‘Our group dynamics are…’ – yet another misunderstanding

The request usually comes from the human resources development department: ‘We have a team here and the manager wants team development.’

Why?

‘Well, the colleagues should get closer together, exchange ideas in a relaxed atmosphere and develop a stronger sense of unity. There are always group dynamics, i.e. sensitivities among the members.’

So far, so normal and, unfortunately, illogical. Because the ‘problems’ described in this way are usually not well observed, but rather hastily diagnosed.

In everyday language, it seems to me that group or team dynamics are increasingly equated with ‘we have emotions’. And emotions, as many organisations agree, have no place at work. This is a first error in thinking that needs to be examined more closely. To understand this, it is worth taking a brief look at what is meant by group dynamics in systems theory. Namely, the independent life, the interplay of forces within a team. Assuming that every group is more than the sum of its parts (i.e. its members), the observation of what is going on is not broken down into individual parts, but examined in terms of their interactions.

Cooperation without emotion is like beer that has lost its carbonation: dead.

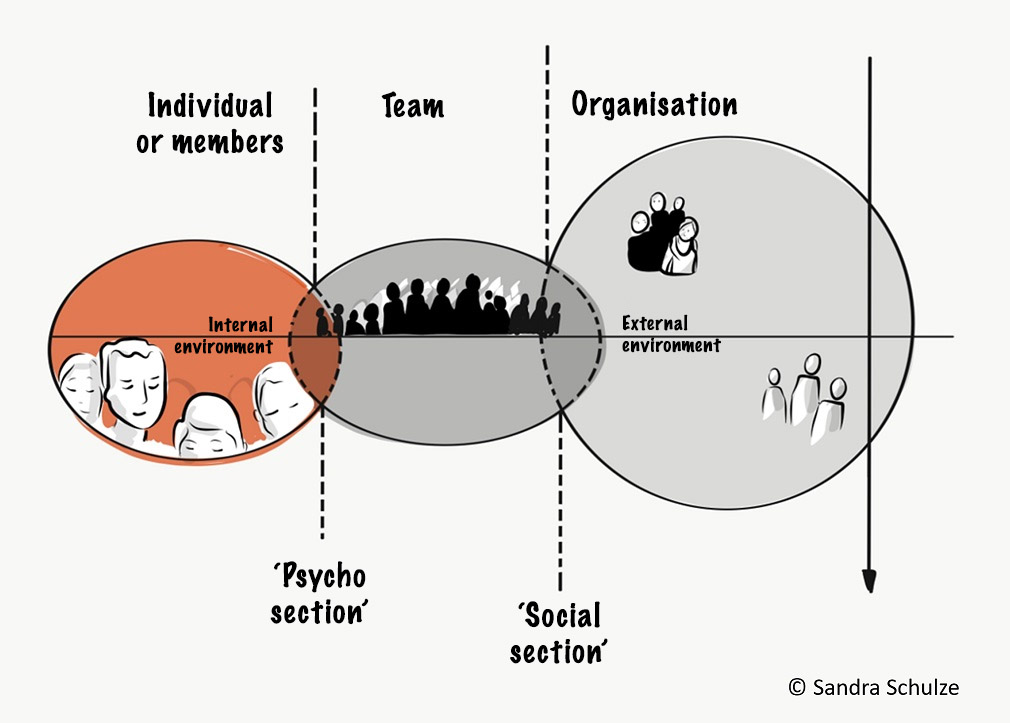

However, this is not a plea for emotional fireworks at all times, but rather a call for attention to necessary adaptation processes. Every team has environments from which it distinguishes itself and which, at the same time, have an effect on it. It is not the sum of the team members that makes it what it is. It makes sense to distinguish between the external and internal environments. [1]

Figure: Group dynamics – interaction between the external and internal environment

- What is the team’s task?

- What are the guidelines regarding working hours or clothing?

- What goal should the team achieve?

- Who belongs to the team and who receives what salary?

