Leadership and individual resilience

Beyond the common but often simplified statement in the advice literature that everyone is personally responsible for improving their individual resilience because it can be trained, this paper is particularly concerned with the applicability and effectiveness of the concept in a work (environment) world that can be described with the VUCA term. In concrete terms, one of the central questions is therefore: What contribution can a company make from a leadership perspective in order to strengthen the defensive and adaptive powers of employees in the face of increasing psychological stress at work?

Resilience – a multi-layered term

Resilience means something like tension, elasticity, durability and originally comes from physics (material science). There it characterises the property of a solid material to regain its original shape after an external impact that temporarily changes its form.

In relation to humans, there are a large number of definitions of the term, all of which essentially aim to describe the handling of psychological stress, but emphasise different aspects. On the one hand, resilience is understood as “the ability (…) to master crises in the life cycle with recourse to personal or socially mediated resources” (Welter-Enderlin/Hildebrand 2006). If the processual character of the term is to be clarified, resilience also refers to “the maintenance and restoration of mental health during or after stressful life events” (Leibniz Institute for Resilience Research, no year).

It should be noted here that it is not the critical life events themselves, which can be “typical biographical changes (…) or traumatic experiences” (Pschyrembel Online, no year), that cause a crisis: rather, what is decisive is “how those affected evaluate the events on the one hand and their abilities to cope with the situation on the other” (Siegrist/Luitjens 2018). If an event is assessed by the affected person as threatening and an appropriate reaction appears impossible, this triggers a psychological crisis.

Resilience is thus reflected in the way a person adapts to a psychological stress or its negative stress consequences, but not in a general lack of crisis experience.

The coping response to a mental crisis by people with high resilience is characterised by the fact that either performance is restored more quickly or performance is maintained to a greater extent and does not drop as much as in the normal course.

Numerous scales are available for measuring and recording resilience, which use different criteria and often a seven-point Likert scale (from 1: “I disagree” to 7: “I completely agree”) for answering the questions (Rolfe 2019). It should be critically questioned to what extent the various measurements are suitable for determining individual resilience before and after a crisis if the questions are strongly focused on positive personal characteristics.

Resilience models

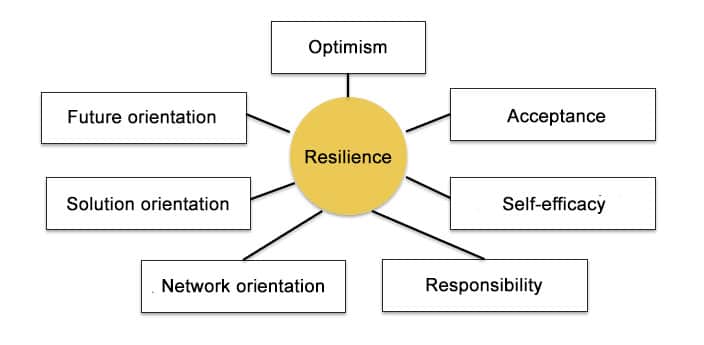

Different resilience models are used in the literature, which draw on various factors to establish strong defences against stressors and critical life events. The 3 + 7 model according to Heller (2019) draws on the classic resilience keys, which concern the cognitive dimension, the behavioural dimension and the contextual dimension.

7 Resilience keys according to Heller (2012)

These are expanded to include the three factors: Mindfulness, Tolerance of Uncertainty and Willingness to Change, “which provide a reflective framework for identifying approaches to strengthening resilience” (Heller 2019) and are relevant against the backdrop of changing conditions in a volatile, uncertain, complex, ambiguous environment. The transformation of gainful employment can be described in this perspective using the keywords: digitalisation, acceleration, competition and subjectification (Hurtienne/Koch 2018).

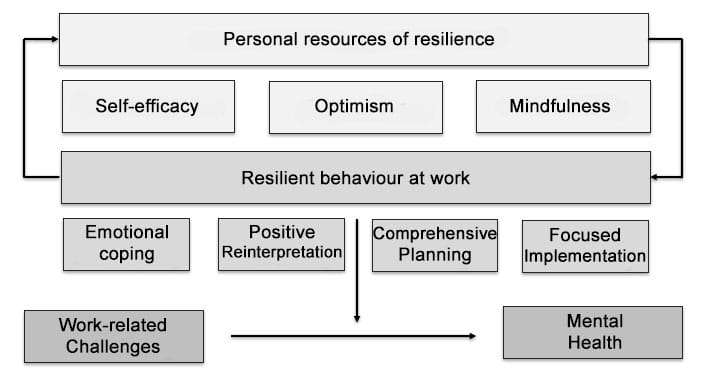

Soucek et al. (2016) have developed a model for the work context at the level of individuals that distinguishes between personal resources and individual behaviour at work, but combines them in an integrated view.

