Decision-making techniques for self-organised project teams – Part 3

For self-organised project teams it is important to know and use decision-making techniques. After the first part of my series of articles dealt with the question of how to find the right technique for a decision and the second part dealt with the influence of values and principles on decisions, part 3 is about decisions in the VUCA world. This time, too, I will present three concrete decision-making techniques.

Permission for decisiveness and thinking differently

What does “making decisions” mean in a self-organised project team in a VUCA world where complexity and ambiguity prevail? The term VUCA stands for

- Volatility/unstability/jumpiness

Continuous changes that cannot be predicted and the associated risks, disruption of markets, business models but also values. - Uncertainty/lack of validity

Many new numbers, data and facts do not help to make a decision because there is rarely a linear relationship in the complexity. No experience exists yet for the new knowledge. - Complexity

Totality of all interdependent characteristics and elements that are in a diverse but holistic set of relationships (system). - Ambiguity

Ambiguity of an issue, of a requirement description or “only” of linguistic expressions.

As much as this VUCA world confuses us, it also gives us the opportunity for innovation and creativity – for thinking differently. If the project team accepts this thinking differently and learns that decisions move them forward because decisions are never wrong, but as the term misdecision says, they are only “missing” something, the project team members can also feel comfortable in the VUCA world.

Reality versus VUCA

In project teams, it is not uncommon to find attitudes that focus on safeguarding in the sense of provability and justifiability of decisions made. These defensive attitudes, in which only well-founded solutions are targeted, prevent innovation and ultimately generate high costs because project teams only make decisions that are 100% justifiable.

This contrasts with the reality of the VUCA world, which requires a competent approach to uncertainty. There are not the usual clear figures, data and facts. As a consequence, the hedging mode we are so familiar with must be reversed, as it were, into a culture that values mistakes positively. Courage is therefore required, courage to take gaps and, in general, courage to make decisions.

Decisions that do not take risks, that are meant to prevent failure, prevent innovation.

Decision-making techniques are tools

To master this VUCA world, project teams need methods and tools. Decision-making techniques can help to structure the VUCA world and define processes and thus better deal with complexity.

Decision-making techniques …

- facilitate the approach to problems and decisions.

- often create clarity.

- reduce errors if necessary! But they are no substitute for

+ critical reflection on the plausibility of the methods with regard to their effect and function.

+ heeding spontaneous inspirations and intuitive impulses.

In addition, before applying or selecting methods, it is indispensable to answer the question: To what extent does this method help me to solve my decision problem?

To answer this question it is necessary to

- formulate a precise question or problem and

- check the appropriateness of the method.

The questioning influences the handling of the decision

Whether someone sees the glass half full or half empty is proverbial. In the same way, decisions are influenced by which aspect, the opportunity or the risk, is emphasised.

The following example will illustrate this:

- One in five companies fails to introduce this technology (risk).

- We have an 80% chance of getting the technology to work (opportunity).

In the same way, arguments and counter-arguments can be played off against each other:

- Those in favour of an alternative formulate it positively.

- Those who are against it focus on the damage.

Let the following examples sink in and check which argument would be valid for you:

- If we introduce the project now, we will achieve a turnover of one million euros in the first year.

- If we introduce the project now, we increase our total turnover to six million euros (without it, it is five million euros).

- The project introduction costs us only 500,000 euros.

- The project introduction still costs us 500,000 euros.

- The project costs remain stable at one million euros if we do without this project introduction.

- With this project budget we invest in future profit.

When preparing decisions, the project team should pay special attention to how the decision question is posed, which aspect is emphasised and from which reference point the consequences are compared. The following points should be considered:

- The decision question should be posed and questioned in different formulations.

- The question should formulate the positive and negative aspects in an equal and fair way.

It is not only the limitations of one’s own thinking and judgement that can lead to wrong decisions. Sometimes it is also framework conditions that make a decision-making situation unnecessarily difficult.

In the decision-making process, for example, the problem arises that decisions are not based on the facts themselves, but are made because – supposedly or actually – time is pressing. It is therefore all the more important for project teams to choose a decision-making technique that corresponds to the question, the time pressure and, if necessary, also the personal and/or project team motives.

Three more decision-making techniques for complicated and complex decisions

In the Cynefin model you will find a total of 21 different decision-making techniques (please see Part 1 of the series of articles). In the following, I will describe three more decision-making techniques in detail. These belong to the categories complicated and complex:

- Consensus (complicated)

- 6 Thinking Hats (complex)

- Systemic Consensus Building (complex)

Further explanations of the next decision-making techniques will follow soon in other blog articles.

Consensus

Benefit:

Making decisions collectively.

Objective:

With consensus, the project team as a whole makes the decision. No project team member has an objection and no one vetoes the decision. Everyone is comfortable with the decision.

