Learning is not a sexy subject. Or: Learning from Scotty.

Learning is not a sexy subject. A colleague recently told me this, who had looked at the statistics of his company blog. In the click comparison, topics such as agility, leadership or digitalisation almost always win. Learning probably reminds us of our school days, of grades and the often thwarted joy of new knowledge. And yet I would like to devote myself to this topic here. Precisely because it is not sexy. Or maybe it is, if you look at it from the perspective of science fiction.

A conscious counterpoint

Glad you’re still with me. You may have noticed that I just wrote, “…learn in unexpected situations…” You know, they say that you “learn from situations.” I deliberately set a counterpoint here: You actually learn IN unexpected situations by doing, and that may, even must be fun. Otherwise it won’t work. Neuroscientists have now discovered that pleasure – thanks to the messenger substances it involves – is an important ingredient, almost a prerequisite for sustainable learning.

I would like to introduce you to the setting in which the apparent contradiction, namely learning with fun in UNEXPECTED situations (which we often regard as unpleasant) is resolved. The crew of the starship Enterprise seems to me a suitable example, because “These are the voyages of the starship Enterprise. Its five-year mission: to explore strange new worlds. To seek out new life and new civilizations. To boldly go where no man has gone before!”

Scotty and the starship Enterprise

Let’s take a look at how Engineer Scott, known to everyone as Scotty, acts and learns in the “unknown”.

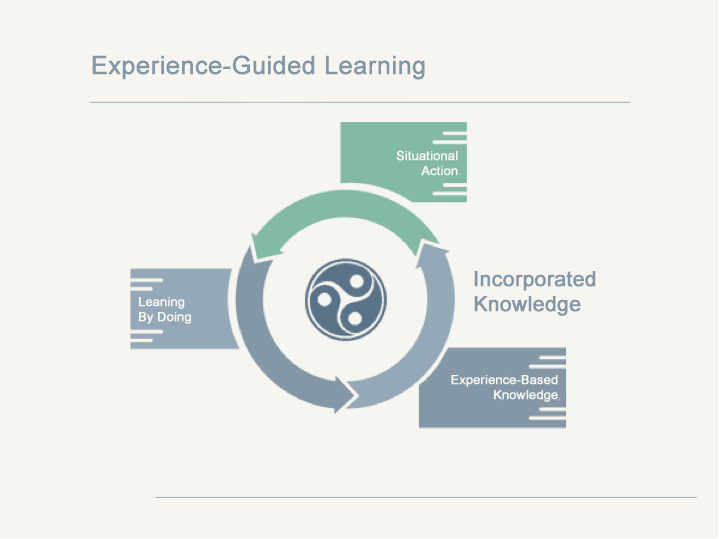

If the drive system fails unexpectedly and for some unknown reason, he’ll feel his way to solving the problem. He reacts quickly and interlocks his actions and decisions (situational action). In doing so, he relies on his intuition, which provides him with new solution impulses. Every attempt at a solution becomes a learning experience (learning by doing), which increases his experience-based knowledge base. And he continues to do so until success is achieved – which he often “feels” through his sensory organs (noise, vibration, temperature, …).

Of course Scotty also has a profound knowledge in the classical sense. He is excellently trained in drive technology and is therefore what we like to call an expert; expertise is an important prerequisite for intuition appropriate to the situation. And Scotty also shows us how to maintain the fun of learning new experiences, even under difficult conditions.

And now to the theoretical background:

What is an unexpected situation?

Again and again we experience situations in which something happens that we did not expect. We are usually irritated and often react unconsciously, based on long practiced behavior patterns. In the beginning there is often a shock or at least an astonishment. Many people freeze, others start immediately and super active.

The situations themselves are unpleasant for most of us – we lose control – and so we try to avoid them. We plan, we increase our knowledge, we control closely, we use all our cognitive skills. And already we are in the middle of what we already know from school: Rational action, targeted action to achieve our goals. Unfortunately, such an approach is neither helpful nor appropriate for unexpected situations.

