Using conflicts in the team productively

Q: Tell me, do you sometimes have conflicts in the team?

A: Sure, all the time. This morning we got really involved in a technical decision, so we sometimes have to use strong words.

Q: And what does that do to the atmosphere in the team?

A: Nothing. I know that the others just want to do a good job. There are just sometimes different opinions about what constitutes good work.

Q: How did you resolve the situation this morning?

A: After discussing our points of view, we came up with a solution that everyone can live with. If that hadn’t worked out, our team leader would have had to put his foot down.

Q: And what happens after that?

A: Well, we go to lunch together and everything is fine again. The others don’t mean any offence. I’m more grateful to them when they honestly say that my idea is rubbish.

Smooth collaboration within the team

The other day at a Meetup, the question was asked: “How do we achieve smooth collaboration in a team?”

This question irritates me. Not because smooth collaboration is not possible, but because I am convinced that it is not at all desirable in terms of decision-making and results.

The sentence “There is a conflict in the team” automatically sets the pulse of managers and team developers racing. In most organisations, conflict is seen as something bad and destructive – a “disruption in the flow of operations”, a (hopefully) rare dysfunction in the normally harmonious cooperation. A good team is characterised (in this view) by the fact that everyone pursues common goals and interests, decisions are made by consensus wherever possible and everyday life is characterised by unity. Classical management theory with its mechanistic view of the world has left deep marks here. Successful organisations are often compared to “well-oiled machines” – such a machine has as little friction as possible, because friction means wear and inefficiency.

I would like to counter this idea with a contrary view; a perspective in which conflicts are not only unavoidable, but even necessary and beneficial for successful collaboration. Without conflict, weaknesses are not questioned, alternatives are not explored and optimisation potential is not exploited. In my view, it is not a question of avoiding them, but of using them as a tool and resource for joint success. How this works is not just a methodological question. There are tools that can help us do this, but above all, it requires a paradigm shift in the way we deal with our fellow human beings.

Conflicts and organisations

If you look at the topic through the lens of social theory, it quickly becomes clear that conflicts are fundamentally and permanently woven into organisations. Organisations exist because three different stakeholder groups (customers, owners, employees) can simultaneously derive different benefits from them. An intersection of common interests ensures that cooperation takes place at all, while at the same time these interests conflict with each other elsewhere. The resulting conflicts of objectives create a permanent need for communication and decision-making that has to be addressed time and again. Organisations cannot escape this fundamental tension of partial but not complete agreement. Wherever people work together, there will always be different views on when and for whom the collaboration has what added value.¹

Organisations have various ways of dealing with these ongoing conflicts. One option is the classic division of labour, in which different areas of the organisation are responsible for different interests. This works, but shifts the conflicts to the interfaces between these areas, where they can quickly degenerate into political power struggles and cause frustration on all sides (“Sales is getting in the way again…”). Another option is to transfer an entire topic with all its potential for conflict to a team, which can then (hopefully) handle the necessary discussions and decisions in a small circle more quickly and effectively than the large organisation outside. Terms such as “interdisciplinary”, “cross-functional” or “cross-departmental” in relation to teams express the fact that very different expertise, perspectives and interests clash and should clash in them on a daily basis. Differences of opinion are part and parcel of such teams, that much is clear – and not by accident, but by design. Seen in this light, many teams seem less like “well-oiled machines” and more like deliberately defined arenas for conflict management.

These considerations coincide with my practical experience that particularly successful and high-performing teams are not characterised by harmony, but by tension and dissent. In high-performance teams (a term with positive connotations for me), people often argue with each other with a directness that is shocking to outsiders, without this having a negative impact on the team members’ continued cooperation. Topics are vigorously discussed, options compared, different points of view attacked and defended, then the team members have a relaxed meal together and chat about the weekend as if nothing had happened. In my experience, the need for conflict (!) in a team increases with the internal dependency of the team members on each other and with the performance-orientation of the team. A group that absolutely has to and wants to deliver, but whose members can only achieve results together, must be able to argue or it will break up.

What characterises high-performance teams is not the absence of conflict, but the reflected and controlled handling of it. The art lies in being able to deal with conflicts openly on a professional level without escalating to a personal level – for this to happen, it is essential that all team members know and trust that conflicts will be dealt with in this way. In my experience, this prerequisite has little to do with the personalities of the team members, but all the more with the rules and expectations within the social system “team”. People are ready and willing to engage in a professional debate vigorously but constructively as long as the “rules of the game” of the situation encourage such a debate and at the same time mark personal attacks as inadmissible.