Application:

So consensus looks at the veto, at the opposition. The typical questions in decision-making processes change. Instead of asking, “Who is in favour?”, it asks, “Does anyone have a veto?”. Instead of asking, “What is the best, perfect solution?” it is asked, “Is this solution workable and good enough for us?” The project team opts for the first-best solution instead of striving for the greatest possible maximisation of benefits. It has been shown that in complex or chaotic systems it is not useful to look for the perfect, benefit-maximising solution. Often, the benefit of finding a workable solution quickly is higher than striving for perfection.

A decision by consensus means that

- no one has an objection.

- one person shares the decision responsibly if he or she decides not to veto it.

- the decision is ok for everyone.

Procedure:

In order to reach consensus in a group, all persons must have the opportunity to express their objection to the decision. Therefore, when decisions are made according to the consensus principle, the position of the individual project team members is usually graded and recorded more precisely:

- The project team member stands behind the decision and fully supports it.

- The project team member supports the decision but expresses reservations, which are recorded.

- The project team member abstains, leaves the decision to the others and supports it.

- The project team member cannot support the decision, but expresses serious reservations which must be recorded. However, he or she refrains from making a formal objection so as not to hinder the group’s ability to make decisions.

- The project team member stands aside. He can neither agree nor support the proposal. However, he does not want to block and therefore stands aside.

- The project team member raises a formal objection to the decision, i.e. vetoes it.

If the last point applies to even one group member, then there is no consensus in the group. This means that the decision may have to be reworded or made anew.

Example:

There is a joint board (online or face-to-face). All issues that influence the decision are visualised on the board. In addition, proposals (alternatives) are developed. This is followed by a vote. Each project team member can veto a decision, but not all have to agree.

Project team members who do not cooperate in the development of alternatives or abstain from voting are considered a positive sign (agreement).

6 Thinking Hats

Benefit:

Creativity technique to make decisions in project teams.

Objective:

The 6 thinking hats method is a creativity technique to look at a decision from different angles (hats) in a project team. It was first introduced by Edward de Bono in 1985.

Application:

Decisions can usually be considered from different perspectives. Each point of view has its own value and brings new facets to the discussion. Pros and cons as well as quality and quantity of the decision-relevant contents increase and enrich the process of issue clarification. Each of the 6 hats represents with its colour a certain way of thinking, from emotional, optimistic to critical thinking.

The six hats stand for different perspectives, which are given different colours to distinguish them:

- White hat – stands for numbers, data, facts, is factually neutral and objective.

- Red hat – symbolises intuition, feeling, intuition and emotions.

- Black hat – stands for pessimism, difficulties, problems and dangers.

- Yellow hat – stands for optimism and opportunity thinking, forward thinking.

- Green hat – stands for creativity, lateral thinking, change.

- Blue hat – stands for overview, summarising, concluding.

Procedure:

- The problem is clearly defined and a question is derived.

- Coloured hats or other symbols are distributed to the participants.

- Each participant strictly adheres to his or her role.

- The blue hat can steer the process and chair the hat team.

- Each “hat” presents its arguments from the point of view of the “hat”.

- At the end of the discussion, the results are summarised and a decision is made on how to proceed.

The distribution of roles gives direction and dynamics to the clarification process. It stimulates creative ideas and yet disciplines the course of the discussions in the project team. In the case of very complex decisions, 6 rounds of argumentation can be conducted. In this process, the hats are passed on to the next project team member in each round. To remind each project team member of the colour of his or her hat, colour cards, headbands, etc. can also be used.

Example:

Of course, not every participant has to wear a hat (even though it would be fun). Wristbands or simply coloured cards are also fine.

The facilitator can deliberately steer the discussion and ask for “red” or “white contributions”.

It is useful to have strategies for deadlocked discussions in advance – just in case.

The method can also be used differently with a little routine: Everyone wears all six hats and announces their contribution by naming the hat colour.

Systemic Consensus Building

Benefit:

Finding the highest possible common denominator in a decision.

Objective:

Systemic consensus seeking aims to achieve the greatest possible consensus between all participants in decision-making processes in project teams.

Application:

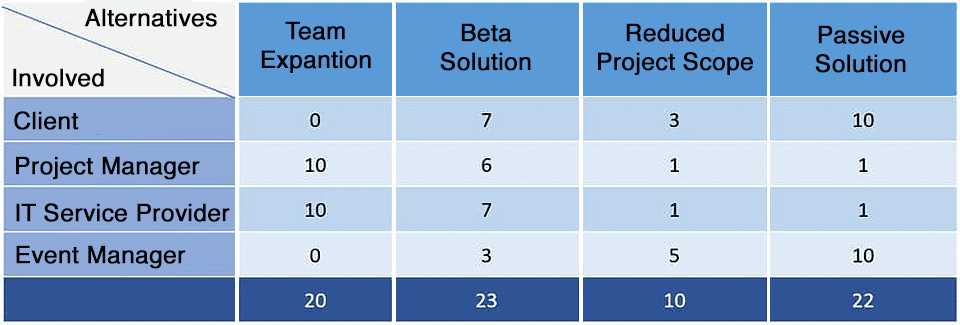

“Consensus building” is a made-up word derived from consensus and refers to the process by which a consensus view is reached. In this process, the project team identifies from a set of proposed solutions the one that is least rejected by all project team members. The core of the method is a resistance matrix, which is used to determine the extent of the project team members’ resistance to each proposal. Systemic consensus building is based on the assumption that the solution with the least resistance is more in line with the team consensus than the solution with the greatest agreement.

