What agility and health have to do with each other

No one is immune: the waste of effective approaches

4 examples of effective approaches that are probably also gathering dust in your drawers

Spoiler: Agility could help you achieve better health

No, this is not another part of my series “Agility? We’ve tried it! Doesn’t work!”. And yet, I admit it, of course this article again has something to do with agility.

This time I would like to try to open one or two eyes for you. Because in the last few weeks – with a little distance, in my workatical – it has become clear to me that it is apparently not so easy to think about agility without blinkers and to use helpful approaches (e.g. retrospectives) outside their traditional pigeonholes.

In this article, I will use four concrete examples to explain how (agile) principles and practices can also be effective outside the familiar context – and in the fourth example, it’s down to the wire, it’s about your health!

But first a few introductory and classifying words:

Waste

Most organisations that bring in consultants or “agile coaches” like me want to change something, want to become “better” in a certain context or get problems solved. And perhaps it is deeply rooted in human nature that we tend to see the problems and difficulties rather than the things that are already going really well. But if we are honest: Some things must already be going really well (or at least have gone well at some point), otherwise the company wouldn’t even exist (any more).

My hypothesis is that there are good practices in every organisation that can be transferred to other contexts.

“The most dangerous kind of waste is the waste we do not recognise.” – Shigeo Shingo

And I think it is indeed a waste when we have learned and understood effective approaches, even applied them successfully, and then let them gather dust in their drawers instead of using them in other contexts.

Often we don’t even notice this.

Perhaps this is a special form of operational blindness?

How about thinking “out of the box” – in this case, it’s not about blatant, disruptive innovations, but rather the opposite: in my opinion, we should look much more often at what is already there and works really well. The “edge of the plate” or the boundaries of the “box” of our thinking are much closer or narrower than we assume. Instead of being inspired by distant role models and utopian models, it is sometimes enough to rummage around in our own dusty drawers.

Of course, I am aware that you cannot simply transfer any practice that works very well in a very specific context to any other context and assume that it will work just as well there!

But as I said, I think that often enough it is not even thought about, let alone tried – so valuable potentials are wasted, including for our health!

I would now like to give a few examples from my own experience:

Example: Retrospectives

In many companies, regular retrospectives are now a lived and accepted part of the agile process, especially when Scrum is in use. (Some exceptions prove the rule.) Let’s assume that in most of these companies even the purpose of regular retrospectives in teams is understood:

- Continuous improvement,

- inspection & adaptation,

- constant adjustment of working methods to changes and

- new insights.

Most companies do not consist exclusively of agile teams developing products. There are usually also other working groups that work together on issues over a long period of time, although perhaps not at 100% of their respective capacity. There are often committees that meet regularly or come together for specific events. And there are often jour fixes and other meetings outside of Scrum that happen more than once.

And – surprise, surprise – not everything always goes smoothly in these cases either: participants have different expectations, people talk past each other, results are interpreted and communicated differently, some participants wonder what they are actually supposed to do there and what the point of the meeting is in the first place.

Sometimes I am asked for advice in such cases, sometimes I just overhear the frustration during a conversation in the coffee kitchen. And then I like to ask: When did you do the last retrospective?

Usually I can read the massive confusion and helplessness directly in their faces: Retrospective? But that’s what Scrum teams do, isn’t it? What does that have to do with my topic now? … and then at some point: Hm … right, maybe not such a bad idea….

What happened here? Retrospectives are nowadays so closely associated in many people’s minds with Scrum, i.e. with agile teams and product development, that we often find it difficult to free this practice from the Scrum drawer and apply it to other contexts.

By the way, Norman Kerth did not originally describe the retrospective for Scrum sprints but for projects – as far as I know, the integration into the Scrum framework came later.

In my experience, the (re)transfer of the practice “retrospective” into another context is really not rocket science. However, a few aspects should be considered, which I would only like to briefly outline here:

- Frequency and duration should be oriented to the duration and frequency of the object under consideration (e.g. rule meeting, committee).

- The less intensive the cooperation, the less in-depth I would expect the topics to be.

- Someone should take care that the retrospective takes place and is moderated – more on this in a moment.

Example: Moderation

Speaking of which: I’ll stay briefly on the topic of “meetings” and “committees”. In many companies, the role of Scrum Master for agile teams (sometimes it is also called “Agility Master” or similar terms are used if the teams are not organised exclusively according to Scrum) is now a lived and accepted component.

Unlike retrospectives, however, I don’t go so far as to say that the purpose and accountability is understood by most companies. But that should not be the topic here.

After all, I experience in most companies that the moderation of “meetings” by Scrum Masters is considered useful.