All these aspects determine the internal order. Of course, the organisation does not completely determine what a team does. The team decides how to deal with the guidelines and which ones to follow or ignore. The team develops through the demands of this external environment; it is not determined by it.

The second boundary is between the team and its internal environment. No team can accommodate all the needs, values, opinions or behaviours of its members. It would descend into chaos. This limitation provides orientation, especially for the members.

We are individuals, but only within limits, because as members of a group or team, we are also its product. We cannot fully express our personalities. There is not enough space for that, and it could end up being about nothing else but the various sensitivities and corresponding tensions.

Therapy group or committee?

Every team develops by setting boundaries with its environment. If you look closely at these interfaces, you can see what is most important to the team in question. If thinking and talking increasingly revolves around the internal environment, then it easily tips towards a self-help group, where members like to philosophise a lot about themselves and their feelings. Basically, this is precisely the boundary that makes a team independent. It takes shape. At the same time, this is a good point to ask yourself (as a team) about the meaningfulness in terms of the organisation and value creation. Joint reflection can help here.

Structural conflicts arise primarily at the interface with the external environment. What task does the team have to perform and what resources can it use? What paradoxical demands does the organisation make? Old versus new, economical versus standardised, proven versus innovative, and so on. This constant conflictual process shapes the team. How does this affect the ‘inner workings’ of the team?

Of course, each individual is in a constant process of adapting to the team. This is an area of tension that can provoke just as many conflicts as at the team level.

Group dynamics are not one-dimensional

In a larger company, I have repeatedly accompanied teams that are strongly focused on the external environment. The frequent argument: ‘We are just the leftovers here. We have no common tasks.’ As a result, employees consider ‘team days’ to be completely superfluous, while managers miss cooperation and involvement.

Looking at the individual, the team and the organisation can fuel the discourse and possibly increase insight and commitment. Even if the organisation has strange guidelines and expectations, the manager does not take a clear stance and there is little overlap in tasks, it is still up to the individual to look for commonalities and shared boundaries. This is an ongoing process that is never complete. And thus, whether we like it or not, it is an imposition on everyone involved.

A final thought

Group dynamics are not a disruptive factor, but rather the natural expression of lively collaboration. They show how teams react to internal and external influences. Sometimes frictionally, often productively, always significantly. Those who understand dynamics instead of rushing to judge them can use them in a targeted manner to promote orientation and development.

Team development is not a cosy event, but a reflexive balancing act between adaptation and differentiation. Every manager and HR development department should clarify in advance whether this is the appropriate intervention. In organisations where each team receives an annual budget for ‘socialising’, I recommend simply going to an Italian restaurant or bowling.

Notes:

[1] It is worth taking a look at Einfuehrung in die Gruppendynamik (Introduction to Group Dynamics) by Oliver König and Karl Schattenhofer, published by Carl-Auer Verlag in 2016.

Stephanie Borgert wants to make a difference to the people she works with. You can easily get in touch with her on LinkedIn and discuss group dynamics and managing complexity. Alternatively, it is also worth taking a look at the interesting books she has published.

Would you like to discuss group dynamics as a multiplier? Then share this post in your network.

Stephanie Borgert has published more observations on the t2informatik Blog:

Stephanie Borgert

Stephanie Borgert is a complexity researcher and engineering computer scientist. Managing complexity and dynamic, complex projects are her passions. This is because they include essential aspects such as leadership, management, communication, mindfulness and systemic thinking.

Together with her customers, she repeatedly finds that it is often not the large, styled and strict processes, but rather the many small adjusting screws in a system that make it more goal-oriented, appreciative and successful.

Stephanie Borgert, a former business columnist for the Frankfurter Rundschau, has now published eight books. Her book ‘Unkompliziert!’ was a business bestseller in 2018.

In the t2informatik Blog, we publish articles for people in organisations. For these people, we develop and modernise software. Pragmatic. ✔️ Personal. ✔️ Professional. ✔️ Click here to find out more.