Happy birthday, Scrum!

A look at the beginnings, the interim results and the present of Scrum

On 15 October 1995, the Tagesschau news programme began with the announcement that Islamic scholar Annemarie Schimmel had been awarded the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade in Frankfurt. [1] In the USA, the Simpsons episode ‘Lisa the Vegetarian’ aired, featuring Linda and Paul McCartney, in which Lisa decides to become a vegetarian. [2] And me? I had just completed my first two weeks on the job at a telecommunications company and was learning how sales works beyond the business textbooks. Oh yes, and then there was an event in Austin, Texas: the ‘Conference on Object Oriented Programming Systems, Languages, and Applications’, or OOPSLA ’95 for short, where Ken Schwaber presented the SCRUM Development Process. [3] A process that changed the world of software development forever.

That was 30 years ago. Despite the fact that the two Japanese researchers Ikujirō Nonaka [4] and Hirotaka Takeuchi [5] had already mentioned Scrum as a term in a paper in 1986 (according to their observations, small, self-organising teams with self-set goals achieved the best results in the development of complex products), many agilists consider OOPSLA ’95 to be the birth of Scrum.

Happy birthday, Scrum! You are now a proud 30 years old!

The SCRUM Development Process

Ken Schwaber begins with an uncomfortable observation: many companies act as if software development can be planned and controlled in a completely linear fashion. In practice, however, many things change at the same time: technologies mature, requirements shift, and the market and competition provide new impetus. Treating this creative and sometimes opaque process like a precisely calculable machine leads to inaccurate forecasts and frustration. His answer is SCRUM. Not a desire for more control, but the design of a process that takes unpredictability seriously and actively manages it.

The basis of SCRUM is empirical process control. The focus is on frequent inspection, conscious adaptation and visible risk management. Methodologically, SCRUM ties in with iterative and incremental approaches in object-oriented development. The illusion of complete predictability is replaced by a clear rhythm, short cycles and a few robust controls.

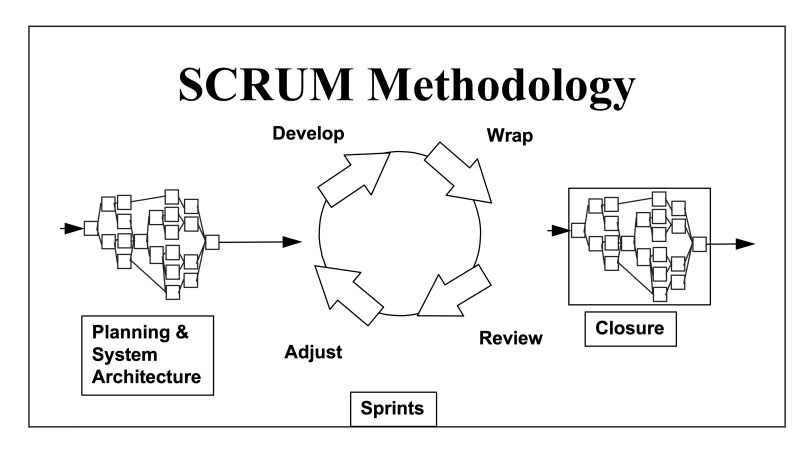

How does this work in practice? SCRUM organises the work into three phases:

Pregame: In the pregame, the backlog and rough release goal are clarified, small teams are named, risks are assessed and the architecture is designed in such a way that changes remain possible. The design is done at a high level and prepares the implementation.

Game: In short sprints of one to four weeks, teams of three to six people deliver executable versions. Each loop follows the same sequence: Develop for implementation, Wrap for integration into an executable version, Review with all relevant participants, Adjust for course and content. The planned release can be adjusted during this time. The adjustment is controlled and based on the observations made.

Postgame: In the postgame, integration, system testing, documentation, training and preparation for delivery complete the work. The product is made ready for release.

Control is exercised using a few clear variables: backlog and planned releases, components to be changed as packets, specific changes, emerging problems, continuously assessed risks, solutions and issues. In each review, these points are made transparent and refined.

