How do you shape the future?

‘The best way to predict the future is to shape it.’ [1]

Do you remember the medium-sized construction company from No one could have foreseen that? It took a look at possible futures. Regulatory nightmare, digital platforms, circular economy, skilled labour collapse.

These scenarios show what could happen. However, it is impossible to predict what will actually happen.

In When the future appears at christmas, managing director Karl Meier encounters the spirit of the desirable future. Frederike asks him a simple question: ‘What future do you want?’

Karl has no answer. The future just happens.

This is precisely where the real problem begins. As long as the future is understood as something that simply happens, it remains abstract. Only when we ask ourselves whether and how we can influence it does the future become a space for creativity.

The Polak Game: Where do you stand?

Before we look at how the future can be shaped, it is worth taking a quick check-in. It’s about your attitude towards desirable futures.

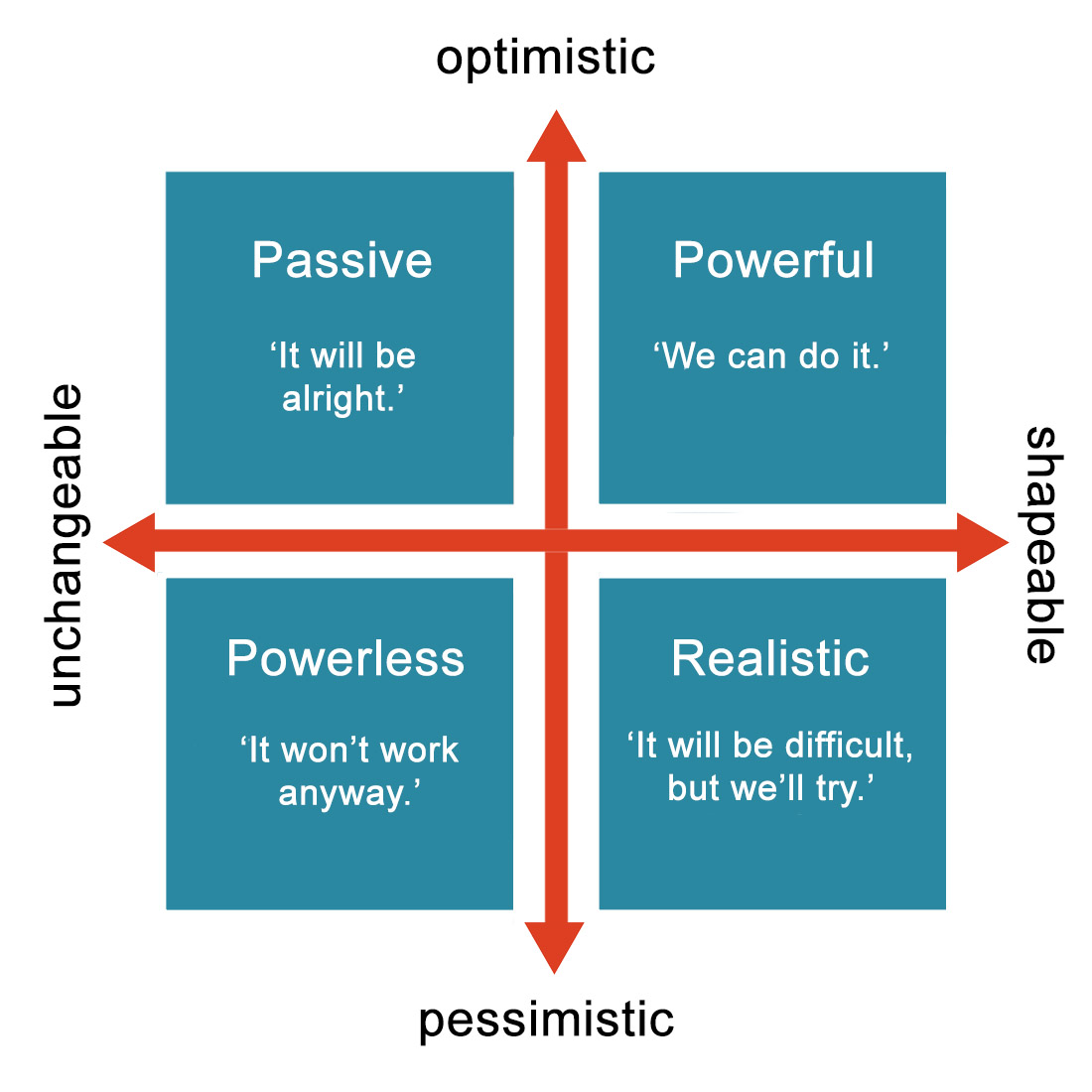

Dutch sociologist Fred Polak [2] developed the Polak Game [3] for this purpose. It helps to classify your own view of the future. It is based on two simple questions.

Question 1: Will the world or your industry get better or worse in the next few years?

(Axis: optimistic versus pessimistic)

Question 2: Can you personally influence the future, or does it just happen?

(Axis: malleable versus immutable)

Take a moment to think about it. Where would you place yourself? Depending on how you answer, you will end up in one of four quadrants.

Figure: Polak Game – Where do you stand?

The Polak Game also works very well as an introduction to a workshop. Let each person take a position, then discuss together: Where does the majority of the team stand? What different attitudes are there?

The future can be shaped

What does science actually say about whether we can influence the future or whether it simply happens?

Sociologist Fred Polak, who developed the Polak Game, explored this question back in the 1960s. In his work ‘The Image of the Future’ [4], he analysed the rise and fall of civilisations over a period of more than 2,500 years. His key finding: societies with strong, positive visions of the future continued to develop. Societies without such visions stagnated or fell apart.

Futurologist Jane McGonigal [5], whom you already know from part 2 of my short series of articles, also provides an impressive example of this. In 2010, she conducted a large-scale simulation at the Institute for the Future [6]. Around 20,000 people played through the course of a future pandemic together.

