Resilience is more than a buzzword

Why resilience is more than a buzzword and what it means for your employees

In view of the ever-increasing number of catchwords, some people have the fun of introducing a buzzword bingo when the number of buzzwords becomes too large. The currently frequently used terms include, for example.

#mindfulness,

#agility,

#awareness,

#mindset,

#resilience,

#selfcare,

#VUCA,

#WOL,

#Zen or

#ZRM.

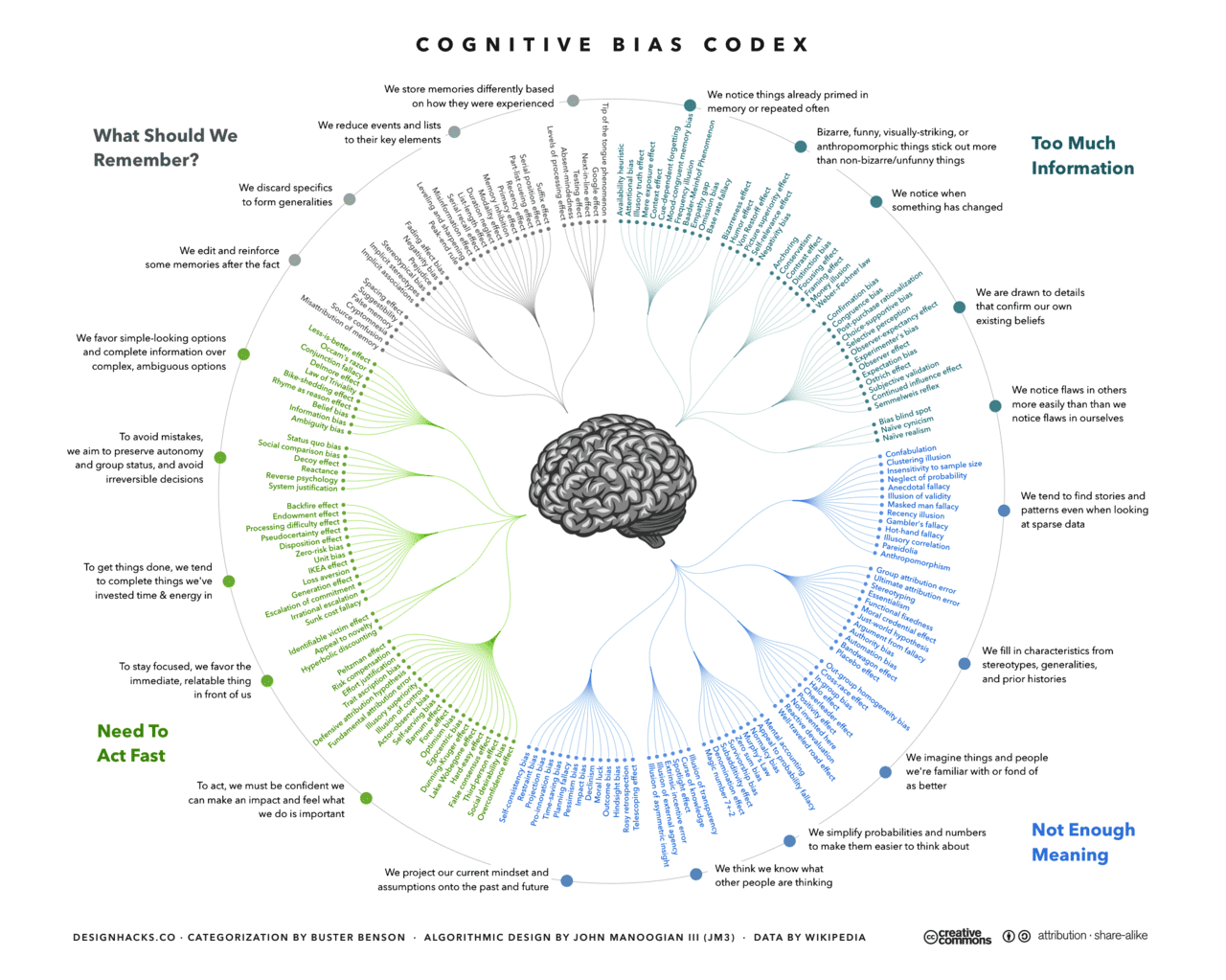

The principles behind these buzzwords are often many decades to centuries old. These topics become buzzwords when we have the impression that we hear them more and more often and they seem to have a significant relevance for our lives. Essential to this impression is the #confirmationbias, with which we unconsciously filter the news flowing around us for corresponding keywords. Our brain is constantly trying to recognise patterns in our sensory impressions in order to have less work to do.

