The secret superpower for project managers

What do you think of when you hear about a superpower? Superman, Wonder Woman, the Hulk? It’s the superpowers of these superheroes that make an impression. Where the Hulk goes, no grass grows. And if Superman can orb the Earth fast enough, then the Earth will spin with him, and time will go backwards. Not very realistic, but pretty impressive. Superman knows what he can do and so does everybody else.

Here and now, however, we are supposed to be dealing with a superpower that is invisible in two respects: On the one hand, most people don’t even know it exists – often not even those who have it at their disposal – and on the other hand, it is hardly noticed even by those to whom it is applied. What is most noticeable are the results, and they are impressive. It is a superpower that makes mediocre projects successful and helps average employees to achieve great careers. But when that superpower is missing, the exact opposite happens. Well-designed projects with qualified teams become failures, and talented employees must never show their true potential.

What is the superpower? Quite simply, it’s about the ability to get the decisions you need for yourself, your project and your team from other people – often from supervisors to top management. Because just as a successful career does not depend exclusively on the competence of the career aspirant, the qualifications of the team members or the quality of the project work do not always determine success in projects.

What makes projects successful … and what kills them

“Wait a minute” you may now throw in, “of course, the qualification of the team members or the quality of the project work decide on the success of a project!”

I guess so. But not only. And often not even in the first place. To see that, let’s look at two prototypical projects and their development: Project A is the way it should be. The goal is clear, the project is well planned, resources are available in sufficient quantities, and the team is qualified. Project B is closer to the project reality as we find it in the free corporate wildlife. The goal is halfway clear, the project manager has given the project some rough thought, resources are lacking, and the employees who would actually need it are always represented by colleagues who still need to be trained.

If you had to bet on which of the two projects would be a success, your choice would clearly be Project A, right?

Let us look at the two projects three months later, it is time for the second project steering committee. The project leader of project A is going into the appointment in good spirits, he is top prepared to get the go for the next project phase. No sooner does he start with the agenda than he is already interrupted with a detailed question. He can answer it reasonably well, when the next cross shot is already coming. One hour and many questions later he is tired and frustrated. The decision for the next project phase is not in his pocket. But he does have detailed questions and work orders that his team will have to deal with over the next few weeks. But the really unpleasant thing is that the next steering board is not for two months. The project manager was careful to find out if it would be possible to find an appointment earlier? No chance! Unless another miracle happens, the schedule and the project budget will blow up in his face, and he doesn’t know how to keep the team motivated over the next two months. Within only one meeting the sample project A has become a horror project A. And yet the project manager has done nothing wrong!

The project manager of project B has much less in her luggage. Over the past few months, there have been rumblings and crunches on every corner and it’s been hard to be productive. She starts the appointment and asks first if she should proceed according to the agenda or if she should go deeper at one point. The CEO looks up briefly and releases the agenda with a “Nah, just do it!” The project manager briefly thanks him, asks whether she can start right away with the essential points, and receives approval for this as well. The most important point from her point of view is clear. It is not what has been achieved so far, nor the difficult resource situation in the team. The most important thing is the decision of the project steering committee for the next project phase, and that is where she starts. “My team and I, we have looked at three different alternatives for the next phase. Our recommendation today is to start the next phase of the project, and to provide the project with more resources at the same time!” She senses the emerging resistance, and without pausing, she continues “You probably want to know what options we looked at and how we came to this recommendation of all things, don’t you?” That is exactly what the steering committee members wanted to know, so they get back their approval. Barely twenty minutes later the meeting is over. The project manager has achieved all her goals. She has the go-ahead for the next phase of the project, and she also has more resources. Within just one meeting, Project B became a project with the best chances of success.

The difference? The project manager of project A did nothing wrong. ” Those at the top” didn’t make a decision. And yet it will be him who does not deliver his project results on time and within budget. He’s got a bad feeling about what this means for his career.

The project manager of project B, on the other hand, was able to do what only a few can do. And she knew what only a few know: you can learn to prepare decisions in such a way that decision-makers make quick and reliable decisions.