When COVID-19 became a reality in 2020, participants contacted her. They wrote: ‘I’m not freaking out. I’ve already been through panic and fear when we imagined it years ago.’ After the simulations, people felt prepared, capable of acting and helpful, rather than helpless. In the Polak Game, they would clearly position themselves on the side of those who can shape the future.

Another important contribution comes from economist Saras Sarasvathy [7] of the University of Virginia. She developed the so-called Effectuation Theory [8]. Her core message is that the future is not predictable, but it can be shaped. Successful entrepreneurs do not plan for the perfect future. They start with what they already have (‘bird in hand’). They think in terms of affordable loss rather than expected profits. And they consciously use surprises as opportunities (‘leverage contingencies’). Empirical studies show that these principles are positively correlated with innovation and business success.

What does this look like in practice? The food industry provides an example. The cocoa industry is facing several crises at once. Climate change is reducing yields. Forests are being cleared to make way for new farmland. Pests are destroying entire harvests. The start-up Planet A Foods did not want to simply accept this development. The team developed ChoViva [9], a cocoa-free chocolate alternative based on sunflower seeds and oats from Europe. Fermentation and roasting create a taste that is very similar to classic chocolate.

Here, the future is not waited for, but actively shaped. This is also made possible through partnerships. For example, the Rübezahl-Riegelein Group [10] has switched its entire Sun Rice brand to ChoViva.

These examples show that the future is not created by forecasts, but by decisions. Not every possible future is desirable. But without a picture of what would be desirable, shaping the future remains abstract. The crucial question is therefore not what could happen, but what should happen.

How do you find your desirable future?

In Part 2, you learned about three methods that can be used to visualise possible futures. While reading or thinking along, you may have had the thought at one point or another: That sounds crazy. But it would be good if that were to become reality.

This is exactly where the question of desirable futures begins.

The medium-sized construction company used the 100-things method. One of the possible futures was that trees would be integrated directly into buildings. When this idea was put forward, there was hardly any discussion. Everyone agreed. That would be a desirable future.