If moderation of meetings seems to be a good idea even for teams that work together 100% of their working time and thus have good prerequisites to become a “well-rehearsed team”, why do many organisations not come up with the idea that dedicated moderation could be all the more worthwhile for committees (steering board, management circle, …) that meet rather infrequently and thus can rather rarely be described as a “well-rehearsed team”? Especially since such “meetings” with many top-class executives are usually expensive, if one would dare to add up the hourly rates once…

Example: Business Model Canvas

Apropos: I hardly know a company where people don’t moan about the many and sometimes unnecessary or at least pointlessly long meetings. Somewhere I once read that people in so-called “middle management” spend up to 80% of their working time in meetings. And apparently this state of affairs is rarely perceived as optimal.

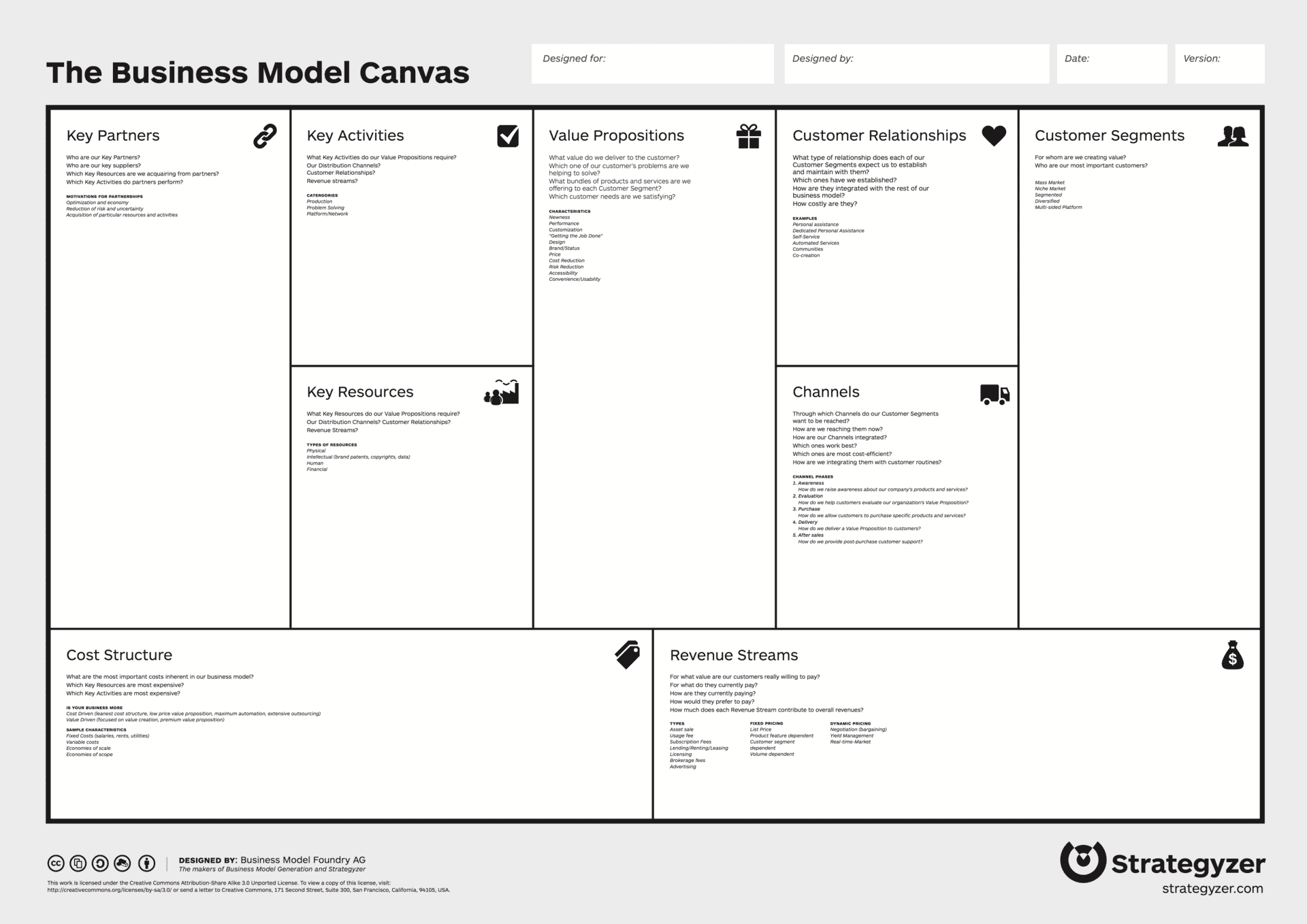

Sometimes I allow myself the following irritation: I ask for the Business Model Canvas of the meeting. You can certainly imagine the mimic reaction.