Why no one has the competence “getting decisions” on the radar

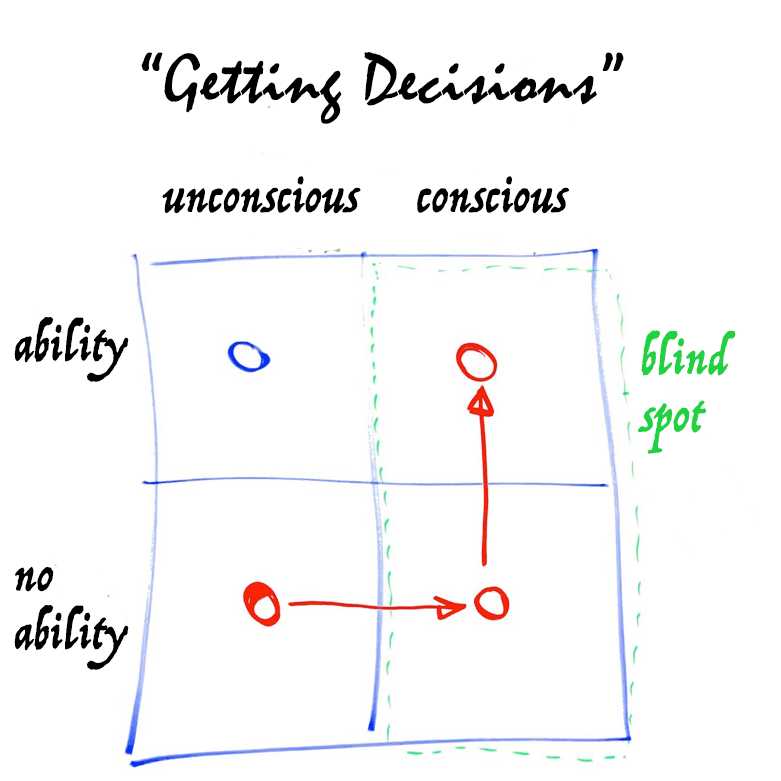

Recently, I was invited to speak at the alumni event of a large strategy consultancy on the topic of “getting decisions”. At the beginning I drew the following sketch on the flipchart (yes, I know, it could be nicer…)

Do you recognize the pattern? It’s the learning phase model that Bandura, Ross and Ross introduced back in 1963. In this case using the example of “getting decisions”.

Next, I turned to my listeners and asked a question: “Let’s assume that ‘getting decisions’ is a competence. Is it a competence that many people have or a competence that few people have?“

After a brief discussion, it was clear that few people have that ability. Most project managers, executives and normal employees complain that they often leave a meeting with the management without a decision, but with an additional work order.

My next question: “Let’s look at the majority, those who do not have this ability. Are they aware that there is the competence to ‘get decisions’? Are they saying ‘getting decisions is a competence, but I just can’t do it’ or are they saying ‘I do everything right, always prepare everything properly, but the idiots up there just don’t decide’?“

Some of the audience had to laugh. Clearly, many employees who do not receive a decision see the mistake in the others rather than in themselves. “It’s the fault of the top guys.” So most of the people in my drawing are to be found in the lower left. They don’t know how “getting decisions” works, and they are not aware that there is something to be done.

But I wasn’t finished yet: “All right! Then let us now take a look at the minority. On people who are good at getting decisions. Where do we usually find them when we think of a company? What decisions are they gonna try to get if they’re even a little bit selfish?“

Now some more had to laugh. Some of the former consultants felt caught. And the answer to my question was quickly found. Employees who are capable of getting decisions are often found higher up the hierarchy. After all, the question of who should be promoted is also a management decision. If you know how you can influence them, you have a good chance when it comes to careers.

So he continues: “Let’s think again about the few people who are able to make decisions. What do you hear from them when you ask them about the reasons for their success? Do they tell you that they were promoted because they can get decisions? Or do they tell you that they are simply good, that they have had the right training, that they have been diligent and persevering, or that they simply had the right mentor?“

Most listeners laughed. The penny had dropped. Because of course the ability to get the decisions you need from your supervisor or top management is a career boost. At the same time, hardly anyone is aware of this and looks for the reasons for their own success elsewhere. Those who are good at getting the decisions they need are often unaware of this competence and can be found in the top left corner of my drawing.

The really exciting thing is that although “getting decisions” is a competence that can save projects and promote careers, hardly anyone is aware of it. The whole right (conscious) side of my drawing is a big blind spot. The competence “getting decisions” does exist, but hardly anyone has it on the radar. Most people who have this competence blame other abilities for their success. And most who do not have this competence blame other people or external circumstances for their failure.

And so the circle is complete. Anyone who is able to obtain decisions from his superiors or customers quickly and reliably has a superpower. But it is a superpower that no one notices. Again using the example from before: the meeting drags on like chewing gum and ends without a decision? A clear case from the decision-makers’ point of view: “The project manager did not prepare this well! Alternative: the meeting ends half an hour earlier with a decision? A clear case from the decision-makers’ point of view: “We did a good job today!”

Unbelievable, but true: if you get better at getting decisions, then everything will be much more relaxed and easier, but hardly anyone will notice that you are doing anything different. So you don’t have to ask anyone’s permission.

And finally: it is a competence with which you can benefit yourself and your projects, your team and your topics without harming anyone. Because especially in times of increasing dynamics and a clouding economy, not only good but also quick decisions are worth their weight in gold.

And how does “getting decisions” work?

The question remains what you can do to get the decisions you need for yourself and your work from your decision makers. The following points serve as a guideline:

- Take the perspective of the decision makers!

- Understand what type of decision you are dealing with and what the motives for the decision are!

- Respect typical decision-maker needs! For example, get to the point and let the decision-maker decide!

- Determine the interests of the decision-maker systematically!

- Communicate pyramidally!

Notes:

You are welcome to share or link to the content on this page.

Georg Jocham has published another post in the t2informatik Blog:

Georg Jocham

Georg Jocham is an author, management trainer and university lecturer at the Vienna University of Economics and Business Administration.

After several years in strategy consulting (Roland Berger), he worked in various management roles in the corporate environment before becoming a freelance trainer. His focus is on executive communication (“How do I get management to make the decisions I need for my work?”).

He completed his training at the University of Innsbruck, the Universitá La Sapienza in Rome and the Vienna University of Technology. With his podcast “Abenteuer Problemlösen” (Adventure Problem Solving) he has already topped the iTunes charts several times and reaches tens of thousands of listeners every month. In 2019 his book Schneller Entscheidungen bekommen – Die besten Strategien und effektivsten Methoden“ (Getting faster decisions – The best strategies and most effective methods) was published by Redline / Munich publishing group.