Other possible futures, on the other hand, seemed rather daunting. The scenarios included high CO₂ taxes and strict ESG requirements for financing. The company wanted to avoid this development if possible. In this case, the desirable future was not a new ideal, but a clear goal: not to be affected by these taxes.

Desirable futures therefore arise in different ways. Sometimes they are attractive because they are inspiring. Sometimes because you want to prevent a development at all costs.

It is not always immediately clear which future is the right one. And often there is not just one desirable future. In such situations, long discussions are of no help; the only thing that helps is trial and error. Small experiments, pilot projects or prototypes make differences noticeable. They show what works and what doesn’t. In this way, an abstract idea becomes an experiential direction. They dip their toes into the water of desirable futures, so to speak.

Three methods for shaping the future

Now it’s time to get specific. How do you move towards desirable futures? How do you get started with experimentation? The following three methods have proven themselves in practice.

Method 1: Backcasting – thinking backwards from the goal

Traditional planning starts in the present. Where are we today? What can we realistically achieve? How do we get there?

Backcasting reverses this logic [11]. You jump mentally to a target year, for example 2035, and assume that you have already achieved your desired future. From there, you work backwards step by step.

Let’s look again at the medium-sized construction company from parts 1 and 2. The team wants to become the preferred partner for sustainable construction in the region over the next ten years. Planning backwards gives the following picture:

2035 (goal): The company is the first point of contact for circular construction in the region. Sixty percent of projects use reused materials. The team is trained. A stable network of recycling centres and material banks is in place.

2032: Three flagship projects are completed and visible. The local press reports on them. Customers specifically ask for sustainable solutions. Partnerships with material suppliers are established.

2029: The first major circular economy project is underway. Certifications are in place. The team has completed training on demolition and material reuse.

2027: A pilot project with reused concrete is launched. Initial partnerships with regional recycling companies are formed. The team gains practical experience.

2026 (now): What technologies are already available? Who is already doing this today? Initial discussions with potential partners begin. A small test project is defined.

Backcasting makes it clear that the future begins in the present.

Method 2: Design fiction – artefacts from the future

Backcasting is strongly rational. Some teams need something more concrete. This is where design fiction comes in [12].

With this method, you design artefacts from a desirable future. Things that do not yet exist today, but which look as if they came directly from the target year.

Examples

- An instruction manual for a device that does not yet exist.

- Product packaging for a product that does not yet exist.

- An advertising poster on an advertising column of the future.

- A cover of a magazine from the future.

- A TV interview from the future.

When you build an artefact from the future, you have to be specific. The team at the medium-sized construction company has designed a fictional house catalogue from the year 2032. Page 3 shows the Type B circular single-family house. It consists of 85% recycled materials and a digital material passport documents the origin and reusability of each component.

The project manager asks: ‘Who creates this material passport? Will we have software for that?’ Every page of the catalogue raises questions. But that’s exactly the point. Speculation makes desirable futures tangible.

Method 3: Future Present – Telling the success story

The third method harnesses the power of stories. Future Present is a so-called Liberating Structure [13].

The participants collectively transport themselves to the target year. Pioneers and novices sit around a fictional campfire. The pioneers come from the present and have already lived through the transformation. The novices only know the target state and want to understand how it came about. They ask the pioneers simple questions:

- What were the difficult times like?

- What was the deciding factor in tackling the change?

- What were the first steps?

- Who supported and who slowed things down?

- When did it really take off?

The pioneers respond from the perspective of those who have succeeded. This retrospective view changes the way of thinking. Improvisation leads to new insights.

Let’s listen briefly to the people from the construction company gathered around a fictional campfire in 2035.

Novice: ‘What were the difficult times like back then?’

Pioneer: “2027 was exhausting. No one knew exactly how to use recycled concrete. The site managers were sceptical. “We’ve never done that before,” I heard constantly. And the calculations were complicated.‘

Novice: ’What made you decide to continue anyway?‘

Pioneer: ’A call from the city. They wanted a public building constructed using circular economy methods. We didn’t want to lose this project under any circumstances.”

Novice: ‘What were your first steps?’

