calculated and precise intervention into the system. In each case, this makes the established, often invisible patterns of interpretation visible and sometimes downright ridiculous. The system is now confronted with its own concrete patterns and thus challenged. And this irritating impulse can then potentially have more effect than the umpteenth top-down announcement. Here, too, an image shows how simple and at the same time well-calculated a cultural hack can be in which gender roles are confronted:9

- There are only two genders.

- Each of the two sexes needs a separate room for going to the toilet.

- The icons show the stereotypical ideas of “male” and “female”.

With a few simple steps, a cultural hack can be carried out here that confronts us with our assumptions very effectively:10

I think this should make it clear what a cultural hack can achieve and where its limits lie. But what does this mean for the corporate context?

Cultural hacking in the corporate context

As with computer hacking, cultural hacking in the corporate context means changing the “software”, i.e. our cultural assumptions, from the inside out. And it is not the entire social system that is targeted, but “only” one, and in this case usually a “weak” and thus easily attackable part of the social system. The aim is no longer to change “the culture” as a whole, but to change individual, or even small, parts of the cultural assumptions. Here – and this is also a serious difference from the cultural changes practised so far – the system is stimulated to change and act differently through concrete actions (!) and not through appeals. A much more modest claim, but one that also does better justice to the complexity and inherent stability of social systems.

Solid preparation of the hacks is important here, but at the same time it is not witchcraft. First of all, it is crucial that there are no over-optimistic and overly concrete expectations of results and certainly no promises that cannot be kept for the umpteenth time. Then, in a small circle – preferably cross-functional and cross-hierarchical – work should be done on topics where there is the “greatest desire” for change or a “real pain” in everyday life. In principle, it should be possible to address any topic, there should be no taboos and no “sacred cows”. Finally, it is important to work in one’s own “Circle of Influence”, i.e. where an effective implementation of the hack can take place immediately in the next hour, the next day. Nevertheless, hacks always remain experiments, there is no guarantee of success for effective change.

Cultural hacking example

An example? In one company, a hacking workshop resulted in the following problem description:

“Almost all meetings start too late, with an incomplete group of participants. As a result, we start the meeting over and over again and waste time. During the meeting there is a ‘coming and going’ and the meetings end before the agreed time because most of the participants have to leave earlier. The meeting result is therefore not actually shared by all and leads to further coordination loops later on. In principle, this happens in all meetings, in all functions and at all hierarchical levels. It is worst in cross-functional and cross-hierarchical meetings.”

And this despite the fact that rules for precisely this point are posted in every meeting room (as in the “Parkplatz sauber halten” / “keep the car park clean” example above), there are always appeals for attention and ultimately everyone considers the injunctive norm (“be on time”) worthy of attention. So what to do? The workshop participants, which included one of the directors, agreed, each in his or her circle of influence:

“With the official start of the meeting, the door is locked from the inside. Anyone who is not on time stays outside. If we do this especially in meetings by and with the executive board, the sign will go through the organisation really fast and the attention for our unproductive meeting culture will be really big.”

Ultimately, a Bible quote has already taught us this: “Not by their words, but by their deeds shall you recognise them!” (1 John 2:1-6)

Notes (partly in German):

[1] Edgar H. Schein: Organizational Culture and Leadership. A Dynamic View, San Francisco etc. 1985, S. 9

[2] D. Bright / B. Parkin: Human Resource Management – Concepts and Practices, 1997, S. 13

[3] see e.g. Why companies should look at culture’s impact on profit

[4] see. Kotter, Leading Change – Why Tranformation Efforts Fail or Martin Smith, Changing an organisation’s culture: Correlates of success and failure. Leadership & Organization Development Journal. 24. 249-261.

[5] see Scheller, Culture Hacking – Knacken Sie die Unternehmenskultur!

[6] Cultural Hacking. Kunst des strategischen Handelns, Wien 2005

[7] Duello / Liebl, Cultural Hacking – Kunst des Strategischen Handelns, S. 13

[8] Gunkel, Hacking Cyberspace, Boulder 2011, S. 6

[9] and [10] see https://kulturshaker.de/cultural-hacking/

Dr. Jürgen Schüppel has published another article in the t2informatik blog:

Dr. Jürgen Schüppel

Dr. Jürgen Schüppel studied business administration and organisational psychology in Munich and completed his doctoral studies in St. Gallen. After working as head of the management development department at the Institute of Business Administration at the University of St. Gallen and as a trainer and consultant for a management consultancy, he took over a professorship in business administration in 1997 and founded the change factory together with partners, a consulting and training company of which he is still managing partner today. His main areas of work include the support of change management projects as well as the conception and implementation of leadership development programs.