In short, SCRUM replaces unreliable predictions with short feedback loops, small focused teams, and visible decisions. This creates reliability in an environment that is constantly changing. At least this summary sounds remarkably similar to the concept we are familiar with today, doesn’t it?

Process, method, approach or framework?

- “In this paper we introduce a development process, SCRUM, that treats major portions of systems development as a controlled black box.”

- “SCRUM is a management, enhancement and maintenance methodology for an existing system or production prototype.”

- “Our new approach to systems development is based on both defined and black box process management. We call the approach the SCRUM methodology…”

These three sentences can be found in Ken Schwaber’s document. SCRUM is described as a development process, positioned as a methodology for managing, enhancing and maintaining systems and prototypes, and declared as an approach. Schwaber obviously uses the terms interchangeably: a process describes a sequence of activities with inputs and outputs. A method is a higher-level scope of action with rules and the how of working. An approach is the pragmatic expression in context, i.e. the concrete organisation and application of the framework for action.

Interestingly, the term framework does not appear in the sense of today’s Scrum Guide. Schwaber only uses framework definitionally in the methodology chapter:

“The approach used to develop a system is known as a method. A method describes the activities involved in defining, building, and implementing a system; a method is a framework. Since a method is a logical process for constructing systems (process), it is known as a metaprocess (a process for modelling processes).”

Had I known this ten years ago, I could have spared myself many discussions about method or framework. Today, when referring to the original, I would consistently speak of process, method and approach. And when discussing today’s Scrum in practice, I would use the term framework and, if necessary, point out the change in terminology and the changed spelling with only one capital letter. [6]

Figure 1: SCRUM Methodology – Excerpt from the 1995 Ken Schwaber Development Process [3]

A journey through time from the SCRUM Development Process to today’s Scrum Guide

Let’s jump to the year 2010. SCRUM has been triumphant for fifteen years now, but companies are mixing practices, consultants are providing checklists, and teams are arguing about terminology. In many places, an empirical framework has become a cocktail of methods. This is precisely where Ken Schwaber and Jeff Sutherland kick in: the Scrum Guide is intended to create a common minimum. A lean framework, clear language, few rules, lots of freedom. Not a recipe book, but a reference.

The first edition in 2010 sets the guidelines. [7] Scrum (now only capitalised in headings) is described as a framework for the development of complex products and systems based on empirical process control. Transparency, inspection and adaptation form the foundation. The cycle is the sprint. The end result is a potentially deliverable increment. Roles and events are named, timeboxes are clearly defined, and the tone is pragmatic. The goal is a common vocabulary that provides guidance without shackling teams. [8]

Shortly thereafter, a new risk emerges. Where rules provide guidance, they threaten to degenerate into checklists. The 2011 versions deliberately streamline. Teams no longer make sacred vows about scope, but deliver a forecast. Burn-downs and release plans may help, but are not mandatory. The product backlog is organised rather than rigidly prioritised. The guide makes a clearer distinction between rules and helpful practices. Think instead of following a recipe. [9] [10]

In 2013, the focus shifts to the point where many decisions fail: lack of transparency. A separate section makes it clear that poor insights arise from poor artefacts. Sprint planning is described as an event with two topics, and the sprint goal is explicitly reinforced. Grooming becomes refinement. The daily is sharpened as a planning event, and timeboxes are clarified linguistically. The framework remains lean, and the inspection points become more robust. [11]

2016 adds what makes empiricism viable. The five values of commitment, courage, focus, openness and respect are anchored. They address behaviour, not technology. The message is: without lived values, transparency remains a façade and adaptation a coincidence. The guide thus names the social statics behind the method. [12]

2017 sees fine-tuning based on practical experience. Scrum is classified beyond software. The daily is formulated even more clearly as a planning event. At least one prioritised improvement from the retrospective is moved to the sprint backlog. The increment is specified as inspectable done work. It is about contour, not expansion. [13]

