Constructivism in organisations

Actually, it’s just a picture that I show and one or two questions that I ask about it in many of my workshops:

- What do you see in this picture (above)?

- And what would your mother call it?

On the one hand, it amuses participants. It also often gives me a regional classification of where the participants live or where they come from. On the other hand, it makes constructivism so wonderfully visual. ConstructiWhat?

Communication is and remains one of the greatest challenges facing humanity. It causes the greatest conflicts and increases the challenges for many things and issues. Unfortunately to a lesser degree for understanding or affection.

Dealing with this has become even more difficult in recent years and who doesn’t sit in front of social, interactive media from time to time and shake their head at what is said and what happens there.

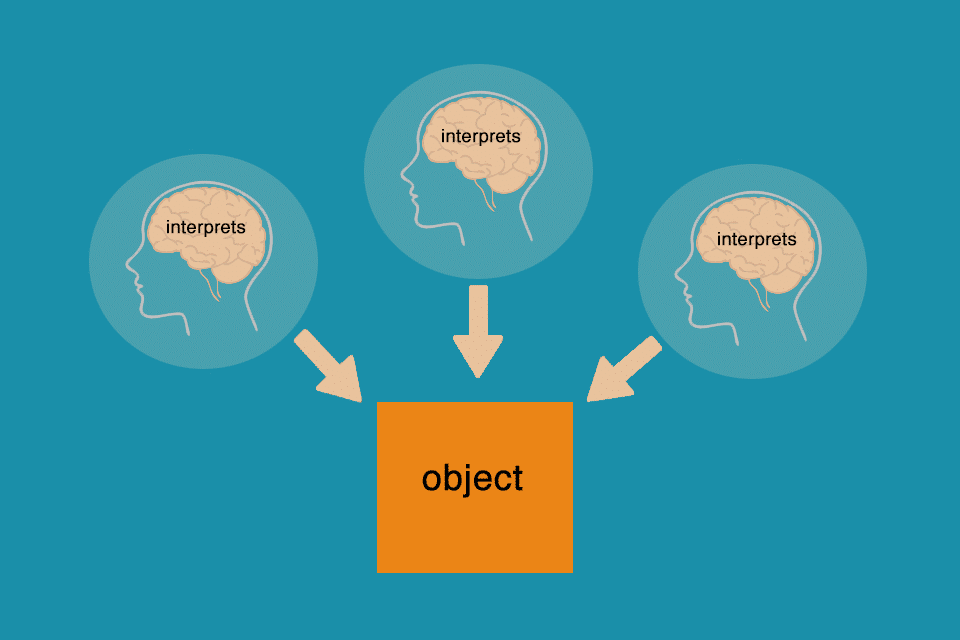

Head is exactly the right keyword and the connection to constructivism. The basic thesis of constructivism is that reality for each individual is always a construction of his or her own sensory stimuli and memory.

Objectivity and reality

Objectivity is an impossibility. And there is neither an absolute reality nor a truth. There is only a first-order reality: physical and largely objective object properties. Everything else is a second-order reality and is primarily based on communication.

Put a little more tangibly: We all have more or less distinct senses such as eyes, ears, etc. and a processing organ, the brain. This is shaped by our genetic make-up, our socialisation and our experiences. What we take in is processed there. That’s why we sometimes call a roll a “Brötchen”, sometimes a “Weck”, sometimes a “Semmel”, a “Rundstück”, a “Kipfl”, a “Laabla”. Most of the time we agree on a regional name.

Reality and communication

Reality only comes into being through communication. And thus also through the vocabulary used.

The crutch that people use in most cases is speaking in images, metaphors and stories. It helps us to make ourselves understood. As images converge in the minds of globalised humanity, we should find it easier to communicate with each other. At the same time, however, images again set a trap that we like to walk into: Images can be interpreted in different ways. (The winners write the story). Seeing a scene or an object from different angles and thus interpreting it differently was brought home at the latest by the parable of the blind men and the elephant. (The parable is attributed to Buddhism, among others. Six blind monks examine an elephant and discover a tree, a rope, a snake, a wall,…) It happens every day, billions of times.