These rules of the game are no coincidence, but can be consciously designed for a specific context. Examples of “conflict-friendly” contexts range from the plenary debate in parliament to the rhetoric club at university to the political debate in the kitchen of a shared flat – wherever people know that there is a subtle but important difference between professional debate and “real”, lasting relationships. One key to developing successful teams lies in establishing day-to-day collaboration as a social context in which professional issues can be openly debated, but at the same time interpersonal relationships are nurtured and kept intact. Both expectations are important and must not only be established initially, but also reinforced and honed over the life of a team. Let’s take a look at how this can work.

Common conflict models

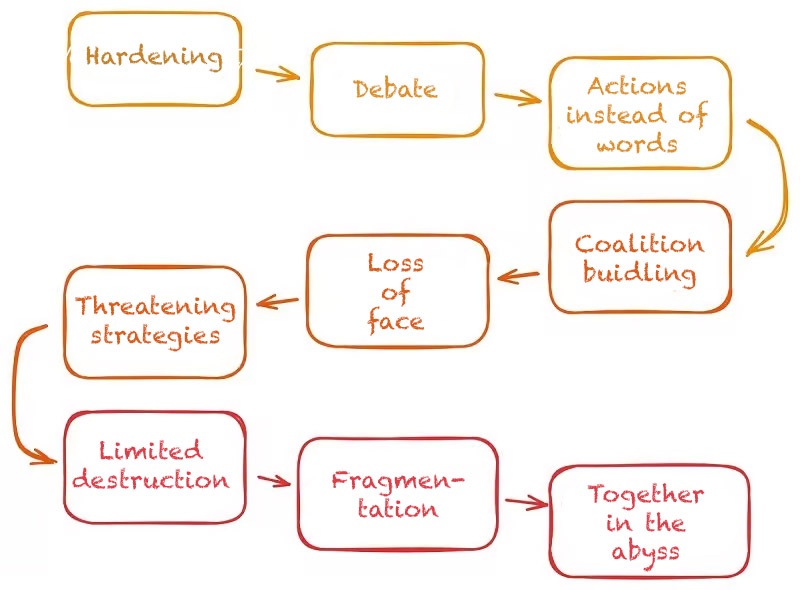

Anyone who wants to work consciously with conflicts must be able to observe them and differentiate between constructive and destructive. A widely used tool for this is the nine-stage escalation model developed by conflict researcher Friedrich Glasl.²

The Glasl model provides two important insights for teamwork:

- Professional disputes, even heated ones, are normal and to be expected in day-to-day dealings and rarely require corrective intervention. In most cases, it is sufficient to focus on a solution-orientated discourse and exclude personal attacks as inadmissible. A critical turning point in a dispute is when communication is broken off: “Talking to him won’t help anyway.”

- As soon as people start talking about each other instead of with each other, this opens the door to a number of dangerous dynamics. Teams can monitor their own communication for such situations, prevent the formation of camps and work towards resolving differences of opinion through dialogue before frustration and the breakdown of dialogue occur.

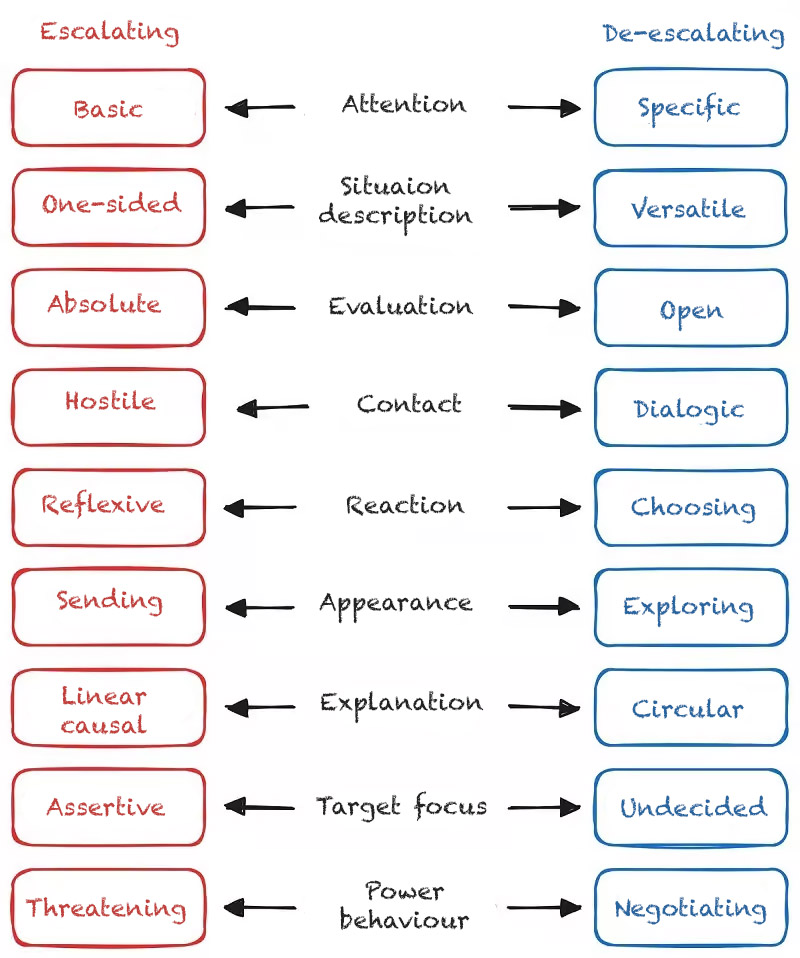

Another helpful model comes from the organisational consultant and coach Klaus Eidenschink, who uses a series of conflict facets to illustrate various possible strategies for action:

- On the one hand, conflict behaviour is often not a linear sequence of escalation stages, but rather a broad spectrum of different behaviours that can be selected and combined with each other almost at will. For example, it is perfectly possible to combine a friendly tone on the social level with a total refusal to engage on the factual level.

- On the other hand, Klaus Eidenschink emphasises that conflicts can be useful and necessary in many cases and therefore the confident mastery of both escalation and de-escalation strategies is crucial for dealing with conflicts in a healthy way.

I would like to emphasise this once again: Contrary to what is taught in many conflict seminars, it is important for healthy day-to-day teamwork to be able to be contentious, one-sided, broadcasting, assertive, egotistical etc. when the situation and the factual issue require it! The trick is to do this consciously and reflectively, in a controlled manner, and to be able to promptly transform the resulting conflict back into a professionally and socially acceptable solution.

Six practical tips for using conflicts productively

Finally, a few ideas and tips on how teams can use conflicts productively:

We are clear on the issue, but appreciative in our approach.

While conflicts at the level of factual issues, procedural options, objectives and priorities are normal and even necessary for teams, personal conflicts have rarely proved helpful in practice. A basic rule for teamwork could therefore be:

Factual issues may be discussed clearly and sometimes emotionally, but attacks on the intelligence, competence or goodwill of the other participants are absolutely unacceptable. Whether you reject an idea with the words: “I understand what you want, but it doesn’t work for me”, or whether you open a conflict on the relationship level with: “I think it’s a cheek that you’re making this suggestion at all”, makes a big difference to the further course of the discussion.

It is up to the team to establish this rule together and then enforce it together! A common mistake is to implicitly assume that rules like this are “obvious” – in my opinion, it doesn’t go without saying that a tough technical debate is desirable in any meeting. I myself explicitly state the rule “clear on the matter, respectful in my dealings” at the beginning of my workshops, for example, making it clear that I regard it as a prerequisite for participation in the meeting. The effect on the further course of the workshop is noticeable, not only in the form of better discussions, but the “permission” to clearly disagree on the matter also noticeably relaxes the participants emotionally.

Open up conflicts when they are necessary – but only then.

If we consider conflicts to be good and necessary, then the question of which conflicts we open up (and how!) is of course crucial for cooperation. Not every disagreement necessarily advances the common cause. Intervening at the right moment with the right words needs to be practised.

One of the social functions of conflict is to highlight alternatives to the status quo. A reason to start a conflict can therefore arise when certain alternatives have not yet been sufficiently considered. The mere perception of “hmm, but I personally would do it differently”, on the other hand, is generally not a sufficient cause. Different styles must also be tolerated in a team. In case of doubt, the moderator of a meeting must decide which discussions and objections should be given space.

The supreme discipline: being able to make decisions even if you disagree.

Conflicts are resolved through decisions. Agreement by consensus is only one way of making this decision – and if we want to preserve the diversity of perspectives in the team as a resource, unity is not necessarily something we should always strive for!

So the team needs opportunities to make decisions without having to agree. One way that I have found very successful is to appoint “topic owners” who can listen to and integrate different perspectives and, in case of doubt, have the final say by means of a consultative individual decision. This role is respected as such and its existence and appointment is not questioned during the ongoing debate. Otherwise, the team needs decision-making methods that can lead to results despite disagreement – majority votes and resistance polls are ideal.

Proposals are secondary, interests are decisive.

Many debates often revolve around the question of which proposal from a range of options should be prioritised. The problem with proposals is that they are very specific and often laden with personal preferences that are difficult to understand – both of which make it difficult to find the best possible solution. A helpful principle from the Harvard negotiation method is to conduct the dialogue not about proposals, but about the interests behind them: “Why is this proposal so important to you?” Suggestions thus become a fleeting part of the discussion and can come and go as demand dictates, while the participants explore each other’s ideas and needs.

Normalise, value and consciously challenge dissent.

Very few of us ever consciously learn how to open a conflict in a controlled way – as a result, we feel insecure and embarrassed just by raising an issue and are sensitive to rejection. It is therefore important to create an atmosphere in the team in which both disagreement and the rejection of suggestions are possible at any time without anyone feeling attacked.

An important ritual here is to value dissent at every opportunity: “Thank you for allowing us to discuss this so openly – your objections and counter-proposals have really made the result better today”. Dissent can also be explicitly marked as welcome at the start of a discussion or meeting. Here is an example of how I would open a working session with a team colleague:

“”Thank you for taking the time. I had a bad idea and I hope you can help me turn it into a good idea. I don’t necessarily need you to tell me what’s great about it – I’m already convinced of that. You would help me the most today if you could show me what weaknesses and blind spots my idea still has at the moment.”

The way we deal with drafts and interim results also has a major influence on the perception of dissent in the team. I now avoid showing my team “finished” results for which I would rather not listen to criticism. Instead, I involve my team where they can and should make a tangible difference: with half-finished drafts, rough sketches of solutions, initial ideas and prototypes. Because I know that these interim results are not yet particularly good (and don’t have to be), I can also accept and integrate harsh criticism much better in this phase.

Use check-in and check-out as key rituals.

A working day that consists of 8 hours of conflict and tough arguments every day would be extremely exhausting and tiring. In every collaboration, we need periods of time in which we can simply understand each other well and encourage each other. For the targeted use of conflict, it can therefore be helpful to explicitly define phases in which dissent is necessary and to open and close them with appropriate rituals.

A check-in and check-out at the beginning and end of a meeting or workshop is predestined for this. The beginning of a meeting can be used, for example, to explicitly invite objections and objections, define rules of behaviour and clarify how decisions are to be made and objections integrated. At the end of a meeting, the commitment of those involved is recognised once again, any tensions in the relationship are resolved (“I didn’t mean any offence earlier”) and the framework is closed again. It is ideal if an opportunity for relaxed socialising can be created immediately afterwards, e.g. by having a meal together or a relaxed coffee break in the fresh air. In a way, these small rituals are similar to the ceremonial bowing at the beginning and end of a sparring session in martial arts – not only do they clearly mark the boundaries of the confrontation for all to see, they also express mutual respect and gratitude for participation.

Conclusion

To be successful, organisations always need a balance between stability and change, clarity and ambiguity, agreement and conflict. Collaboration in which there is no room for contradiction and objections stagnates and ossifies over time, building up pressure and dissatisfaction that will sooner or later have to find another outlet. I therefore personally do not find the widespread narrative that harmony in a team is good and conflict is bad helpful.

The ability to argue is an essential prerequisite for successful teamwork. Like most other skills, arguing and dealing with conflict must be practised consciously and regularly. Instead of denying this fact in favour of “harmonious cooperation”, it is better for teams to create explicit spaces for this and to negotiate together when and how contradictions and differences of opinion can best be used to achieve good results. The 6 tips listed above are a good practical aid; each tip is effective in its own right, but together they form a very good basis for utilising conflicts in a team productively. Simply try them out for yourself at the next opportunity.

Notes (partly in German):

If you like this article or would like to discuss it, please feel free to share it in your network.

[1] Very clearly explained e.g. in Simon, F. B. (2021). Einführung in die systemische Organisationstheorie. Carl-Auer Verlag, Kapitel 3.1.

[2] See e.g. Glasl, F. (2020). Konfliktmanagement: Ein Handbuch für Führung, Beratung und Mediation (12. Aufl.). Freies Geistesleben. S. 243.

[3] Eidenschink, K. (2024). Die Kunst des Konflikts: Konflikte schüren und beruhigen lernen. Carl-Auer Verlag.

Kai-Marian Pukall has been working with agile and self-organised teams for over twelve years. For three years, he accompanied one of the largest transformations in the German-speaking world as an Agile Coaches at DB Systel. He is currently a senior consultant for Chili and Change, advising clients throughout Germany on how to improve their collaboration. His work focuses on the realisation that particularly successful teams are often characterised by aspects such as voluntary membership, a high level of commitment and clear internal structures. His book Selbstorganisation im Team is about how to achieve this state as a team. Well worth reading!

Kai-Marian Pukall has published further articles in the t2informatik Blog, including:

Kai-Marian Pukall

Kai-Marian Pukall works as an organisational consultant for Seibert Media GmbH. He has been accompanying agile teams for many years, always with the aim of making collaboration valuable and professional, simple and people-friendly. He prefers to apply the Lean principle “Eliminate Waste” to everything that smells like method and business theatre.