2020 significantly streamlines the text and eliminates a common organisational pattern. Instead of a development team in the Scrum team, there is a team with three responsibilities. Product owners, Scrum masters and developers work towards a common goal. New is the product goal as a long-term point of reference. Each artefact receives a commitment: product goal in the product backlog, sprint goal in the sprint backlog, definition of done in the increment. The language becomes simpler, the product focus clearer. [14] [15]

This creates a consistent line over the years. First a common core, then the correction against formulaic thinking, then transparency, values and fine-tuning, and finally a very lean reference text with clear responsibilities and commitments. Anyone talking today about daily, definition of done, increment or product goal can locate here which problem these elements solve and when they found their place in the guide. [16]

The present state of Scrum

How do you feel about Scrum today? More meetings than impact? Effective collaboration, but few results? Or do you experience short cycles, clear decisions and regular learning?

The present state of Scrum often seems ambivalent. There are many reports circulating online about a lack of success. At the same time, extensions such as the Scrum Expansion Pack are emerging, which are intended to provide more depth and context, or frameworks for scaling to make the elements suitable for large corporations. So does Scrum have a problem? Are organisations struggling with misunderstood or half-hearted agility? Or are practical challenges beyond the scope of Scrum?

Different perspectives help to answer this question. The first focuses on the why. Scrum is designed for situations with high dynamics and uncertainty. Those who expect efficiency above all else are starting with false hopes. In complex situations, impact comes first, then speed. Effectiveness beats efficiency because a perfectly optimised process will fail elegantly if the product is wrong. That is precisely the promise of agility: finding out faster what really works and focusing on that.

This is followed by empiricism. Scrum only works if teams plan, measure and learn visibly. Measurement is feedback for the team, not remote control for the hierarchy. If velocity is managed upwards, metric theatre ensues: points rise, insight declines, motivation crumbles. It is better to interpret key figures where context is available and use them as a starting point for decisions and improvements.

The third lever is customer proximity. Sprint reviews without real users are common. Then product development remains a guessing game. The review serves to check the increment and adjust the backlog. Without the most important stakeholders, there is no market feedback to sharpen priorities and accelerate learning.

Discipline is also needed on a small scale. Many retrospectives produce long wish lists, but little implementation. The retro becomes effective when concrete improvements are incorporated into the next sprint and become visible in the sprint backlog. Every measure requires root cause analysis and accountability, an expected outcome, and a criterion for recognising success.

Another area of tension is scaling. As the product and organisation grow, dependencies accumulate. The frequent response: additional committees and status presentations. It is more effective to actively reduce such dependencies, bring real decision-makers into the learning cycle, and choose formats that enable quick help rather than staging control. [17]

Ultimately, context is what matters. Scrum is not a panacea. In stable, predictable markets, a lean, predictable process often provides more benefits. Many organisations need both: exploratory in some areas, efficient in others. This requires regular discussions about market logic, risks and the real need for agility, rather than introducing agility as an end in itself.

These typical disappointments rarely indicate a flaw in the framework. They point to a lack of purpose, incorrectly applied metrics, insufficient customer feedback, too many dependencies and too little focus on improvement. If the foundation is right, Scrum proves to be a lightweight operating system for learning under uncertainty: short cycles, clear decisions, visible results. Extensions then have their place, but not as a substitute for what must be in place first.

Long may you live, Scrum!

Scrum has rewired work. Not as a trend, but as a tactic for the essentials: impact before speed, learning before linearisation, product before project. An idea became a triumphant march through development departments, product teams and entire organisations. Because short cycles, clear goals and visible increments deliver results. Period.

Scrum wins where other methods fail: in uncertainty, in changing assumptions, in genuine complexity. Transparency, inspection and adaptation are not posters. They are the engine. The sprint fixes the time. The goal determines the scope. The increment makes progress negotiable. This makes movement measurable and decisions better.

The strength of the framework lies in its conciseness. Few pages, enormous impact. Anyone familiar with the development of the guides can read between the lines to see the intention: not a recipe book, but a minimum of rules that enforce focus and make responsibility visible. Product goal, sprint goal, definition of done. Three commitments, one compass.

