Slicing Work – Essential skill for agility

When planning large undertakings, there are two fundamentally different ways of slicing work. Both ways of dividing work are useful for their respective purposes. However, we often lack clarity about these very fundamental relationships, which are relevant for all forms of work, whether we do a lot of planning as in traditional project management or rely on iterative empirical methods.

In our private lives, we are familiar with both ways of dividing work and apply them intuitively in the respective situation. However, we often lose this intuition in large projects. In this article, we look at a relatively simple private project – preparing dinner – to understand the intuitively clear principles and examine their effect in large projects.

The private example project: slicing work in two different ways

Imagine you have invited 20 people to a festive dinner and you are preparing all the food. You naturally want your guests to feel comfortable and you want to meet their personal dietary requirements (vegan, vegetarian, gluten-free, low-carb, etc.). To make things easier, let’s assume the shopping is already done and you have taken a full day to prepare everything. It’s a typical Saturday for your family, with your two kids going to and coming from soccer practice and a playdate with friends.

Of course, you could just hope that everything will somehow work out without planning, but the amount of work is so great that planning is probably worthwhile. You decide to break the work ahead into smaller packages. There are two fundamentally different ways of doing this:

- vertical and

- horizontal division of the work.

The vertical division of dinner consists of a list of all the possible results of the preparation. These are the whole dishes, or individual parts of dishes such as dips or side dishes.

The geometric adjective vertical makes sense if we imagine a cake with several layers: a small but vertical piece of the cake is enough to taste it, while a piece of a single layer, no matter how large, does not give us the opportunity to assess the taste of the cake.

This is what a vertical division of the entire dinner could look like:

Starters

- Greek salad

- Guacamole

- 3 baguettes

- …

Main courses

- Falafel with hummus

- Roast potatoes

- Viennese schnitzel

- …

Desserts

- Tiramisu

- Brownies

- …

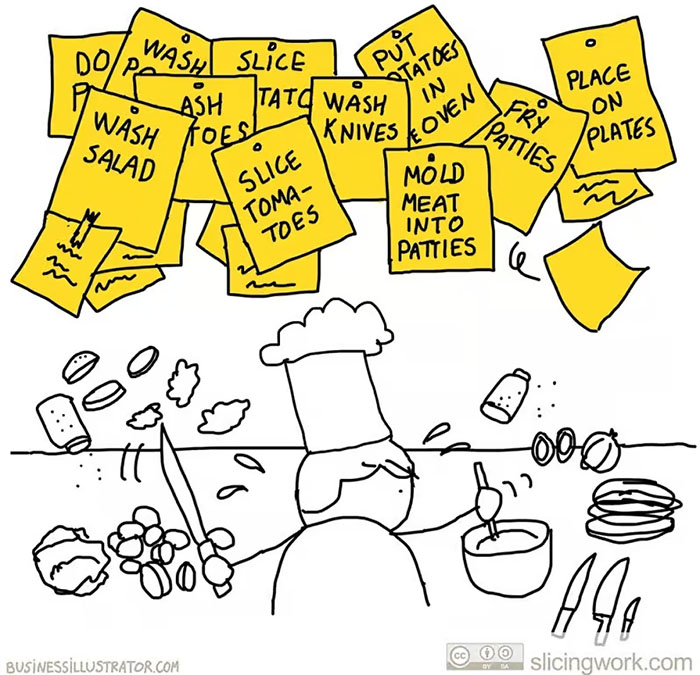

The horizontal division is a list of all the activities necessary to prepare the dinner. There are many more entries here because each dish usually involves many preparation steps:

The horizontal division is a list of all the activities necessary to prepare dinner. There are many more entries here because each dish usually involves many preparation steps:

- 2 heads of lettuce to wash and cut

- 4 cucumbers to wash and cut

- 16 tomatoes to wash and cut

- 3 kg of potatoes to peel, cut,

- fry the cut potatoes and season them

- Boil 2 litres of water and mix with the falafel mixture, shape 40 falafel balls

- …

When we manage work, we have different concerns at the same time, for each of which one of the two lists is more valuable. Let’s look at this in more detail:

Maintain an overview and control scope

Now imagine you want to quickly check whether you have really thought of everything your guests might need. To do this, you need a brief overview of everything that will be on the table. Which list is more useful?

Of course, the vertical division. It is, so to speak, your menu. The horizontal list of all activities does not provide an overview; on the contrary, it is rather overwhelming due to its details.

Suddenly, something unexpected happens: you get an important call and chat a little. And since another parent is unable to help at short notice, you have to drive your daughter to the sports club. It’s now lunchtime and you recognise that you are short an hour of preparation time. Which list will help you now to adjust the amount of food for dinner, cross out dishes and possibly add others instead, so that you can spoil your guests as hoped, even though you will have less preparation time?

It’s the vertical list again.

Both concerns (overview and scope control) of the private example are easy to understand. In a professional context, it’s not quite so simple. When planning larger undertakings, you usually have a large number of clear work packages (horizontal division) and at the same time very few presentable intermediate results or only the one end result. And if you treat your big project as consisting of only a few (but large and complex) dishes, then you lack an overview and the ability to control the scope.

So ask yourself about your projects: When will there be something for the beneficiaries of the project to try out or evaluate? And how many such intermediate results are there?