Moreover, buzzwords often promise simple answers in a complex, you know it: #VUCA world. But because our brain gets bored quickly on the one hand and always needs new nourishment1, and on the other hand has a limited range of receptivity, we have the impression one has to make a big fuss again every year. Suddenly VUCA becomes unimportant, BANI appears and suddenly there is a new topic for the next small talk.

The confirmation bias and the selectivity of our brain

You may be familiar with the confirmation bias: You are interested in a certain new car, say a blue Tesla, and suddenly you spot an extraordinary number of blue Teslas on the road. Or you read a book that confirms your previous world view and you think: “That’s a good book”. Yet this confirmation bias is only one of dozens of filter functions with which our brain makes itself more comfortable, protects itself from being overwhelmed or keeps us alive:2

The human filter functions primarily limit what we consciously perceive. Our subconscious, however, is aware of much more. The easiest way to notice this is with reflexes, e.g. when our eyelid closes without thinking as soon as a foreign object approaches, or we have a “funny feeling” or feel aversion in certain situations or with certain people without knowing the reason for it. There are explanations that this is like the iceberg, where only about 10 percent is visible above the water level.3 “Under water” lies the “gigantic subconscious”.

Fear and resilience

We can tolerate the impressions swirling around us more or less well, depending on the individual. It seems that there are more and more people who suffer from their (bingo!) #highsensitivity. At the latest when we get the impression of being driven, our heads spin or we even notice an uneasy feeling in our stomach or mood swings because we feel (bingo!) #FOMO, it is time to pause. FOMO is the fear of missing out on something important. Something that we may consider existential because without this “important” we may be socially relegated, socially excluded or whatever the extreme thought behind it may be.

It is in relation to this fear that resilience comes into play. You don’t know FOMO? Haven’t you caught yourself scrolling through the timeline of your Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn or Facebook app for an extended period of time as if you were under someone else’s control, wondering where the time went or what you were doing there for so long? Have you never written an outraged post about anything? Great! Then you either have naturally high resilience or you have trained it well. You also have good resilience if you remain calm and confident in crises, keep an overview, are adaptable to rapid changes, are less prone to illness, etc.

Please stop for a moment and answer these coaching questions for yourself:

- How long do you think you would survive (in the Alps in summer) seriously injured in a crevasse?

- Which people would you trust more and why?

My favourite anecdote on the subject of resilience is that of the 70-year-old mountaineer who survived for a whole 6 days with a broken hip in a Tyrolean glacier in 2012. He was only heard because he was still calling for help on the sixth day.

A rescuer said at the time: “I don’t know of any case where someone has ever survived in a crevasse for so long.” But the decisive factor, according to the attending physician Volker Wenzel, was that the climber never gave up hope.4

Many other people have natural resilience, they are “stalwarts” who have fought their way back into life after difficult life events, such as Samuel Koch after his accident on “Wetten dass…”.5 Others have found a “successful” life with a life biography with a “difficult” childhood, such as Christian Peter Dogs.6

But what can you do if you want to improve your resilience?

Resilience and muscles

Now comes the good news if you want to improve your resilience:

While early research concluded that resilience, the defensive power of the psyche, was due to personality traits, current research is further along and has recognised changing personality states and habits that make resilience malleable.

And indeed, the evidence also shows that you can train resilience like a muscle with a procedure I use in practical integrative cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders. And like a muscle, the demand must be strenuous but manageable. Otherwise the muscle, or resilience, does not build up.

Another coaching question:

- Imagine you are shipwrecked in survivable warm water and have no idea in which direction the saving shore lies. All you know is that it is not far away and you have a minimal chance of reaching it. What would you do? Just give up or at least swim off somewhere to take your chance?

If you apply this metaphor to your life, you will realise that you often have more chances and opportunities than you probably initially believe.

