Change projects work! – Part 2

The Practice of Change Projects 4.0

Many change projects relate to a linear, predictable and therefore controllable environment. Plannable processes are propagated, standardisations, methods and certifications are sold. However, this has nothing to do with reality. On the contrary: This is – as described in part 1 of the article – planned economy project theatre!

Today the environment of companies is becoming increasingly uncertain, complex and dynamic. In discussions this is often titled with the acronyms 4.0, VUCA or Disruption. This new environment leads to the fact that organisations need Change Projects 4.0, which extend the classical repertoire 2.0 of the last twenty years. This article is about this extension and the practice of Change Projects 4.0. In particular, I describe project parliaments and consensus workshops, as well as decision making through consent and consultation.

Change Management 2.0 vs. Change Management 4.0

Classical 2.0 approaches had sufficient time for communication, using resistance and learning the changed rules of the game. Today, less time is available for a Change Project 4.0 – with greater uncertainty. I call this development “change on the fly”.

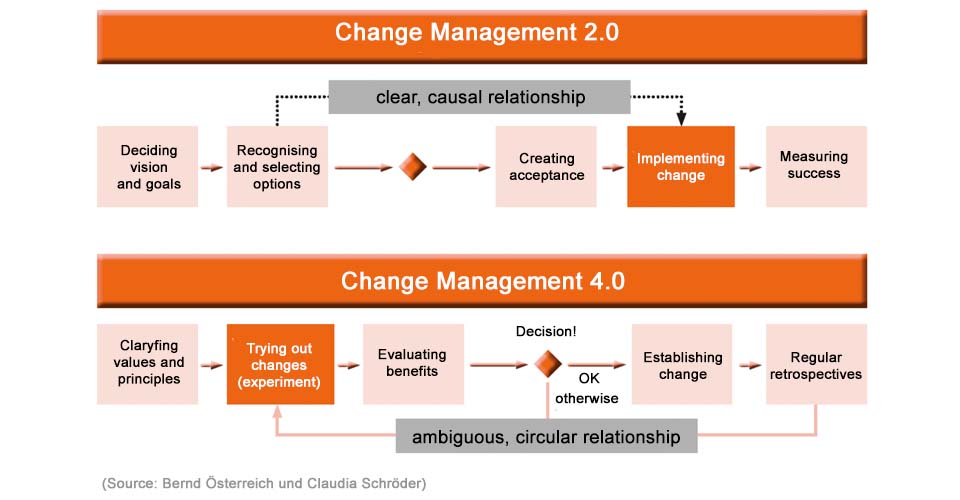

The following figure makes it clear that classical Change Management 2.0 follows a linear and causal model, whereas newer approaches are circular and experimental. First of all, the values and principles of transformation are clarified, before entering a phase of experimentation. The results of these experiments are evaluated from the point of view of benefits and either established or discarded before a new phase of experimentation begins.

The difference between organisational projects 2.0 and 4.0 lies in the deliberate ambiguity of the approach and the deliberate experimentation! Thus, “Change on the fly” returns to the purpose that projects were actually supposed to fulfil: pioneering work!

In the DIN 69901 standard, a project is defined as follows: “A project is a venture that is essentially characterised by the uniqueness of the conditions in its entirety, such as objectives, temporal, financial, personnel or other conditions, demarcation from other projects and project-specific organisation”.

The authors of the standard emphasised the “uniqueness”: Projects and especially organisational projects are about doing something that has not been done before and probably will not be done again so often. And for this purpose, a project-specific form of organisation is used. The standard, on the other hand, does not speak of setting up and executing a plan or even roles, processes or methods that are to be applied in a standardised way for all types and objectives of projects.

Project parliament and consensus workshop

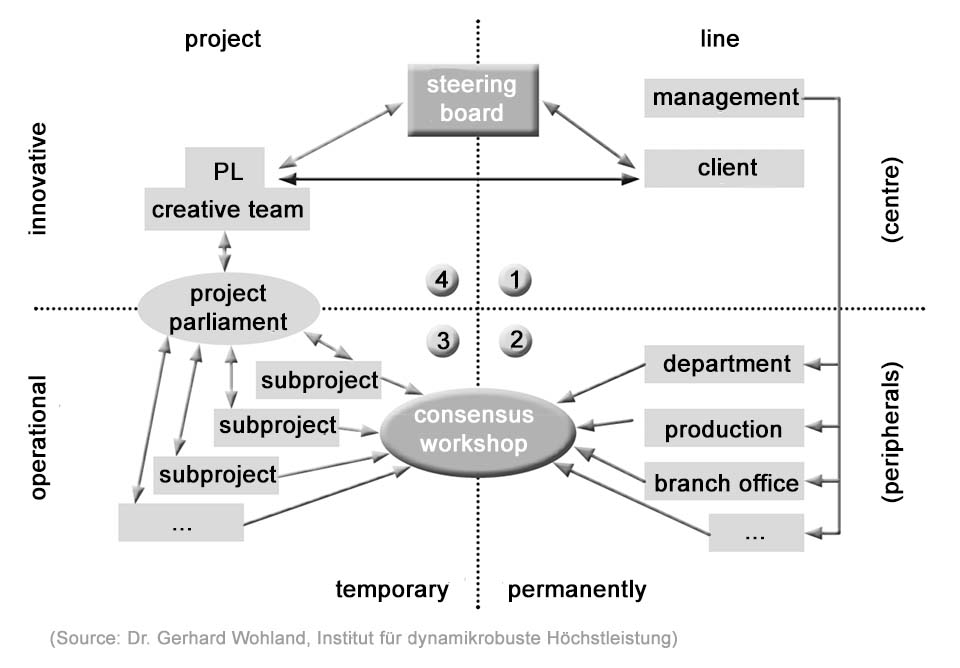

A good example of how the repertoire is being expanded from 2.0 to 4.0 is the project parliament and consensus workshop of Gerhard Wohland.