Two beautiful examples of constructivism

There is a scene in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy in which a sperm whale and a petunia pot “come into being”. The sperm whale crashes to earth and gives names to the things around it and comments on them. The scene is abstruse in several respects, but also describes beautifully how the world around us is constructed only by us in thoughts and words.

The second example is the so-called Bielefeld Conspiracy.

Niklas Luhmann one of or the greatest sociologists and researched and taught at Bielefeld University. From him comes the statement from the early 1980s: “What is not talked about in the (mass) media does not exist”. Presumably the causal trigger of the Bielefeld conspiracy (“Bielefeld? That doesn’t exist”), which in turn was used by Bielefeld Marketing GmbH to bring Bielefeld into the media and thus into consciousness:

Consequences for companies

So what are the consequences of all this for our (or my) dealings with the world out there and the topic of “cooperation in organisations”?

Every person perceives himself and his environment differently and interprets it for himself. Every person has different abilities to communicate. I.e. each person (out there in the world) develops their own truth, there is virtually no common truth. Especially in 2020, it is once again evident that even objectifying experiments from science are often not recognised and people construct their own truth (The good Galileo Galilei has already had similar experiences “And yet the earth turns!”). To be fair, scientists also construct “their” world. Mostly, however, they enter into a discourse, find a common language that people from another field first have to learn to understand.

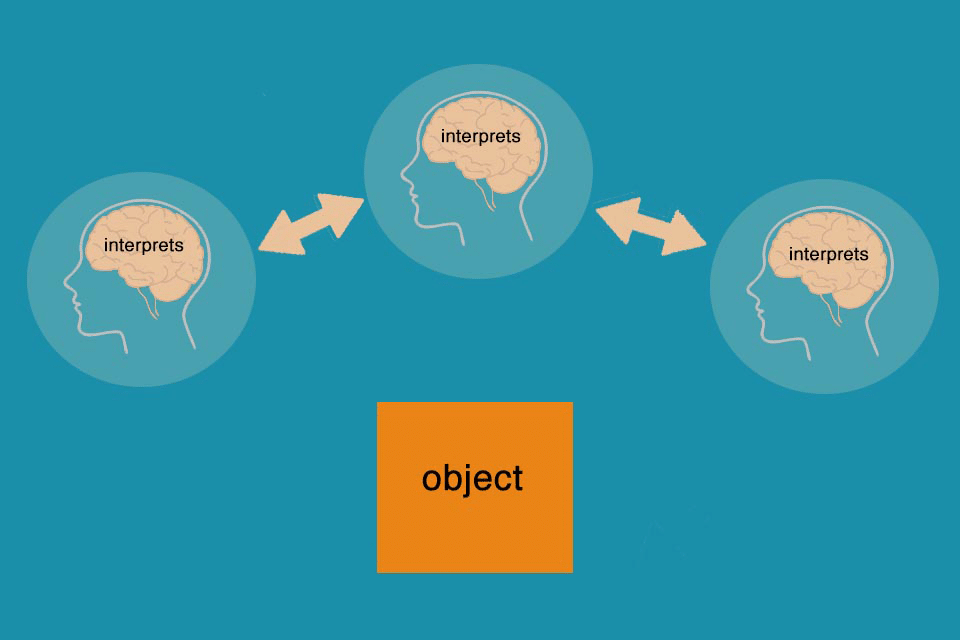

This is first of all to be accepted (with the exception of the intention to lie). Own and common experiences of the peer group play an essential role in this. Objectively, each person can then only accept from the other person to have the same or a different perception (and interpretation).

Directly reading or influencing other people’s thoughts is (fortunately) science fiction. At the same time, however, the awareness that each person only constructs his or her reality can be very relaxing for the soul. So if someone in your environment is convinced that the Covid19 Lockdown exists/existed only to change the batteries in the surveillance doves, so what? He/she has constructed his/her truth that way and surely has good reasons for it.