Pioneer: ‘We started small. With a demolition project on an old industrial building. We documented where the materials came from. That was tedious. Then we built a small extension. It wasn’t perfect, but it worked. The team saw that it was possible.’

From insight to shaping the future

None of the methods presented can predict the future. And none guarantee success. But they change your perspective. Possible futures suddenly no longer seem abstract or unrealistic. You recognise paths. And first steps.

Let’s take a quick look back at this series to conclude.

In The torch into the future, we discussed how there are different types of futures. Probable, plausible and possible. And that the probable future is often the most dangerous. It tempts us to simply carry on as before.

In No one could have forseen that, you learned how possible futures can be visualised. Scenarios help to shift the boundaries of thought and take developments seriously before they become reality.

This third part has shown that the future can not only be imagined, but also shaped. Methods such as backcasting, design fiction and future present help to derive concrete action from desirable images. Not as a grand master plan, but as a sequence of decisions and experiments.

In the end, a simple but uncomfortable question remains: What future do you want to shape? And right behind it, the second question: When will you start?

Because the future doesn’t just happen. It emerges where people begin to consciously shape it.

Notes (partly in German):

Tobias Leisgang is a moderator and coach for companies that want to boldly break new ground. If you’re still finding it difficult to get started, feel free to visit his website or contact him on LinkedIn to take the first few steps together. 😉

On 20 and 21 March 2026, Tobias Leisgang and the Bamberg ambassadors of the Ministry of Curiosity and Future Enthusiasm invite you to the second Camp fuer Neugier und Zukunftslust. In the beautiful Bergschloesschen with its breathtaking view over the World Heritage city of Bamberg, participants can look forward to a weekend that awakens curiosity and ignites enthusiasm for the future.

[1] The quote ‘The best way to predict the future is to shape it’ is often attributed to former German Chancellor Willy Brandt. Other sources attribute it to Abraham Lincoln, who is apparently said to have made the statement much earlier.

[2] Wikipedia: Fred Polak

[3] Peter Hayward und Stuart Candy: The Polak Game, Or: Where Do You Stand?

[4] Fred Polak: The Image of the Future

[5] You found me: Jane McGonigal

[6] Amazon: Jane McGonigal: Imaginable: How to See the Future Coming and Feel Ready for Anything―Even Things That Seem Impossible Today

[7] Wikipedia: Saras Sarasvathy

[8] Wissen kompakt: Wie funktioniert Effectuation?

[9] ChoViva: Was ist ChoViva, wie schmeckt es und was sind die Vorteile?

[10] Quickfacts: Rübezahl-Riegelein-Gruppe

[11] John B. Robinson: Futures under glass: A recipe for people who hate to predict

[12] Julian Bleecker: Design Fiction: A short essay on design, science, fact and fiction

[13] Future~Present: Strategien für eine bessere Zukunft entwickeln

Would you like to discuss the challenges of the future as a multiplier or opinion leader? Then share this post in your networks.

Here you will find an interesting article on the principle of affordable loss.

Tobias Leisgang has published additional posts on the t2informatik Blog, including:

Tobias Leisgang

‘The future is the only place I’ll spend the rest of my life’ – Charles Kettering was right and Tobias Leisgang takes this quote very seriously. After studying electrical engineering, he developed semiconductors, researched the latest technologies with global teams and made the supply chain of an automotive supplier fit for the future.

Today, he helps small and medium-sized companies develop sustainable business models – with a great deal of foresight and a dash of pragmatism. Because there are often many decisions to be made between good ideas and their implementation – and that’s exactly where Tobias comes in: in ‘Kopf & Bauch – Der Podcast der Entscheidungen’, he provides exciting insights into how to make them.

And because standing still is not an option for him, Tobias continues his journey as a future shaper – not in a fancy suit, of course, but as a student in the future design programme. After all, who says you can never learn enough?

In the t2informatik Blog, we publish articles for people in organisations. For these people, we develop and modernise software. Pragmatic. ✔️ Personal. ✔️ Professional. ✔️ Click here to find out more.