Kamishibai and Kanban for (too) interdisciplinary teams

Interdisciplinary teams are almost per se considered good these days. However, this usually only refers to the professional interdisciplinarity with regard to the respective knowledge, not to that in the concrete work task. The latter, however, is much more common – and can cause a lot of problems: First of all, it may sound good to distribute development, support and maintenance, for example, among all the people in the team on an interdisciplinary basis, leaving everything in one hand – even if this is often only unavoidable and due to a lack of dedicated positions. In practice, however, this approach presents the people in the team with challenges with a great potential for conflict; without a very good work organisation, the conflict between the different tasks is hardly manageable for the team, but especially for the individual, and is a great source of stress. A possible way to solve this conflict – both in the interest of the flow of work and in the interest of the people – is the combination of Kamishibai and Kanban.

Kanban for project and support work

Let’s first consider Kanban as a way to manage project and support work – planned activities and spontaneous requirements together: Unlike Scrum1, which is oriented on a concrete product and structured in sprints – which is often Maslow’s hammer of agility – Kanban enables any kind of work to be organised in a continuous flow.

In a Kanban system, it is easy to mix planned and spontaneously reactive items and manage them in a common work system2. However, Kanban does not only consist of a blackboard and cards – and this is often done out of sheer enthusiasm for the supposedly simple “agilisation”: The deliberate limitation of simultaneous work (“WIP limit”)3 and the establishment of a possibly largely self-organised pull system are also fixed and extremely effective elements of Kanban, in addition to the visualisation of work. They do not only serve the (flow) efficiency, but also make Kanban a very human method – not although, but because the focus is on managing the work and not the people! An optimisation of the workflow is not necessarily in conflict with the needs and wishes of the people – and the consideration of the latter is, by the way, a yardstick that seems to me to be applied far too rarely, especially to new methods.

Kamishibai for repetitive tasks

The conflict between planned project work and reactive-spontaneous activities can therefore at least be alleviated, if not solved, through joint management of these types of work in a Kanban system. But how to deal with the third type of work, with maintenance, with recurring activities of all kinds? Kamishibai4, a remarkably little-known tool from the world of lean production, can help here – and can also be combined wonderfully with Kanban.

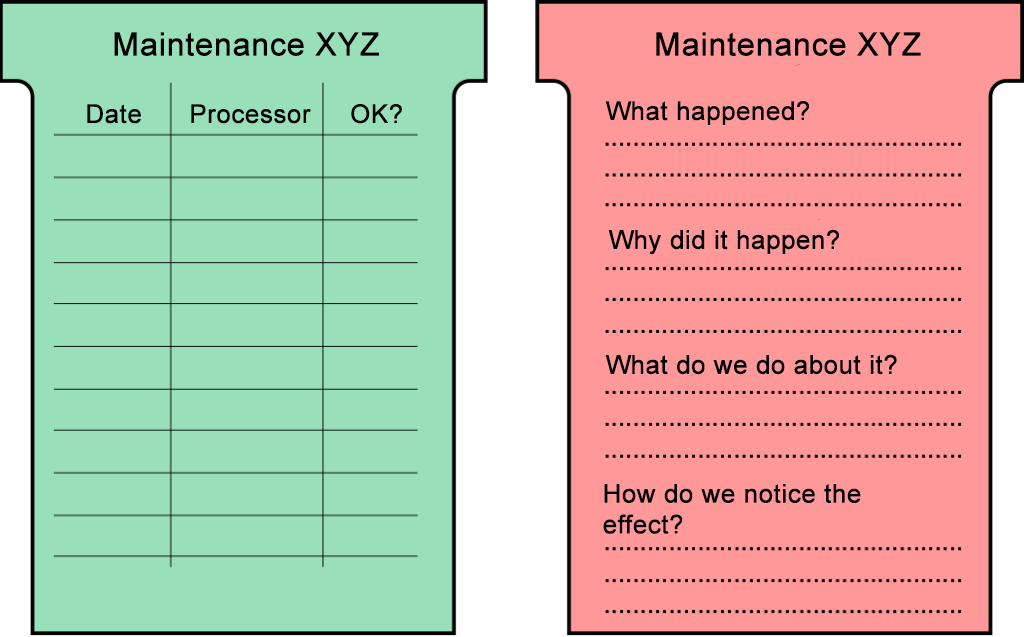

Originally Kamishibai refers to a kind of “paper theatre”, in which the narrator visually underlines his story by means of pictures pushed one after the other into a stage-like frame – now widespread and popular in Germany in the field of elementary education. In the “lean” world, Kamishibai also describes a stage in a way: On the Kamishibai board – often realised as a T-card board with two-coloured red-green cards – one can see the status of maintenance tasks and in the context of a Gemba-Walk (or more formalised audits) the board tells stories in a way by means of the colour status of the cards and the notes on them.

Unlike a Kanban board, the columns of a Kamishibai board do not represent the steps of the work, but the cadences or repetition frequencies in which regular activities are to be carried out – there is, for example, one column for daily, one for weekly and one for monthly activities:

Depending on the “completed” status of the regular task, the cards on Kamishibai can have their red or green side facing forward – the (usually astonishingly large) total amount of recurring activities and their status can thus be visualised at a glance.

The two sides of the cards can also be used for notes: The green side, for example, can be used to log activities, the red side to document problems and errors (and any agreed countermeasures) that have occurred during the work. The Kamishibai cards and the board can thus become a real kaizen tool – and where could continuous improvement be more worthwhile than in repetitive (maintenance) activities?