The personal resources self-efficacy, optimism and mindfulness promote resilient behaviour at work with the four facets:

- Emotional coping,

- positive reinterpretation,

- comprehensive planning and

- focused implementation

and together contribute to overcoming work-related challenges and to mental health.

Training and contextuality

It is undisputed that resilience can be trained in principle. The proportion of individual resilience that is determined by personality and can be described as “raw resilience” (Draht 2018), which is difficult for the individual to access and change at will, is probably at least 30 percent (Gilan/Helmreich 2021). To be distinguished from this is “acquired resilience” (Draht 2018) as a combination of self-awareness and self-control. A large number of simplified, target group-unspecific training offers with a promise of self-optimisation remain fundamentally at the level of personal protective factors of individuals and deliberately fade out externally determined and personally uninfluenceable framework conditions.

In order to grasp the life background of people as a whole, the work-related contextual factors and the psychological stresses emanating from them must also be taken into account. Psychological factors of workload can basically be assigned to the four thematic fields of

- work task,

- working time,

- technical factors and

which interact with each other. The specific working conditions act either as stressors or resources, which have negative (stressors) or positive (resources) effects on the working person in the short term and impair or stabilise mental health in the longer term.

“Today’s working world is characterised by high and changing demands that endanger the mental health of employees” (Soucek et al. 2016). Therefore, in addition to imparting knowledge and personal strategies for dealing with crises, the possible levers of a company to promote the resilience of employees must also be considered. It is assumed that individual resilience can be influenced by organisational structures and that changes in the framework conditions that determine the provision of gainful employment in companies increase the resilience of employees (Soucek et al. 2016). From the point of view of organisational psychology, there are a number of approaches to help employees better cope with existing workloads and their negative effects in terms of strengthening individual resilience. Leadership is a key factor influencing the mental health of employees.

A leadership issue

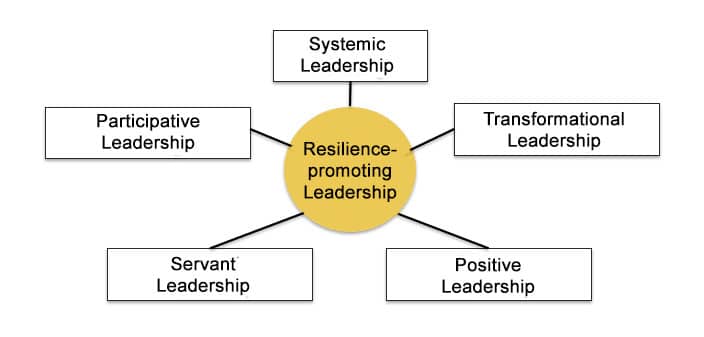

It is discussed that “laissez faire leadership” and “autocratic leadership” can have fundamentally negative consequences on the health of employees, while various other concepts of leadership can stabilise the resilience of employees and reduce the impairment of their well-being.

From the perspective of positive psychology, resilience-promoting leadership is influenced by several leadership concepts.

Leadership concepts influencing resilient leadership according to Rolfe (2019)

Since Rolfe (2019) rightly emphasises overlaps in the content of individual leadership concepts mentioned above and points out that resilience and agility influence each other, VOPA+ should be added here “as an adequate leadership culture in the digital age” (Petry 2016): Leaders trust employees, create networks, are open to ideas, anticipate necessary adjustments, act flexibly and proactively (agility) and enable participation in decision-making processes (participation).

Irrespective of a reference to individual leadership concepts, it can be stated: “Resilience-oriented leadership sees the whole person with all their strengths and limitations and strives to address the various basic neurobiological needs of a person as individually as possible” (Draht 2018). The aim is to create trust and identification and to ensure that employees perform well in the long term without having to operate permanently at their limits. Leadership behaviour has an impact on the health of employees if it succeeds in adequately taking into account their basic psychological needs for bonding/belonging, orientation/control, self-esteem enhancement and protection, and pleasure acquisition and displeasure avoidance (Grawe 2000). If employees are resilient, this ultimately has a positive effect on both performance and health.

Based on a dynamic way of thinking and a corresponding mindset (Hofert 2018), managers have the task of ensuring the presence of those factors that strengthen the resilience of employees. The options for action outlined here can be applied regardless of the size of the company or the sector to which it belongs.

Concrete possibilities for action for resilience-oriented leaders

Act as a role model in dealing with own emotions and resources:

- Leaders are aware of their role as role models and regularly put themselves to the test with regard to their individual resilience (reflection).

- They strengthen their self-leadership (mental and emotional) as an interplay of self-awareness and self-control.

Convey meaning and orientation:

- Leaders provide orientation and ensure that options for action are understood in order to strengthen the self-efficacy of employees. They convey meaning, communicate the purpose and vision of the company and thus create the prerequisite for motivation and the emotional commitment of employees.

