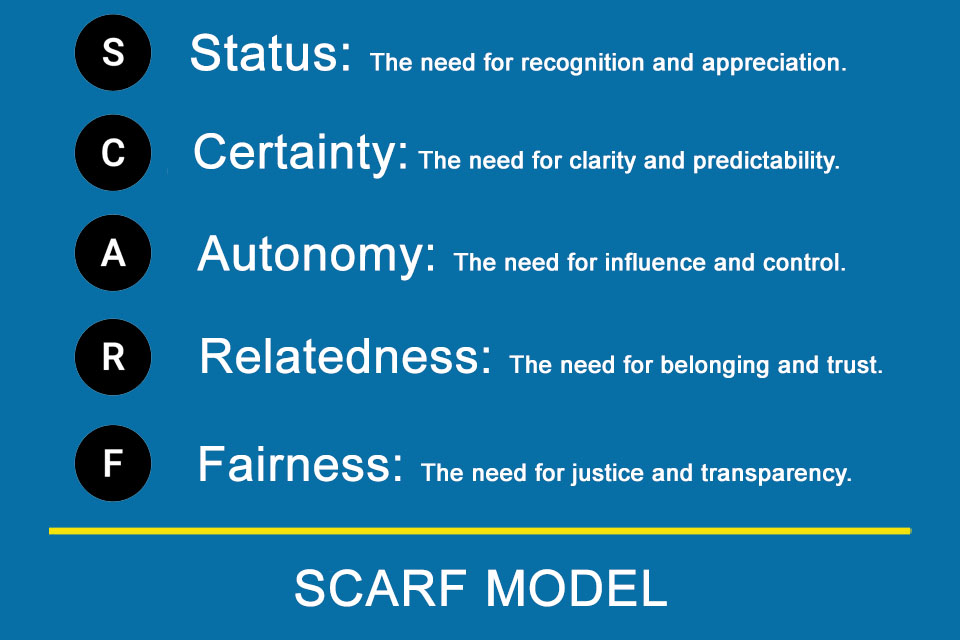

What is the SCARF Model?

Smartpedia: The SCARF Model describes five social needs (status, certainty, autonomy, relatedness, fairness) that shape behaviour in the work environment.

SCARF model – the effect of different basic needs

Sometimes a careless decision or a harmless comment is enough to cause employees to withdraw, resist or become frustrated. What at first glance appears irrational can often be explained by the fact that fundamental social needs have been violated unconsciously.

The SCARF model, developed in 2008 by neuroscientist and coach David Rock, offers a scientifically sound framework for better understanding precisely these reactions. [1] It describes five central social needs that strongly influence our behavior in social contexts, especially in the workplace: Status, Certainty, Autonomy, Relatedness, and Fairness.

SCARF model – the basic social needs in detail

The SCARF model describes five social needs – also referred to as dimensions in some articles – that significantly influence our thoughts, feelings and actions in the work context. When these needs are met, people react openly, creatively and cooperatively. However, if they are violated, the brain switches to protection and mistrust, withdrawal or even resistance arise.

1. Status: The need for recognition and appreciation

People constantly compare themselves with others, either consciously or unconsciously. Anyone who feels that they are slipping down the social hierarchy or being devalued perceives this as a threat. Status is therefore closely linked to self-esteem and identity.

Example: A committed employee receives public criticism in a team meeting for a detail of his presentation. Although the presentation was good overall, the critical tone remains. The employee withdraws over the next few weeks, contributes fewer ideas and seems insecure.

Why? Because his need for recognition has been violated. He feels belittled, especially because the criticism was public. Even small losses of status can trigger strong emotional reactions.

2. Certainty: The need for clarity and predictability

The brain loves patterns and reliability. Lack of clarity means insecurity – and insecurity causes stress. Particularly in times of change or restructuring, the need for orientation is especially pronounced.

Example: A manager announces a ‘major strategic realignment’ but remains vague about the specific implications. The team starts speculating: Will there be redundancies? Who will be affected? The mood deteriorates even though nothing has happened yet. Why? Because missing information is automatically filled with worst-case scenarios. Security means psychological stability. If it is lacking, trust in management declines and cooperation suffers.

3. Autonomy: The need for influence and control

People want to be able to control their own decisions and actions. If this sense of control is lacking, they experience powerlessness, which often leads to demotivation or passive resistance.

Example: a project team is presented with a detailed concept ‘from above’ – without the chance to contribute their own ideas. Although the topic is interesting, the employees show little commitment and only work on the bare essentials. Why? Because they have no control over how they should work. Autonomy not only increases motivation, but also the sense of responsibility. Those who have creative freedom are usually more committed and solution-oriented.