Procedure:

1. Formulate question for decision-making.

+ Describe the problem.

+ Collect and exchange information.

+ Desire of the project team members for a good solution.

2. Communicate the parameters for decision-making..

Possible question:

“What happens if two proposals get the same score?”

Possible rule:

Proposals with 10 points of resistance from one of the project team members will not be taken under any circumstances.

3. Develop solution proposals with the project team members.

+ Collect as many solution proposals as possible (brainstorming).

+ Subsequently check the proposed solutions for suitability to solve the problem

4. Integration of a passive solution.

This is a proposal that does not involve any change to the current situation. There are cases where no change has the least resistance from the group members.

5. Evaluation of the proposed solutions / voting by resistance scores.

The project team members assign individual resistance points. Zero stands for no resistance (greatest acceptance), ten resistance points show that someone does not support the proposal at all. The passive solution is also evaluated. The evaluation is done with the help of a matrix.

6. In the matrix, all points per column are added up. The proposal with the smallest value is the one with the least resistance. The value for the passive solution serves as an indicator of whether the change is supported.

7. In order to make more sense of the results, the project team members can now share with each other why their own suggestions have led to resistance from someone else.

“What does my suggestion need so that it doesn’t cause so much resistance from you?”

8. If necessary, the proposed solutions can be adjusted after this discussion and listed again for a resistance measurement with all project team members…

Example:

The project team consists of the following members and their wishes:

- Client – New website for the company anniversary.

- Project manager – A good solution should use the existing project team and not require new project members.

- IT service provider – A solution is good if there is no damage to the company due to poor service.

- Company anniversary event manager – A solution that can be integrated into the company anniversary programme.

The project team agrees on the question:

What do we change about the project to implement the best possible solution for the anniversary website?

The project team puts together four proposed solutions:

- Team expansion – integrate new project staff to meet the deadline.

- Beta solution – develop a beta version that will be touched up after the anniversary.

- Reduction project scope – Provide the web pages that can be made available in high quality by the company anniversary.

- Passive solution – Continue working at the same pace and announce website on company anniversary.

The proposed solutions (alternatives) are now evaluated in the resistance matrix. Each project team member can rate each solution. 0 points mean no resistance, 10 points mean high resistance.

Based on the result of the resistance matrix with the lowest resistance – Reduced Project Scope – an action plan can now be created.

Conclusion

In today’s VUCA world, it is hardly possible for project teams to make a decision that lasts for the entire project. The project team has to react quickly to changes without jeopardising the values and principles of the project/company. For this reason, it is important to know the different decision-making techniques and in which system (simple, complicated, complex or chaotic) they are usefully applied.

In this sense, use the Cynefin model to find the right decision technique.

Notes on the economics and psychology of decision-making:

Econometric models to hedge financial risks are not considered here, as business profitability aspects are the basis of the decision and project teams have no direct influence on them.

Similarly, I am aware that some of you are missing references to sociocracy, psychology and the like. I have purposely not gone into this as I have focused purely on decision-making techniques and will continue to do so.

My starting point for this series of blog posts are self-organised project teams that know and live their values and principles and are only lacking the tools at one point or another – in other words, the knowledge of the right decision-making technique for the corresponding issue.

Notes:

In the next part of the series, Cornelia Kiel will explain more decision-making techniques.

If you are interested in further background information on decisions, Cornelia Kiel recommends the following German books:

Gemeinsam Denken von Carolin Wolf, Business Village GmbH

Entscheidungen erfolgreich treffen von Martin Sauerland und Pater Gewehr, Springer

Die (Psycho-)Logik des Entscheidens von Walter Braun, Huber Verlag

Das Handbuch der Entscheidungen von Tobias Leisgang und Nadja Petranovskaja

Cornelia Kiel has published more articles in the t2informatik Blog:

Cornelia Kiel

Cornelia Kiel has been managing projects intelligently and sustainably for over 20 years. She uses a wide range of methods: from the waterfall to the V-model and the various agile frameworks such as Scrum, Kanban or SAFe – always in the interests of an efficient project.

Her clients benefit from her extraordinary wealth of experience as a project manager, ScrumMaster, AgileCoach, moderator and BVMW-certified consultant for medium-sized companies.

In the beginning there is always the question of why. – Even as a child she drove her father to despair with this. – With this curiosity, Cornelia Kiel will work with you to find out the meaning and purpose of your project. The question of the benefit for your customer is also answered. From this starting point, you will reach the goal of your project in a focused manner.