No one could have foreseen that

June 2024, Reichertshofen in Bavaria. Markus Soeder stands in front of the cameras wearing rubber boots and a blue rain jacket. Around him are flooded streets, houses and commercial buildings. The town was evacuated because the power had gone out. People lost their lives. The Bavarian Minister-President says: ‘No one could have predicted flooding and damage on this scale.’ [1]

A black swan? Economist Nassim Taleb uses this term to describe events that have three characteristics [2]:

- They are extremely rare and lie outside normal expectations.

- They have massive consequences.

- They only seem logical and predictable to us in hindsight.

But climate researchers have been warning for years about increasing extreme weather events. Bavaria had already experienced severe flooding in previous years. What happened in Reichertshofen was therefore anything but a black swan.

A good four years earlier, an even greater crisis befell us: COVID-19. Millions of people died, and a state of emergency prevailed for months. The first two characteristics of a black swan seem to be fulfilled. And yet, Bill Gates stood on the TED stage in Vancouver in 2015 and said: ‘If something kills more than 10 million people in the coming decades, it will most likely be a highly infectious virus, not a war. Not missiles, but microbes.’ [3] The WHO had also repeatedly warned of future coronavirus pandemics after SARS in 2003 and MERS in 2012. [4]

This pattern is also repeated in the corporate context. The year is 2000. In Dallas, Texas, Reed Hastings, the founder of Netflix, is sitting in the office of Blockbuster CEO John Antioco. Hastings offers to sell Netflix for $50 million. [5]

Antioco refuses. The idea seems absurd to him. Who would order DVDs by post when you could just drive to the shop? Streaming was the vision behind the name Netflix, but in 2000, the internet was not yet technically ready. Ten years later, Blockbuster filed for bankruptcy. Netflix is now worth over £300 billion.

These three examples have one thing in common. The phrase ‘No one could have seen that coming’ is wrong in all three cases.

Illuminating the future with a torch

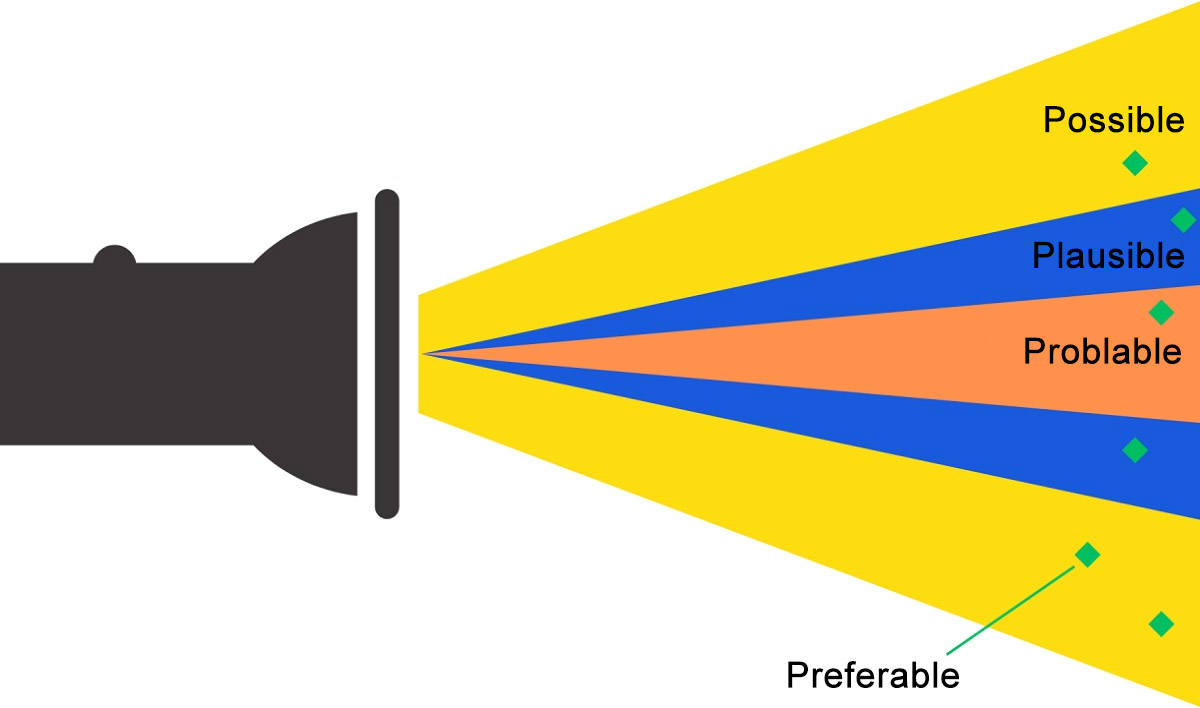

Do you remember the futures cone from the first part of my series on the future? Futurologist Joseph Voros uses the model to illuminate the future with a torch. [6] The further the beam reaches into the distance, the wider the cone becomes and the more possible futures become visible.