Kamishibai and Kanban

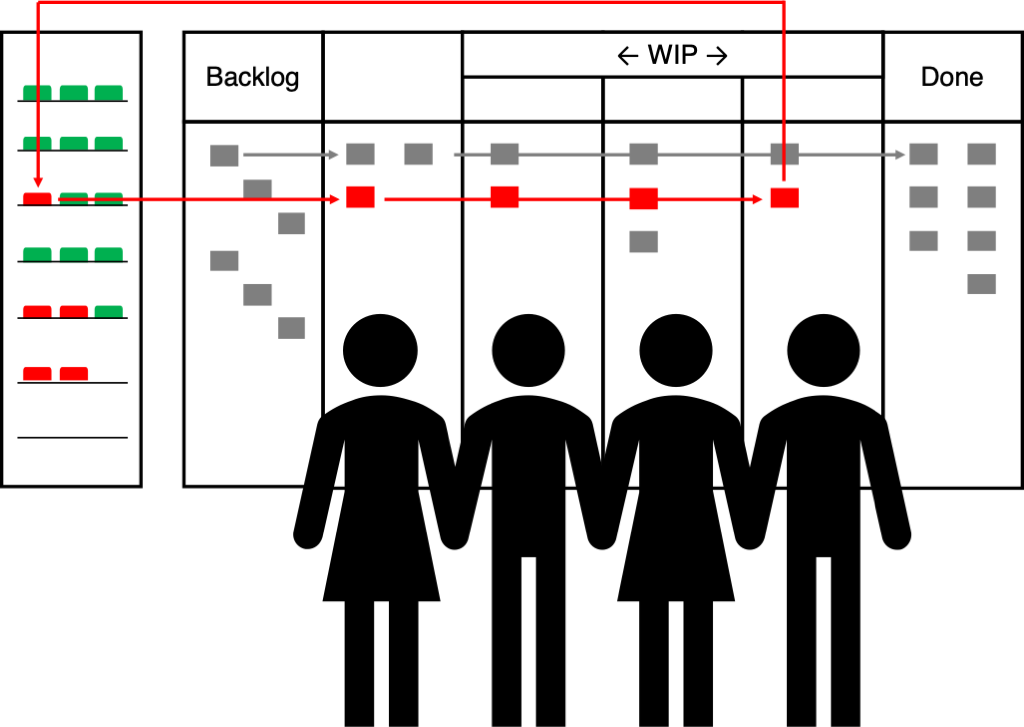

In itself, Kamishibai mainly provides an overview of routine activities and their status and serves as a tool for quality improvement. Even greater impact can be achieved by combining Kanban and Kamishibai5.

Ultimately, a card on the Kamishibai board, just like a Kanban ticket, only represents work. It is therefore obvious to treat both kinds of work in the same way as far as possible: If a routine activity is due at the Kamishibai board, the card moves to the Kanban board and there through the normal flow of work with all its rules and agreements – especially with its WIP limits. When the work represented by the Kamishibai card is done, the card does not move to the (however named) column “Done”, but back to the Kamishibai board.

- planned (project) tasks,

- spontaneous reactive (support) activities and

- regular (maintenance) activities

can be managed in one work system – the competing demands become more manageable for the team and the individual and improvements in the workflow automatically affect all three types of work.

Kamishibai not only fulfils the Kanban practice “Visualise [all work]”, but also fits seamlessly into the Kanban cadences:

- In the “Kanban Meeting” or “Daily [Standup]” the Kamishibai is checked for due tasks, what needs to be done is moved from the Kamishibai board to the Kanban board and what is done is moved back from the Kanban to the Kamishibai board.

- During the “Service Delivery Review”, problems that have occurred are discussed and improvements are verified – often based on the information noted on the Kamishibai boards (see above).

- New (routine) tasks – new Kamishibai cards – are added to the Kamishibai during the “Replenishment Meeting”. Many maintenance tasks are the result of continuous improvement – so the suggestion for this often comes from the above mentioned “Service Delivery Review”.

Routine work is routine – and therefore often virtually in the blind spot of the respective work system. What is in the blind spot is often overlooked – in this case at the expense of quality, but also at the expense of the people who have to do this hidden work “on the side”. A Kamishibai can create transparency here, make hidden work visible and bring it back into the “normal” work system – in the interest of quality, but above all also in the interest of the people.

Notes (in German):

[1] Zur Eignung bzw. Nicht-Eignung von Scrum für gemischte Arbeit vgl. bspw. https://die-computermaler.de/warum-mir-scrum-im-it-infrastruktur-bereich-oft-als-wenig-sinnvoll-erscheint/ (01.11.2020).

[2] Beispielhaft für die Anforderungen einer mittelständischen IT-Abteilung genauer ausgeführt unter https://die-computermaler.de/proto-kanban-fuer-admins/ (01.11.2020).

[3] Zur Wirkung von WIP-Limits vgl. bspw. https://www.kanbwana.de/2019/10/01/podcast-warum-wir-wip-limits-verwenden/ (01.11.2020) und https://die-computermaler.de/littles-law-wie-man-wip-limits-moeglichst-nicht-erklaert-und-wie-es-vielleicht-besser-geht/ (01.11.2020).

[4] Vgl. bspw. (aus dem “Lean”-Umfeld) https://blog.gembaacademy.com/2006/11/21/what_is_a_kamishibai/ (01.11.2020) und (eher aus dem IT-Umfeld) und https://die-computermaler.de/kamishibai-in-der-it/ (01.11.2020).

[5] Mehr zur Kombination von Kamishibai und Kanban unter https://die-computermaler.de/kamishibai-und-kanban/ (01.11.2020).

Tim Themann

For more than a decade, Tim Themann has headed the consulting department of a medium-sized system house in Hamburg and advises customers on technical and organisational issues of IT infrastructure and IT operations. In numerous consulting and implementation projects as well as workshops and trainings he leaves a broad trail of whiteboards and flipcharts covered with visualisations. In his spare time he writes about project management and visualisation topics in his blog.