In my experience, the Business Model Canvas is a great tool for presenting the most important and critical aspects of a product or service “at a glance”. This creates a common view and you can talk about it, better than a business plan with tens of pages.

And isn’t a meeting or a committee also a kind of (internal) service?

- Shouldn’t it also be clear for each meeting for whom it is being done, who the beneficiaries or clients of the meeting are?

- Wouldn’t it make sense to think about the ideal channels for communicating with the beneficiaries of the meeting and what kind of relationship you want to have with them?

- Shouldn’t every meeting also have a clear benefit for the respective clients, i.e. a clear value proposition?

- Wouldn’t it be useful to derive from the value proposition what you have to do concretely to achieve this (topics, agenda, organisation), who you need for this and who you don’t, or in which role?

- And maybe it would even be interesting to compare the costs (imputed hourly rates of the participants or the opportunity costs) with the imputed income (benefits)?

Pro-tip: And if you were to put the canvas of all committees and meetings side by side, you would definitely notice one or two overlaps just by “rhythmically looking”, which you could easily do without and thus gain free capacities. (At least for a short time, because Parkinson’s Law still applies, of course).

Example: Agility and health

As already indicated in the last examples, I have the impression that agile procedures are now at least an accepted approach in many companies in order to be able to operate successfully under complexity and dynamics. Regular reviews and retrospectives (see above) are practices in the Scrum framework, among others, to force oneself again and again to check empirically – ideally on the basis of real data – whether one is still on the road to success or whether it might be better to correct the course. Continuous improvement and adaptation to changes can only succeed through regular inspection and adaptation.

Whereby one has to distinguish between aspiration and reality: I rarely meet people who claim that flying blind is the better option. But to be honest, I also hardly know teams that really consistently and continuously collect data and critically review or redefine their assumptions and decisions on this basis. It can also hurt when the numbers don’t match your own ideas.

In the previous example, I asked whether regular meetings and committees could not be considered (internal) products or services. If this is the case, then it might be easier to transfer tried and tested approaches from product development.

Now I’ll go a step further and come to my current topic of heart: health!