Figure: Futures Cone according to Joseph Voros

Part 1 also showed why our thinking often artificially narrows this cone. Linear thinking and mental shortcuts almost automatically direct our gaze to the narrow range of probable futures. The status quo bias makes it feel safer to continue optimising what already exists rather than building something new. The normalcy bias, in turn, ignores deviations as long as they are not clear and unambiguous. As long as something does not obviously deviate from the norm, we treat it as if everything is fine.

COVID-19 and the development of Netflix were outside this narrow beam of light for precisely this reason. They did not fit into the picture of what we considered likely. In the case of the floods in Bavaria, it is debatable whether they were at least on the edge of the probable future. In any case, it was not a complete surprise.

In the Christmas story ‘When the future appears at Christmas’, managing director Karl Meier receives a visit from Katie, the spirit of the possible future. She leads him to the outer edge of the cone of light. To where developments lie that seem less likely, but whose effects are enormous. Extreme weather floods the city centre. Former employees become radicalised. Machine breakers attack automated factories.

None of this is at the centre of what we expect. But it is visible in the cone of light if we are willing to move it further.

Probable, plausible or possible futures

The cone of light representing the plausible future is broader than that representing the probable future. This is the area in which classic scenario planning operates. The central question is: what happens if individual parameters change? New regulations, technological leaps or market shifts are systematically considered here. These futures are realistically conceivable and well-founded, even if they are not necessarily considered probable.

Even further out is the area of possible futures. Here we find developments with a low probability but potentially massive impact. Everything that is physically possible belongs to this outer cone of light of all futures. Even if much of it seems unrealistic today, it is not impossible.

Plausible and possible futures are not invisible. They send out weak signals. These are easy to overlook because they do not fit into our existing world view and contradict our assumptions.

Remember the managing director from the strategy day in Part 1? After my presentation on dark factories in China, autonomous robot taxis in California and AI-based construction planning, his comment was: ‘Great presentation, but pretty far-fetched, right?’ For him, these developments were outside his cone of light. Not because they were unthinkable, but because they did not seem relevant to him.

Three methods for making the possible visible

How can these weak signals be recognised? How can you train your eye to see the external cone of light? Below, I present three methods that can be applied immediately:

Method 1: Jane McGonigal’s ‘100 things that could be different in the future’

Futurist Jane McGonigal has developed an astonishingly simple brainstorming method. [7] It forces you to consciously break out of habitual thought patterns. The method consists of three steps.

- List facts. Choose a topic, such as work, mobility or shopping, and write down a hundred facts that apply to it today. The more banal and obvious, the better. It’s not about creativity, but about taking stock.

- Turn these facts on their head. Take each individual statement and reverse it. Imagine that in ten years’ time, the opposite will be true. Even if it seems unrealistic or even ridiculous at first.

- Look for clues. Ask yourself whether there are already signs of this reversal today. Are there places where it is already a reality? Are there technological, regulatory or social developments that point in this direction?

Let’s assume that the managing director’s company from Part 1 is active in the construction industry. What would such a list of 100 things look like? Which seemingly self-evident assumptions would be shaken?

| Fact | Different in 10 years… | |

| 1 | People are working on a construction site. | No people work on a construction site. |

| 2 | Site managers coordinate the work. | There are no longer any site managers. |

| 3 | A house has a roof. | Houses do not have roofs. |

| 4 | Families need space. | Families no longer need space. |

| 5 | Trees are being felled. | Trees are integrated into the construction. |

| … |

Trees integrated into buildings? Architect Stefano Boeri has integrated 800 trees, 5,000 shrubs and 15,000 plants into two residential towers in Milan’s ‘Bosco Verticale’. [9] And in Austin, Texas, one of the most comprehensive tree protection ordinances in the United States protects old trees from demolition. [10]

Method 2: Thinking through multiple futures using scenario planning

The scenario planning technique developed by Kasow and Gaßner combines key influencing factors to create different visions of the future. [11] It helps to consider several possible developments in parallel and to reveal blind spots in one’s own thinking.

The first step is to define the area of investigation and the time horizon, followed by the identification of key factors that will significantly shape the future of this area. In our example in the construction industry, these could be materials, economic conditions, technological developments and the availability of skilled workers.

The next step is to analyse how these factors could develop. Consistent scenarios emerge from the different characteristics. Alternatively, scenarios can be defined first and then the factor developments that would fit them can be derived.

The following example uses three of Jim Dator’s ‘Four Futures’ [12]:

- Continuation: Growth and change continue largely as before. There are no fundamental system breaks.

- Limits and Discipline: Societies and companies adapt to regulatory and ecological limits. Stricter requirements force change and sacrifice.

- Transformation: Disruptive technologies or new business models fundamentally change the rules of the game and challenge existing structures.