4. Relatedness: The need for belonging and trust

People are social beings. A sense of ‘we belong together’ is central to functioning teams. A lack of trust and closeness creates distance, misunderstandings and often conflicts.

Example: Two new colleagues are welcomed into the team but not actively included – neither in informal conversations nor in meetings. They remain silent, seem reserved and soon withdraw inwardly. Why? Because even unintentional social exclusion feels like real pain in the brain. Belonging is a basic need. If it is missing, motivation and commitment drop rapidly.

5. Fairness: The need for justice and transparency

When people perceive decisions or rules as unfair, they react emotionally, often even more strongly than they would to material losses. Justice is a moral foundation on which trust and loyalty are built.

Example: An employee finds out by chance that a colleague is getting a significantly higher salary for the same work. There is no explanation. The employee is frustrated, questions their loyalty to management and considers changing internally. Why? Because unequal treatment without comprehensible criteria massively violates the sense of justice. Even the appearance of unfairness can permanently disrupt cooperation.

Tips for applying the SCARF model

The SCARF model is most effective when it is not just understood as a theoretical construct, but is reflected upon and applied flexibly in specific everyday situations. The following tips show how you can implement the principles of the model effectively and in a nuanced way:

The SCARF dimensions do not work in isolation, but often simultaneously and with tensions.

The five needs are in a dynamic relationship with each other. A measure that strengthens the need for autonomy, for example, can simultaneously impair the feeling of security, for example when employees are given more responsibility but no clear orientation.

Tip: Never look at SCARF in a one-dimensional way. Successful leadership consists of controlling the needs as if on a mixing desk with several controllers as an overall picture.

It is not your intention that decides, but the perception of the employees.

Whether a need is strengthened or violated does not depend on objective facts, but on how it is experienced. Praise in a large group can trigger feelings of status and appreciation in one person and insecurity or shame in another.

Tip: deal with the individual perceptions of your team. Ask questions, observe and avoid assumptions.

Small gestures often have a more lasting effect than large measures.

While many managers apply the model to strategic decisions or change processes, its greatest strength often lies in the small things: an honest thank you, a friendly look, a moment of listening. It is precisely these micro-interactions that have a very strong influence on status, belonging or fairness.

Tip: Pay attention to details in your daily life. Your impact as a leader is not only created in big speeches, but in daily encounters.

Your own SCARF imprint influences your leadership logic

You yourself also have individual SCARF preferences. Those who have a strong need for autonomy tend to give others a lot of freedom, which can lead to insecurity for security-oriented team members.

Tip: Regularly reflect on your own SCARF landscape. It is a key to understanding why you react to certain situations in a particular way and why your team sometimes ticks very differently than you do.

Criticism of the SCARF model

As helpful as the SCARF model can be as a tool for reflection and communication, it is also important to keep its limitations in mind. Like any model, it simplifies complex psychological processes and does not claim to provide complete scientific explanations.

One key point of criticism relates to its empirical basis. Although the model is based on findings from neuroscience and social psychology, it has not been scientifically validated in the strict sense. It remains a theoretical framework that is characterised above all by its practical relevance and comprehensibility, but not by experimentally verified evidence. For scientifically oriented people, this may be a disadvantage, but for practical application it may be an advantage.

Furthermore, there is a risk that the model will be used too mechanistically as a checklist with which managers try to fulfil all five needs at the same time. However, people are individuals, their behaviour is context-dependent and not every need is equally important in every situation. Its application therefore requires sensitivity, empathy and situational adaptation, not rigid implementation.

In addition, SCARF largely ignores social, cultural and organisational parameters. It focuses strongly on individual perception and reaction and less on structural power relations, cultural differences or systemic dynamics, which also strongly influence behaviour.

Despite these criticisms, the SCARF model has proven itself in leadership practice many times over, especially as an impetus for reflection and as a language for social dynamics that are often difficult to grasp. It is crucial not to see the model as the ultimate truth, but as a source of inspiration for more conscious interaction.

Impulse to discuss

Which SCARF dimensions do you see as being particularly well fulfilled in our organisation, and where do you regularly perceive tensions or violations?

Notes:

[1] David Rock: SCARF: a brain-based model for collaborating with and influencing others

Here you will find a blog post by Stephan Pust: With SCARF towards a more agile organisation.

Here you will find a German-language video on the topic: Das SCARF Modell nach David Rock: Besser Führen mit Neuroleadership.

If you like the article or would like to discuss it, please feel free to share it in your network. And if you have any comments, please do not hesitate to send us a message.

Here you can find additional information from our Smartpedia section: