Three questions about change management

An interview with Stephanie Borgert about change management

Stephanie Borgert has a degree in computer science, is a complexity researcher and has been a business columnist for the Frankfurter Rundschau for many years. The high level of networking, dynamism, lack of transparency and unpredictability of our complex world drive her to find the right answers to the associated management challenges. And that makes her exactly the right person to answer the following three questions on change management:

What inappropriate narratives about change persist in the organisational world?

Stephanie Borgert: The many decades of preaching change management have implanted some narratives in the subconscious, so that people often don’t realise which explanatory model they are using to think about change. And so the narrative of people’s resistance comes up almost reflexively. Sometimes a distinction is made – then it is increasingly the older colleagues who find reform difficult. Quite apart from the ageism it implies, this assumption has fatal consequences. If we believe this, then we will focus our catalogue of measures entirely on people. We want to turn them from victims into participants, to take them along, to lift them up, to anticipate their resistance. Everything revolves around people. As if it were the individual who would bring about change. In my view, based on systems theory, this is not the case at all. Context creates behaviour. So instead of ‘updating’ people, we need to work on the system.

Another myth related to the first is that of communication. If the change communication is good, meaningful and engaging, then people will follow and the transformation will happen. This naive, rosy picture is nice, but it misses the point. No matter how fancy the speeches made by leaders at town hall meetings, communication starts with the receiver. Unidirectional communication is always a gamble – we don’t know what will be understood and interpreted and how. So the idea that all that is needed is to communicate the meaning and purpose of the change effort well enough is outdated.

In my opinion, the greatest imbalance is still created by the idea that a few people conceive, plan and announce the change and then an entire organisation marches in lockstep. So often, even in agile contexts, I see transformation offices conferring in secret and then one day coming up with a colourful PowerPoint presentation. If this approach is scrutinised, the narrative is revealed: our people don’t have the overview to join in the discussion. They can’t do that. Sometimes I want to ask whether they have hired the right people in recent years. Everyone is supposed to work independently, creatively and in a future-orientated way, but they don’t have the insight to participate in the change project?

How does a collective understanding of change emerge in an organisation?

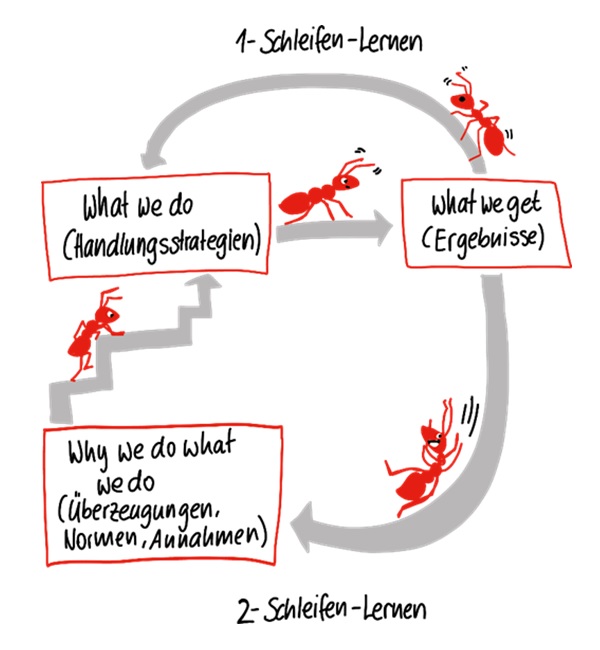

Stephanie Borgert: Through debate, organisational discourse (as I call it). That’s the short answer. It’s much more than exchanging opinions or quickly agreeing on measures. Discourse is an intensive debate about the collective evaluation patterns, norms and convictions that characterise people’s actions. In many organisations, there has been too little reflection on this to date. There is a lot of talk about the what of work, but not enough about the how. Chris Argyris, the father of the learning organisation¹, distinguishes between 1-loop and 2-loop learning. This makes it easy to visualise.

Illustration by Sandra Schulze from “Gemeinsam denken, wirksam verändern” (Stephanie Borgert)²

A (classic) example; a company wants to act more flexibly and increase the autonomy of its teams, so it decides to work in an agile way.

First measure: Scrum is introduced in IT. They now do daily stand-ups, planning poker and iterations. After a while, you realise that nothing has changed in terms of autonomy. The business is intervening, changing the planning cycle and the managers are getting involved. If change now takes place at the same level, the action strategy is corrected. A different cycle for meetings may be considered, the iterations extended or a team leader appointed again. Attempts are made to influence the results via methods and processes. This does not work with fundamental changes because the level of norms, basic assumptions and beliefs is not reflected. But this is exactly what influences behavior. This is why two-loop learning is called for, and with it the examination of “Why we do what we do”.

Inviting the organisation to reflect in this way is a powerful tool to enable a shared sense of purpose and to approach change with genuine participation.

What does it take to bring about serious change?

Stephanie Borgert: Let me try to condense the “ingredients for successful change” down to the most essential ones.

1. a relevant problem

“We’re doing design thinking now because it’s so creative” is not enough. We would like to or would like to sometimes, does not describe a relevant problem. And this is important because relevance is central to change in complex systems. After all, it is the organisation itself that, as a complex system, likes to maintain its established routines and patterns. If they are to be changed, then it is for a good reason. It is also easier for people to understand if the change has organisational relevance.

2. a sponsor with formal power

Fundamental changes are always also structural changes (formal and informal). This means that at least one person with the formal power to establish or dismantle such structures is required. Without a sponsor, the many initiatives along the lines of “Why don’t you change now, but everything will stay as it is” will come to nothing. The role of the sponsor should not be confused with that of an advertising ambassador. It cannot be delegated or done casually on the side.

3. create and endure instability

Changes that get down to the nitty gritty generate a lot of questions and uncertainty. “If we become agile now, where is my place in the team?” “We are now supposed to do team-based solution sales. What is my role in this?” Instability arises because questions arise, ideas are discussed and “the system” deals with itself. This instability has to be endured, for managers as well as for all employees, because they are all in the same rocking boat and together do not have an immediate answer to everything. At the same time, change needs this instability, because without it, nothing can fundamentally change. Pattern changes do not work without instability. This costs energy and nerves, always and for everyone.

A sensible way of dealing with it is to stimulate discourse within the organisation and create space and opportunities for this intensive debate.

4. openness to solutions

A special feature of organisations is that they cannot be predicted in detail. So if we all become agile now, it is impossible to describe in advance exactly what this means at every point and what effects it will have. Control is and remains an illusion. It is therefore necessary to be open to alternative outcomes that may not meet the expectations of the secret transformation office. It is not about questioning the change itself, but its concrete implementation must be the playing field for the discourse. Otherwise, we run the risk of treating organisations like trivial machines. And if we do that, we will continue to tell ourselves the narratives from the first question, from one failed change undertaking to the next.

Notes:

[1] Argyris, Chris/Schoen, Donald A.: Die lernende Organisation, Schäffer-Poeschel Verlag, 1996.

[2] Borgert, Stephanie: Gemeinsam denken, wirksam veraendern. Organisationaler Diskurs als Schluessel zum Change, Vahlen, 2024.

Illustration: Sandra Schulze

Are you looking for support in change management? Then simply get in touch with Stephanie Borgert.

Stephanie Borgert has published three posts on the t2informatik Blog about Change resistance in a team, ““We need training!” and Power and self-exploitation.

If you like the article or would like to discuss it, please feel free to share it in your network.

There are more posts from the t2informatik blog series “Three questions …”:

Michael Schenkel

Head of Marketing, t2informatik GmbH

Michael Schenkel has a heart for marketing – so it is fitting that he is responsible for marketing at t2informatik. He enjoys blogging, likes changes of perspective and tries to provide useful information here on the blog at a time when there is a lot of talk about people’s declining attention spans. For example, the new series “Three questions …”.