The strength of scenario planning does not lie in predicting the right future. It lies in being able to think about several plausible futures at the same time and make decisions more robust.

| Continuation | Limits and Discipline | Transformation | |

| Materials | Concrete and steel continue to dominate | Circular economy mandatory, regional materials required | Construction botany, fungal mycelium, 3D-printed biomaterials are standard |

|

Economic conditions |

Moderate growth, rising construction prices | High CO2 taxes, strict ESG requirements for financing | Modular construction democratises building, costs fall by 50% |

| Technology | BIM becomes standard, easy digitisation | AI-supported planning for climate resilience mandatory | AI plans and coordinates, robots build autonomously |

| Availability of skilled workers | Slight shortage, higher wages | Retraining in sustainable construction methods promoted | Robots replace 60% of manual labour |

Method 3: ‘Kill The Company’

‘Kill The Company’ is a deliberately provocative exercise devised by innovation consultant Lisa Bodell. [13] It forces companies to recognise their own weaknesses before their competitors do.

The starting point is a simple but uncomfortable question: ‘If you were our competitor with unlimited resources, how would you wipe us off the market?’

In the exercise, teams are allowed to symbolically ‘kill’ their own company. They develop targeted disruptive strategies that could destroy the existing business model. The change of perspective is crucial. The focus is not on defence, but on attack.

What might have emerged from a ‘Kill The Company’ workshop at Blockbuster? Would it have been possible to identify some of Netflix’s later killer features? And what would be the killer strategies for a medium-sized company in the construction industry?

Weak signals can then be sought again for the identified points of attack. Perhaps there is already a start-up somewhere in the world that is addressing precisely one of these points. Still small, still inconspicuous, but with the potential to fundamentally change the market.

No guarantee for the future, but a pair of glasses that broadens your view

These methods are no guarantee against disruption. They are no assurance that companies will automatically do the right thing or react in time. And they certainly cannot predict the future with any accuracy. But they do provide a pair of glasses that broadens your view.

Instead of staring at the narrow beam of light that is the most likely future, they reveal several possible futures. They help us to perceive the outer edge of the beam of light and to consider developments that would otherwise be easily overlooked.

Recognising weak signals, thinking through scenarios, consciously challenging your own business model. All of this shows what might lie ahead. Above all, however, it removes the convenient protective function of the phrase ‘No one could have forseen that.’ Because much is visible long before it happens, if we are willing to look.

The crucial question remains unanswered, however: What future do we actually want?

Notes (partly in German):

This is part 2 of a series of articles by Tobias Leisgang about the future. Part 1 dealt with the dangers of a probable future. Part 3 deals with desirable futures and methods that companies can use not only to react, but also to work specifically towards the future they want.

Tobias Leisgang is a moderator and coach for companies that want to boldly break new ground. If you’re still finding it difficult to get started, feel free to visit his website or contact him on LinkedIn to take the first few steps together. 😉

On 20 and 21 March 2026, Tobias Leisgang and the Bamberg ambassadors of the Ministry of Curiosity and Future Enthusiasm invite you to the second Camp fuer Neugier und Zukunftslust. In the beautiful Bergschloesschen with its breathtaking view over the World Heritage city of Bamberg, participants can look forward to a weekend that awakens curiosity and ignites enthusiasm for the future.

[1] Compact: Wieso wir das Hochwasser voraussehen konnten

[2] Wikipedia: Der Schwarze Schwan

[3] TED: Bill Gates – The next outbreak? We’re not ready

[4] Spiegel Wissenschaft: WHO sieht Erreger als Gefahr für die ganze Welt

[5] Galaxus: Netflix vs. Blockbuster: Untergang eines Imperiums – wegen 40 Dollar

[6] The Voroscope: The Futures Cone, use and history

[7] Amazon: Jane McGonigal: Imaginable: How to See the Future Coming and Feel Ready for Anything―Even Things That Seem Impossible Today

[8] US Department of Energy: Efficient Earth-Sheltered Homes

[9] Stefano Boeri Architetti: Vertical Forest Milan

[10] Forest in Cities: Protecting the Urban Forest Through Tree Preservation and Land Development Regulations in Austin, Texas

[11] ResearchGate: Hannah Kosow und Robert Gaßner: Methoden der Zukunfts-und Szenarioanalyse Überblick, Bewertung und Auswahlkriterien

[12] IESE: 4 scenarios to imagine the future

[13] Campus: Lisa Bodell: Kill the Company

Would you like to discuss the challenges of the future as a multiplier or opinion leader? Then share this post in your networks.

Tobias Leisgang has published additional posts on the t2informatik Blog, including:

Tobias Leisgang

‘The future is the only place I’ll spend the rest of my life’ – Charles Kettering was right and Tobias Leisgang takes this quote very seriously. After studying electrical engineering, he developed semiconductors, researched the latest technologies with global teams and made the supply chain of an automotive supplier fit for the future.

Today, he helps small and medium-sized companies develop sustainable business models – with a great deal of foresight and a dash of pragmatism. Because there are often many decisions to be made between good ideas and their implementation – and that’s exactly where Tobias comes in: in ‘Kopf & Bauch – Der Podcast der Entscheidungen’, he provides exciting insights into how to make them.

And because standing still is not an option for him, Tobias continues his journey as a future shaper – not in a fancy suit, of course, but as a student in the future design programme. After all, who says you can never learn enough?

In the t2informatik Blog, we publish articles for people in organisations. For these people, we develop and modernise software. Pragmatic. ✔️ Personal. ✔️ Professional. ✔️ Click here to find out more.