At the latest, however, when he/she calls changing the batteries “truth”, one could try to explain the concept of constructivism using a bread roll. Or a Semmel or a Weck…

Dealing with constructivism in organisations

But how can a conscious handling of “real existing” constructivism in organisations succeed?

At the latest in training or studies, we have all noticed how similar types of people are found in training or study programmes and how the language differs from neighbouring training programmes. This runs through professional groups and departments (or cohorts). Doctors and nurses, HR departments and purchasers, project managers and sales, IT and technical departments, marketing and controlling. The list goes on and on.

Unfortunately, this does rather less to help an organisation move forward. So what to do?

At the very least, we should focus on the things that help us humans overcome the constructivist communication gap:

- The formation of small groups and

- the identification of common interests.

The classic thing is to form small groups. We tend to be better able to engage in useful communication when we are in smaller groups. This is encouraged because belonging is one of our basic needs. Belonging to manageable groups. These can consist of 3, 6, 12, 50, 150 or more people. Why these values? Because we typically begin to form sub-groups at these boundaries, which in turn need a reason for their cohesion.

The second essential factor is common interests. The professional group of purchasers or payroll accountants, for example, form these through their professionalism. In the case of mixed professional teams, an external impulse is needed. Something as banal as common goals. The clearer and simpler the common goal, the more successful the joint work. But even to agree on this, the constructivist communication gap must be overcome. Jointly developed strategic goals, a vision, a purpose, a mission, MOALS,… could be appropriate tools. (In 2021, we have more or less agreed on such vocabulary to give meaning to our actions).

Conversely: one should be aware that goals are nothing more than a communication tool! Do I want to bake bread rolls, Semmels, Wecks? Or bread? Or cake? Or liver cheese? Even these banal examples show the need for an agreement process…

Models, approaches and vocabulary for constructivism

It is also helpful to use the same models, approaches and vocabulary. A question I am asked again and again: Which is better: Prince2, PMI or IPMA? In most cases it is the same. The crucial point is to agree on a common framework. Internally, with customers and with suppliers. The same applies to agile concepts, leadership models, organisational forms, etc.

The key is to create a common language space and similar thinking. For example, through joint trainings, using the same models or certifications/educations. This is the crucial step to be able to communicate. Just like the concept of constructivism. If my peer group and I know the concept, we have expanded our vocabulary.

Now you might think that we humans only had to agree on a set of vocabulary once after all. Unfortunately, another human phenomenon comes into play here: we don’t just like belonging, we like delimitation just as much. At some point, groups become too big and we want to separate ourselves with a subgroup or another group. Without this desire, fashionable and regional phenomena would be inconceivable. Whether in (recurring) clothing styles, first names for children, designations for small loaves of bread or management approaches. Belonging and demarcation, an eternal recurrence.

It’s good that the concept of constructivism exists. It helps to take a step back, to observe one’s own actions and those of the environment, and that relaxes me immensely! You too?

Notes:

Would you like to discuss the topic of “Constructivism & Organisations” with Carsten Frank or work together with him as a consultant at Campana & Schott? Just get in contact at LinkedIn.

Carsten Frank

Carsten Frank is a Consultant & Expert Manager at Campana & Schott Hamburg. His personal mission is to help medium-sized companies become a little more future-proof and to support organisations in the public sector to use taxpayers’ money a little better. His current focus, in addition to building and developing temporary and permanent project organisations, is also particularly on the topics of strategy implementation and transformations of all kinds.

Prior to 2018, Carsten Frank was, among other things, responsible for multi-project management as head of project management in various organisations for 10 years. He is a qualified industrial mechanic, business graduate, project director (IPMA Level A) and systemic organisational developer. He owes his first contact with constructivism in the 1990s to Prof. Christian Scholz.