Many people actively rely on prevention strategies, a typical example being risk management methods. And this is not wrong, on the contrary, we avoid the expected unexpected, but they are not prevention but rather reduction strategies. However, since the future is not predictable, unexpected events occur. These are essentially new, and learned “book knowledge” is of limited help.

How to take appropriate action in these situations

Prof. Böhle from the Institute for Social Science Research in Munich has been researching for decades on the topic of “acting in uncertainty” and also how to learn in such situations. The magic word is: experience-based knowledge.

Unexpected situations are characterised by the fact that we do not know what to do and are often accompanied by (time) pressure. The solution strategy lies in a step-by-step approach and trial and error, so to speak. Each of these attempts – called situational action in science (with Scotty as a prime example) – leads to new experiences and thus new knowledge, regardless of whether the attempt is successful or not. Practically speaking, we learn while doing. And with this newly acquired knowledge, we then move on to the next round of trial and error, until a situation arises which we regard as a solution.

The resulting knowledge is also called “incorporated”. This describes that this is not our rationally accessible knowledge, but one that can be assigned to body intelligence. The access to the experience-based knowledge is rather not rational, situational acting is based on what we like to call intuition.

Practising helpful skills

And what does each of us need in order to proceed like Engineer Scotty and, above all, to have the necessary fun? The answer is simple, but its implementation in practice is not: We have classic knowledge and experience, use it intuitively in the situation and thus expand our experience-based knowledge.

And how does that work?

Since the concrete situation and the necessary competencies are not known in advance, we need higher-level (meta-)competencies instead. These need to be trained in advance so that we can automatically fall back on them in the unknown situation – similar to professional footballers.

In terms of developmental history, we have had these meta-competencies since birth. Small children have great joy in trying things out and do not give up prematurely. Just think of children who learn to walk: they gurgle with joy, falling over is part of it, with every fall over they gain experience and learn a little more – until they can walk. It is this early childhood attitude and the associated skills that help us in unexpected situations.

However, most of us have forgotten them because they are not encouraged in our living space, but tend to be trained down. Even children are often not only deprived of the joy of trying things out, but also the mindful body awareness, which is important for intuition, is hardly encouraged. Seriously meant tolerance of mistakes and playful joy are also rather rare among adults in professional contexts. These necessary meta-competences need to be (re)awakened for unexpected situations and trained sufficiently.

This is not an easy way, because we have practiced for years to replace the playful joyful approach with a more cognitive approach. And so we are good at planning and rational procedures and would therefore like to approach the learning of intuition cognitively. That does not work.

But there are training fields in which we can acquire meta-competencies. Such a training field would be, for example, per se the rediscovery of our natural abilities for joyful experimentation. Try to rediscover the joy of (professional) trial and error and in doing so learn more about yourself, your possibilities and also your limits: How does something succeed, how does something fail? What (and which emotions or beliefs) prevent it from succeeding? What promotes success?

Of course, wrong ways are allowed and even welcomed. Discovering new facets within us can be really fun, curiosity about oneself is helpful. We bring the necessary expertise with us, because who, if not each of us, is an expert of his or her own? In this way, you gain experience and get to know your possibilities better; a further prerequisite for remaining capable of acting in unexpected situations. At the same time, you will train the meta-competencies mentioned above.

Being able to do this is an essential core competence in a time that is characterised by the complexity and obscurity of problems. This gives you the prerequisites to act appropriately instead of endlessly and mostly under time pressure debating solutions and plans. And it is also fun, because it corresponds to our childlike and playful approach.

Finally, a note: When you practice or experience unexpected situations, please do not slavishly stick to set goals. Intuition also helps to identify opportunities and needs for innovation and change in such situations… but this is worth another blog article.

Notes:

Astrid Kuhlmey has published more articles in the t2informatik Blog, including

Astrid Kuhlmey

Computer scientist Astrid Kuhlmey has more than 30 years of experience in project and line management in pharmaceutical IT. She has been working as a systemic consultant for 7 years and advises companies and individuals in necessary change processes. Sustainability as well as social and economic change and development are close to her heart. Together with a colleague, she has developed an approach that promotes competencies to act and decide in situations of uncertainty and complexity.