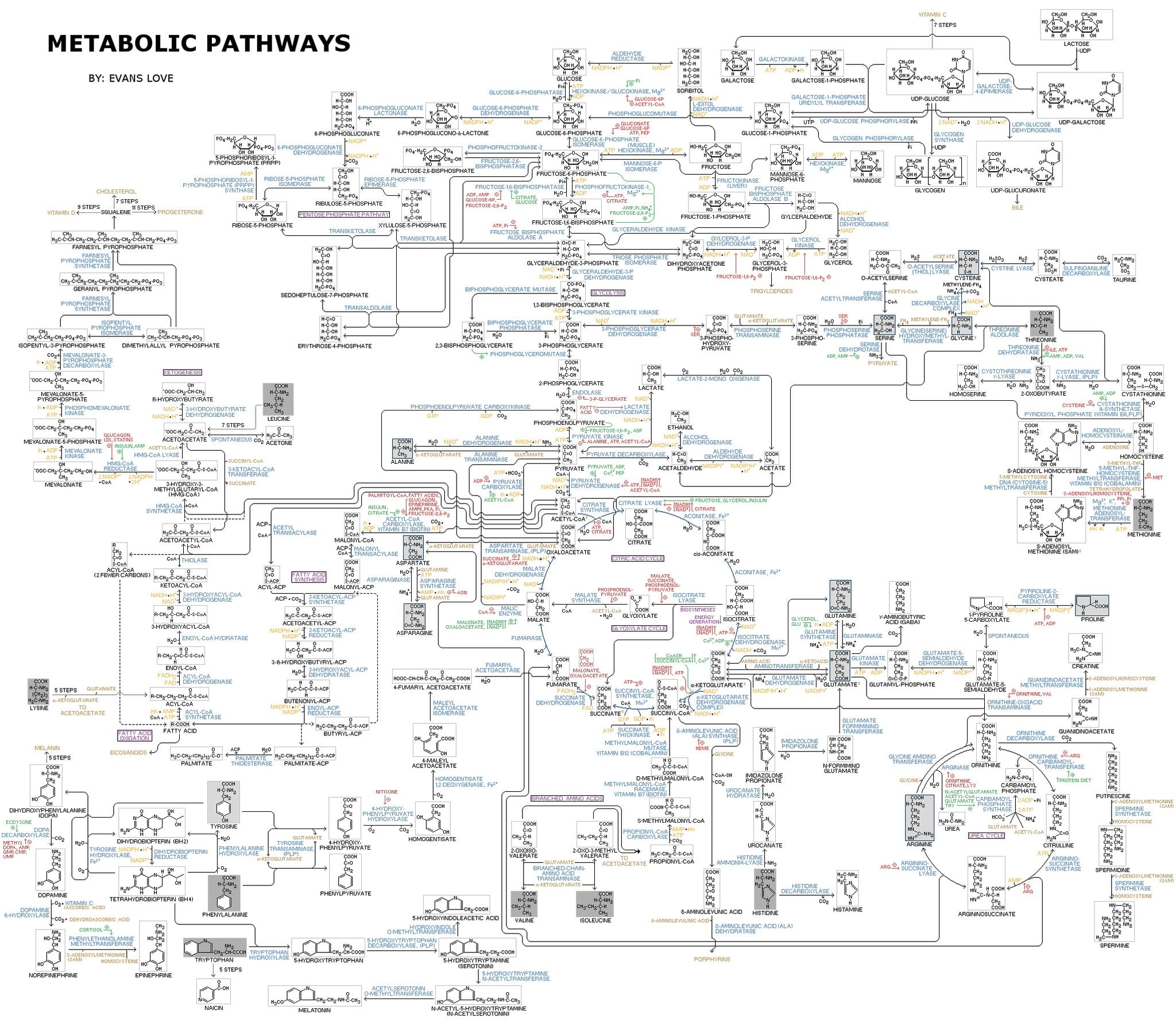

Isn’t our body and metabolism also a complicated and (at least due to environmental influences and the active participation of the microbiomes in the intestines, on the skin, in the mouth, etc.) highly complex system in which many things are interrelated and we can therefore never predict a priori what exactly will happen when something changes – comparable to, if not even more complex than, a social system like a company?

When I look at my health as a product or service in this complex context, I ask myself why the basic agile principle of empiricism is not also applied to our health?

Wouldn’t it also be a good idea for our own health to continuously measure empirically whether the body has everything it needs to deal with disturbances (e.g. viral infections, stressful project situations, etc.) and perhaps even to be able to perform at its best?

In a car, we always keep an eye on the fuel gauge (or the battery level), we regularly check the oil level and the level of the windscreen wiper system. With essential micronutrients, we only react – if at all – when something has broken down because important building blocks were missing.

I know (at least) three people personally who could most likely have avoided bone fractures (fatigue fractures or osteoporosis) if they had known their vitamin D level and increased it accordingly or kept it high.

What is stopping us from taking more responsibility for our own health (both as customers/beneficiaries and as providers/developers) instead of relying completely on our luck, the health system and doctors?

After all, many already use the readings that current smartwatches and other wearables offer us. From my point of view, these are helpful early warning systems that indicate symptoms, ideally before I feel it painfully.

But why don’t we go one step further to the causes? Why don’t we have all those values measured that are essential for our health and then use this as a basis to adjust our supplies (i.e. in particular our diet, and if necessary also targeted supplements) in such a way that any deficits are compensated for promptly. So why don’t we apply the Theory of Constraints, which has proven itself in production as well as in projects, to our metabolism?

And since it is a complex system and our lives are constantly changing, we regularly check whether the deficits have been compensated and whether new deficits have arisen. Based on real data, we regularly adjust our diet and targeted supplementation, while ensuring that we don’t overshoot and perhaps even supplement too much of a good thing. So why don’t we apply success-proven agile principles like empirically inspecting and adjusting to perhaps the most important product of all, our health?

How do you see it?

Open call

I am sure: there are many more valuable principles and effective practices gathering dust in drawers that are far too small.

What other pearls can you think of?

And if you feel like it, feel free to ask me to join you on an internal truffle hunt: together we will find good practices that are already successfully used and accepted. We identify further contexts in which they could be helpful and outline concrete experiments to test our assumptions in practice, empirically of course. This will not be an easy undertaking in all cases. But I am convinced: it is worth it!

In this sense: stay agile, stay curious, stay healthy!

Notes:

Here you can find the first parts of the series Agility? We have tried it! Doesn’t work!

Heiko Bartlog

Heiko Bartlog has more than 25 years of experience in projects, as a consultant, trainer, coach and entrepreneur, covering many different areas. As a ‘host for co-creation’, he supports organisations on their path to good cooperation and successful development. His repertoire includes approaches such as Scrum, Effectuation, Lean Startup, Management 3.0 and Liberating Structures. As a ‘mentor for mental fitness and vitality,’ he supports leaders in unlocking their potential.