Strengthen autonomy:

- Managers strengthen the personal responsibility and self-determination of employees through autonomous decision-making.

Strengthen trusting relationships:

- Leaders act according to the principle of “trust breeds trust”. They act reliably, openly and compassionately to foster relationships with staff.

Strength orientation:

- Managers recognise the diversity of employees and their potential. They recognise the individual talents of employees and use their strengths prudently.

Successful communication:

- Leaders communicate at eye level and ensure transparency. They cultivate unprejudiced listening and openly address their own non-knowledge and regularly give and take feedback.

Appreciation:

- Leaders use the ‘language of appreciation’: undivided attention, helpfulness, gestures that touch, strengthening and appreciative words, physical touch (current limits due to Corona pandemic).

Fairness:

- Leaders ensure distributive justice (outcome fairness), procedural justice (process fairness), informational justice (information fairness) and interpersonal fairness (dealing with each other).

In order to sustainably anchor individual resilience in companies, in addition to resilience-oriented leadership, structures and processes such as effective occupational health management, a constructive culture of error and future-oriented personnel development are needed to effectively buffer possible mental stress at work.

Conclusion

Managers should develop a positive-realistic understanding of resilience from a critical perspective: Although individual resilience is not a panacea for all people or in every personal stress situation, it is gaining in importance against the backdrop of a dynamic and complex working world.

In addition to the targeted teaching of resilience-promoting strategies, leadership is needed, i.e. leadership instead of management, in order to strengthen the individual resilience of employees in companies. Especially in a time when more resilience is demanded and sometimes also promoted, we are all called upon, as Graefe (2019) writes, “not to adapt and resign ourselves to the world we live in, but on the contrary to insist that we can change it – not because we are completely sovereign and rational or because we are exposed, powerless and ignorant, but because we are both: autonomous and dependent, vulnerable and yet capable of action, ignorant and rational”.

Notes:

Stephan Pust conducts specific resilience seminars for organisations, knowledge workers and their managers. You can find details at https://tbt-pust.de/.

Literature:

Draht, Karsten (2018): Die resiliente Organisation.

Gilan, Donya, Helmreich, Isabelle (2021): Resilienz die Kunst der Widerstandskraft. Was die Wissenschaft dazu sagt.

Graefe, Stefanie (2019) Resilienz im Krisenkapitalismus. Wider das Lob der Anpassungsfähigkeit.

Gunkel, Ludwig et al. (2014): Resiliente Beschäftigte. Eine Aufgabe für Unternehmen, Führungskräfte und Beschäftigte.

Heller, Jutta (2012): Resilienz. 7 Schlüssel für mehr innere Stärke.

Heller, Jutta /Gallenmüller, Nina (2019): Resilienz-Coaching: zwischen „Händchenhalten“ für Einzelne und Kulturentwicklung von Organisationen.

In: Heller, Jutta (Hrsg.) Resilienz für die VUCA Welt. Individuelle und organisationale Resilienz entwickeln.

Hofert, Svenja (2018) Das agile Mindset. Mitarbeiter entwickeln, Zukunft der Arbeit gestalten.

Hurtienne, Jörn / Koch, Katharina (2018): Resilienz.

In: Karidi, Maria et al. (Hrsg.) Resilienz. Interdisziplinäre Perspektiven zu Wandel und Transformation.

Kals, Ursula (2020): Was sollen Führungskräfte in der Krise tun?

In FAZ: https://www.faz.net/aktuell/karriere-hochschule/buero-co/was-sollen-fuehrungskraefte-in-der-corona-krise-tun-16714466.html (access December 2021)

Leibniz-Institut für Resilienzforschung Online (o.J.): Stichwort Resilienz. https://lir-mainz.de/resilienz (access December 2021)

Petry, Thorsten (2016): Digital Leadership. Unternehmens- und Personalführung in der Digital Economy.

In: Petry, Thorsten (Hrsg.) Digital Leadership.

Pschyrembel Online (o.J.): Kritische Lebensereignisse. https://www.pschyrembel.de (access December 2021)

Rolfe, Mirjam (2019): Positive Psychologie und organisationale Resilienz. Stürmische Zeiten besser meistern.

Siegrist, Ulrich / Luitjens, Martin (2016): Resilienz

Welter-Enderlin, Rosemarie / Hildebrand, Bruno (2006): Resilienz. Gedeihen trotz widriger Umstände.

Stephan Pust has published more articles in the t2informatik Blog, including:

Stephan Pust

Stephan Pust was an IT executive for a long time. Today, as a freelance trainer and consultant, he supports managers in organisational change and as a driving force for change in the new world of work. He also benefits from his extensive experience as a process manager. In addition, he works as a lecturer for various universities in Niedersachen, Germany in order to pass on his professional and personal experience to future specialists and managers.