However, when things become complex, the intelligence of the group is needed, which can be activated, for example, by the 4.0 large group formats project parliament and consensus workshop.

In the project parliament, the project management (or the core or “creative” team) and all sub-project staff and all stakeholders negotiate interests, goals and non-goals. The project parliament meets as needed, at least whenever a change request is made or the project backlog is subject to major adjustments. According to a previously agreed decision-making rule, the project direction and implementation are jointly negotiated and decided here.

The project parliament differs from the familiar meetings, sessions, stand-ups or reviews primarily in the following ways:

- the setting as a negotiation, i.e. communication is based on interests and not primarily on results. The responsibility for creating the project object remains with the subprojects at all times.

- the constant alternation of work on decisions in the overall group (parliament) and negotiation in small groups (committees/ sub-projects).

- the tight moderation (e.g. speech, counter-statement, vote), as is otherwise known from everyday parliamentary life.

The consensus workshop is the body where the operational forces meet and vote on the results of the project work. It always begins with a (secret) vote of all participants on whether the just completed project object will be “accepted”. Therefore, consensus workshops often take place near milestones or in the context of sprint reviews and replace the Powerpoint battle we all know, which otherwise always takes place around the milestone date in the steering board.

It is advisable to make it a condition of consensus workshops that a high approval rate is achieved in the voting process, so that

- on the one hand, to make the decision highly binding and

- on the other hand, to uncover previously uncommunicated conflicts and issues.

A consensus workshop is attended by representatives of the subprojects on the one hand, who present their results, and representatives of the line organisation on the other hand, who are expected to accept the results and take over the day-to-day business. This composition usually creates a certain group dynamic, which must be taken into account in the preparation. It therefore makes sense to have both the parliament and the workshop accompanied by moderators who are experienced in dealing with group dynamics.

Decisions by consent and consultation

Working with groups is also the second example of expanding the repertoire to 4.0: Consent and consultation are effective decision-making processes to support change projects in a meaningful way.

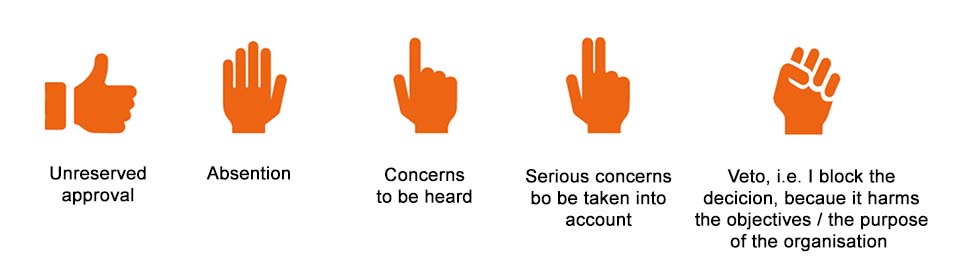

Consent is a format for integrating objections, concerns and fears, which is well suited to “change projects on the fly” and the emotions that often arise in them. Consent is the agreement that no reasoned objection governs the decision-making process.

“Reasoned” means that in consent one not only takes a position but also has to justify why one has taken this position. In the practice of consent building, the hand search, which is shown in the following diagram, has proved to be a good method.

When a decision is made by consent, all those involved jointly try to minimise the objections, i.e. to vary the solution (or to look for completely new solutions) in such a way that fewer or no objections remain.

In a consultation or consultative individual decision, a person decides after having heard a minimum number of participants. This creates clear responsibility for the decision and ensures involvement in the decision-making process. We are familiar with this decision-making format, for example, in the case of doctors, when other specialists are consulted before the attending doctor determines the therapy plan.

A number of principles apply to the consultation:

- The clarification of the problem (the diagnosis) is always at the beginning of the consultation, i.e. the discussion about possible solutions is not helpful at this point and must be consistently avoided.

- When the problem is clearly described, the decision-maker is chosen, because the person leading the consultation must “fit” the problem in terms of expertise, experience and personality.

- It is then up to the decision-maker to shape the process. Who is asked for advice? What is asked? How are the answers documented?

- Once all the advice has been obtained, the decision-maker then makes his own assessment and a decision that is appropriate for the problem and the organisation.

Consultation makes it possible to incorporate the often dispersed knowledge in a speedy procedure and thus arrive at rapid, collective decisions. This requires the honesty of the decision-maker, who is obliged to seek the best and not just the most convenient advice, and the commitment of the advisors, who give their expertise strictly in relation to the problem and as free as possible from tactical and personal motives.

My appeal

I would like to conclude my two contributions with an appeal: Put an end to project theatre and planned economy change projects. Increase the real probability of success of organisational projects. Expand your repertoire. Use project parliaments and consensus workshops. Find decisions by consent and consultation. And if I can support you in your change projects, get in touch with me.

Notes:

Olaf Hinz has published a new book in German: Change Maker – Wirksame Veränderungen unter maximaler Unsicherheit.

In this book, which is well worth reading, he shows how change management must continue to develop in practice. From his more than 20 years of experience as a project manager and change agent, he brings together proven and new aspects of effectiveness.

Olaf Hinz has published additional articles in the t2informatik Blog:

Olaf Hinz

For almost 20 years, Olaf Hinz has been guiding managers, project managers and organisations in transition through troubled waters. He believes that resistance is a powerful signal, change is the rule, and sailing in sight is the appropriate response to the approaching VUCA weather. As a non-fiction author and speaker, the self-confessed Hanseatic citizen and former office manager of Peer Steinbrück is a sought-after source of inspiration at specialist conferences and bar camps.