Efficiency as a reason

There is a fixed, non-negotiable number of dishes for your dinner: 10. Which list helps you to prepare these 10 dishes in the least amount of time?

The horizontal division is valuable here. It helps you to recognise where it is worth combining activities. For example, you can peel the potatoes for all three dishes or wash and cut all the tomatoes for several dishes in one step.

Efficiency gains are often the reason why organisations create a long, detailed list of activities.

But what happens if you end up with fewer dishes than you originally thought, because you are forced to do without two of the three planned potato dishes? Then you have peeled potatoes very efficiently, but you will only be able to use some of them.

At this point, you recognise a very important and fundamental principle of work management:

If you optimise for maximum efficiency, you lose flexibility.

This applies to both dinner and work in large organisations and is completely independent of whether we work iteratively empirically or classically.

Delegation and responsibility

Just imagine you feel under pressure and would like other people to help you with your work as independently as possible. Which task from which list could you assign to a friend who is good at cooking independently? And which task could you delegate to your eight-year-old daughter?

It would certainly be helpful if the friend took on an entire dish, e.g. fried potatoes (vertical list entry). But unless your daughter has just appeared on Top Chef Jr., you will probably hand her the potato peeler and ask her to stand over the sink so that there is no big mess. And even then, you should briefly check the quality of the peeled potatoes and give feedback if necessary. We delegate intuitively, depending on the competence we attribute to the person or group to whom we delegate.

This has far-reaching consequences in both the long and short term, which we should be aware of.

Here is a possible short kitchen conversation (from my household) that makes the most important context clear:

A: ‘Can you please cut tomatoes for the hamburgers?’

B: “How thin do you want them?’

A: ”You’ve eaten it yourself many times. How thin do you like them?’

The point is, when you give individuals or entire teams horizontal tasks to do, you automatically do not invite them to think about the overall result and take responsibility for it. However, responsibility automatically arises when someone takes on an entire result.

When an organisation relies on the self-organisation of teams or individuals, it is absolutely essential that vertical tasks be delegated to them.

And how does someone who has been given a vertical or horizontal task improve?

If your daughter repeatedly receives helpful feedback on how to peel potatoes better, she will become better at it. She will become a better potato peeler. That’s fine, but no matter how good she gets, it won’t make her someone who can independently prepare fried potatoes.

If, on the other hand, your friend repeatedly prepares fried potatoes and receives feedback on them, he has completely different creative freedoms – he can experiment with the spices or the frying to create his own perfect fried potatoes. He improves his cooking skills more holistically.

Whatever receives feedback improves, but only that.

These relationships are particularly important for managers who have the impression that their employees are not thinking for themselves and want their work to be constantly coordinated. To escape this micromanagement trap, you have to start delegating vertical work results and expect that it will take a few attempts before the ability to organise themselves emerges.

Measuring progress

How do we know if we are really making progress in our work or just staying busy without actually getting anything valuable done?

Imagine you are making tiramisu for the very first time. You use a recipe – a list of ten horizontal steps – and tick off the tasks you have already completed. Eight out of ten steps are done. Does that mean you have already made progress? And if the respective steps take about the same amount of time, would you say you are about 80% done?

Well, if you’re anything like me, you’ll find that at the ninth step – dipping the ladyfingers in coffee – everything you’ve prepared in the previous eight steps can go wrong. Everything is soaked and mushy, and instead of a tiramisu, you end up with a soft mass that your friends and family might eat but an external customer would never pay for.

When you are doing something new and therefore unpredictable, it is important to understand that progress is only assured when the result of the work is available. So if you want to measure progress in unpredictable undertakings, you need a lot of small vertical work results.

It is different when you are doing something for the tenth time. Then you know all the possible surprises. If I prepare a tiramisu today, I can be sure that I am almost finished after eight steps. For familiar projects, we can rely on finished horizontal work steps as a measure of progress.

If an organisation has only defined a few intermediate results or a vertical end result for a project, everyone involved will be in the dark for a very long time or will rely on fake measurements (or, as they say in lean start-ups, ‘vanity metrics’) of progress based on completed horizontal tasks. As a result, important decisions are overlooked during the course of the project and unpleasant surprises are inevitable in the end.

Summary: Slicing work

Work can be sliced in two different ways: horizontally and vertically.

Both slicing methods are helpful. Depending on what we want to achieve, we need one of the two slicing methods. The vertical slicing helps us to

- keep an overview and control the scope of the work

- delegate responsibility

- enable self-organisation and promote the creative growth of our employees

- measure progress when dealing with tasks when we have to expect surprises or unpredictability.

The horizontal division helps us above all in the optimisation of the efficiency of our work.

Notes:

Would you like to talk to Anton Skornyakov about slicing work or about self-organisation and adaptability? Then simply get in contact with him via his website. And if you would like to read more on the subject, then take a look at the book The Art of Slicing Work: How to Navigate Unpredictable Projects by Anton Skornyakov.

If you like the article or want to discuss it, please feel free to share it with your network.

Anton Skornyakov

Anton Skornyakov is a Certified Scrum Trainer® and Agile Coach from Berlin. As a former serial founder and graduate physicist and mathematician, he now helps organisations on their way to adaptability and self-organisation. Anton is passionate about applying the tools from the agile world in public administration, in non-profits and in other areas outside of product development.