That’s why I believe: Good resilience training is not a wellness programme or self-optimisation, but an important element for mental health. It gives you the opportunity to recognise more often the chances, possibilities and opportunities of the present and to actively shape your life.

Resilience in companies

In the meantime, many companies (and also nations7) are dealing with the topic of resilience. Since the topic – the term resilience is derived from the Latin “resiliare” and means to bounce back – is used not only in psychology but also in other sciences, there are different perceptions and interpretations of resilience.

I would like to clearly contradict an image that I simply do not consider helpful: Resilience does not mean enduring grievances without resistance and thus becoming apolitical, for example. Often, examples of Nelson Mandela, Viktor Frankl or other prisoners are used to explain that with the appropriate inner attitude, one can also better survive a difficult superior, a lousy working climate or difficult personal circumstances if one goes through a kind of “survival camp”. For me, this falls far short of the mark.

Good resilience training puts you in a position to increase your “situational awareness”, among other things. I have found this concept particularly useful in pilot training. Translated to life on the ground, this means: After good training, you are more often and better able to recognise your own resources, your creative spaces as well as possible, beneficial changes in perspective and to notice when and how you can ally with other people or other teams for the good of the overall system.

Less resilient people fall into brooding loops, victim roles, depression or blind activism more quickly or for longer. They ride the “brain lift”8 downwards. And with them, entire teams or organisations.

This means that resilient people are the basis for resilient teams. They can react faster and better to current crises9, because they remain “clearer in the head”.

Conclusion

Why is resilience more than just a buzzword and not another topic of seemingly endless self-optimisation?

In my opinion, this is because resilience is already inherent in us and that appropriate training is anything but a luxury good. Sometimes we lose it under certain conditions, sometimes it is favoured.

I understand resilience as the ability to move on two legs. If we move too little, we endanger our health. If we move regularly, we promote our health. Light, regular exercise in the fresh air is not used for nothing in the treatment of depression. It also supports our well-being in general much more than an hour on the sofa with Netflix and co.

I see it similarly with resilience. For example, if you spend 30-60 minutes regularly with yourself instead of social media or matters beyond your control, or you meditate a bit instead of distracting yourself, practice acceptance without resigning, practice confidence instead of seeing black for the future, then you strengthen your resilience.

As a consequence

- you will get less angry about the traffic jam you are currently in (or about similar obstacles in your life),

- you get less upset about other people’s behaviour (especially at Corona times),

- you are less vulnerable to unobjective criticism and less easily offended,

- you are a good role model for your co-workers,

- you also contribute to the resilience of your organisation,

- and generally know better how to take good care of yourself and use your energies for the most positive future possible.

Notes (in German):

Gerne erzählt Ihnen Mario Hauff in einem Infogespräch mehr und findet bei Bedarf mit Ihnen heraus, wie ein optimales Training zur Verbesserung Ihrer Resilienz aussehen könnte. Unter https://www.angstlotse.de/ können Sie leicht Kontakt aufnehmen.

[1] Hirnforschung bestätigt: Es lohnt sich Sorgen zu machen

[2] Cognitive Bias Codex

[3] Eisbergmodell

[4] Bayer überlebt fast eine Woche in einer Gletscherspalte

[5] Samuel Koch: So geht es ihm 10 Jahre nach seinem Unfall

[6] Christian Peter Dogs: Wir finden einen Ausweg. Katastrophen sind lösbar!

[7] Linking Resilience Thinking and Transformative Change

[8] Das Hirnaufzugsmodell nach Gerald Hüther

[9] Building Organizational Resilience

Mario Hauff has published other articles in the t2informatik Blog:

Mario Hauff

Dipl.-Ing. Mario Hauff is the Angslotse. He guides individuals and organisations through difficult phases aggravated by fear and uncovers their potential with them. Like a nautical pilot he goes “on board” until “safe waters” are reached again and imparts self-efficacy and self-empowerment. After 20 years as an electrical engineer for microelectronics in an American company, he now offers individual and group coaching sessions, workshops and keynote lectures on growth in safety with state-of-the-art, scientifically sound findings.

“Why it works without fear”: You may stand at a canyon or in front of the photo wallpaper of a canyon.