And yes, Scrum demands attitude. Courage, plain language, consistency. Roles that make decisions. Key figures that belong to the team. Reviews with real users. Retrospectives with tangible measures. Those who deliver this will see results. Those who play theatre instead will get theatre results. It is not the framework that fails. It is the application that does so from time to time.

So: Happy Birthday, Scrum! 30 years and not a bit tired. Long may you live, you impressive framework. Thank you for turning uncertainty into progress and complexity into clarity. Here’s to the next few years full of clear goals and products that matter.

An impluse to discuss

Perhaps you feel the same way I do: even today, I still find some of the terms in the framework a little strange. No one sprints for four weeks straight and then sprints again for another four weeks straight. A meeting is a meeting and rarely an event. The Scrum Master is the Master of Scrum and not the Master of Hierarchy. And talking about accountability when the world simply says ‘role’ seems overly intellectual. But perhaps that is precisely where the real maturity lies: we understand the language of Scrum without blindly following it. We take the rules seriously without taking them literally. This is how agility becomes an attitude and not a method.

Notes (partly in German):

[1] Tagesschau, 15 October 1995

[2] Lisa the vegetarian. By the way, Linda and Paul McCartney only agreed to appear in the episode when the producers promised them that Lisa would remain a vegetarian in later episodes.

[3] Ken Schwaber: SCRUM Development Process

[4] Ikujirō Nonaka was an economist and organisational theorist who paid particular attention to the acceleration of product development cycles

[5] Hirotaka Takeuchi developed the so-called knowledge spiral and, like Ikujirō Nonaka, is considered a leading expert in knowledge management.

[6] The original text ‘lacks’ some terms that are essential to understanding the process today: Product Owner, Scrum Master, Retrospective, Daily, Definition of Done and Increment.

[7] Prior to the first official version, which was published February 2010, there were already two older, unofficial versions: Ken Schwaber’s SCRUMGUIDE from May 2009 and Ken Schwaber and Jeff Sutherland’s SCRUMGUIDE from November 2009.

[8] Scrum Guide, (Version 1,) February 2010, published by Scrum Alliance

[9] The Scrum Guide (Version 2,) July 2011, published by Ken Schwaber and Jeff Sutherland

[10] The Scrum Guide(Version 3,) October 2011, published by Ken Schwaber and Jeff Sutherland

[11] The Scrum Guide, (Version 4,) July 2013, published by Ken Schwaber and Jeff Sutherland

[12] The Scrum Guide, (Version 5,) July 2016, published by Ken Schwaber and Jeff Sutherland

[13] The Scrum Guide, (Version 6,) November 2017, published by Ken Schwaber and Jeff Sutherland

[14] The Scrum Guide (Version 7,) November 2020, published by Ken Schwaber and Jeff Sutherland

[15] Interestingly, the 2020 version also ‘lacks’ numerous terms that are established in the agile context: velocity, stand-up meeting, definition of ready, story points, traceability, Vegas rule…

[16] How does the content of the different versions change over time? Here you will find an overview with changes.

[17] Robert Briese has published an article in which he recommends a different approach with synchronous dependencies for teams.

We also highly recommend the series of articles by Heiko Bartlog: Agility? We tried it! Does not work!

Would you like to discuss the past and present status of Scrum as a multiplier? Then share this post with your network.

Michael Schenkel has published more articles on the t2informatik Blog, including:

Michael Schenkel

Head of Marketing, t2informatik GmbH

Michael Schenkel has a heart for marketing - so it is fitting that he is responsible for marketing at t2informatik. He likes to blog, likes a change of perspective and tries to offer useful information - e.g. here in the blog - at a time when there is a lot of talk about people's decreasing attention span. If you feel like it, arrange to meet him for a coffee and a piece of cake; he will certainly look forward to it!

In the t2informatik Blog, we publish articles for people in organisations. For these people, we develop and modernise software. Pragmatic. ✔️ Personal. ✔️ Professional. ✔️ Click here to find out more.