What makes decisions so difficult?

Our lives are shaped by decisions, both big and small. Salted or unsalted butter? Crap, I had xyz yoghurt on my shopping list. Can I get a different one if xyz is out of stock? And do I just decide that on my own or do I discuss it with my partner first?

In our private lives, making the wrong decision can lead to an awkward silence at the breakfast table. In a business context, however, the consequences are often much more far-reaching, which is why it makes sense to prepare decisions well. If it weren’t for psychology, which repeatedly makes it difficult for us to make decisions.

Decision aversion or decision procrastination

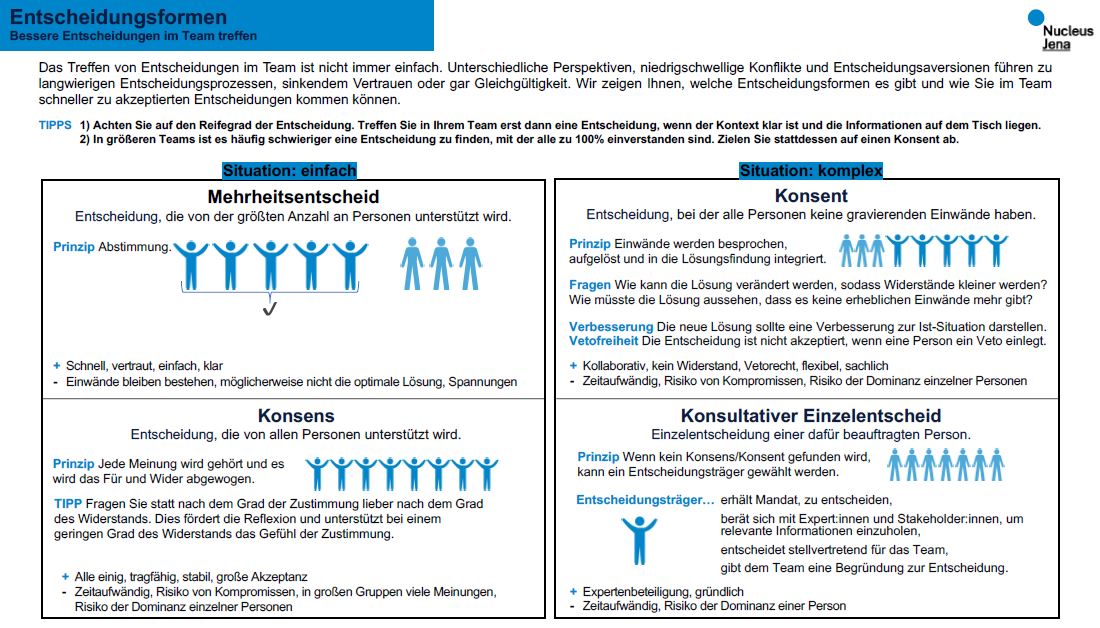

Many people tend to postpone decisions. They want to think about the issue again, wait for more information, or possibly consult with some team members again. The more far-reaching the (business) decision is, the more likely it is to be postponed. Of course, hierarchies and decision-making processes in the company also play a role, as the following German-language graphic by Nucleus Jena illustrates [1]:

But basically, the worst thing you can do is not make a decision. Because if you decide, you can lose. If you don’t decide, you’ve already lost.

As I recently observed quite banally during a quiz duel: the presenter had given a final deadline of 10 seconds, the team of candidates could not agree – time’s up, no points.

The internal conflict: decide in favour of one thing and against another?

In the endeavour to make a well-founded decision from a multitude of possibilities (if possible, all conceivable ones), one often creates a maximum of uncertainty for oneself through the self-imposed diversity of alternatives. In doing so, factors often become determining determinants that, in contrast to those that one selects, should act as guard rails: Often they are factors that one cannot influence within the company. Budget, schedule, quality.

Here, too, several factors play a role: On the one hand, the decision is complicated by the fact that ideally you want everything. The perfect solution. The result is an inner conflict in which you strive for it, even though you know that this solution does not exist. And often it is not the joy of the decision made and the solution chosen that dominates in your mind, but the (phantom) pain of having decided AGAINST the alternative. That this might have been better, even though the decision was made to the best of one’s knowledge and belief.

A feeling of insecurity that well-thought-out product marketing has been exploiting for years to reinforce the customer’s purchase and to convert the ‘post-purchase dissonance’ into conviction and, ideally, brand loyalty: The letter or email that congratulates the buyer after the purchase, once again highlights the product benefits and, if applicable, cites test reports. Basically, a controlled post-rationalisation that provides positive confirmation. And does not lead the decision-maker to view the alternatives retrospectively as inferior in order to reinforce the decision. A much more positive mindset for future decisions.

Something that decision-makers in companies or decision-making bodies should also be particularly aware of: we have made this decision. It will do our company good. We have not made it lightly. We have made it out of conviction. And we stand by this conviction.

Cognitive disruptors

In principle, every person thinks long and hard before making a decision, whereby the extent of the decision and its implications are a sufficient factor (new pair of socks vs. new cash register system in food retailing). Nevertheless, in the context of psychology, other individual factors play a role that unconsciously steer our decisions in a certain direction and make them appear only seemingly objective.

a) Confirmation bias

A prime example of this is the so-called ‘confirmation bias’, a term from cognitive psychology.

Essentially, it describes a funnel that we create in the decision-making process, which leads us to identify, select and ultimately interpret the information necessary for the decision in such a way that it matches our own expectations. We speak here of a perceived freedom of choice, which we ourselves limit or even sabotage. A kind of cognitive dictatorship. This can also be counteracted by becoming aware of this sabotage and deliberately seeking out counter-opinions and divergent perspectives and actually incorporating them into the process.

b) Loss aversion

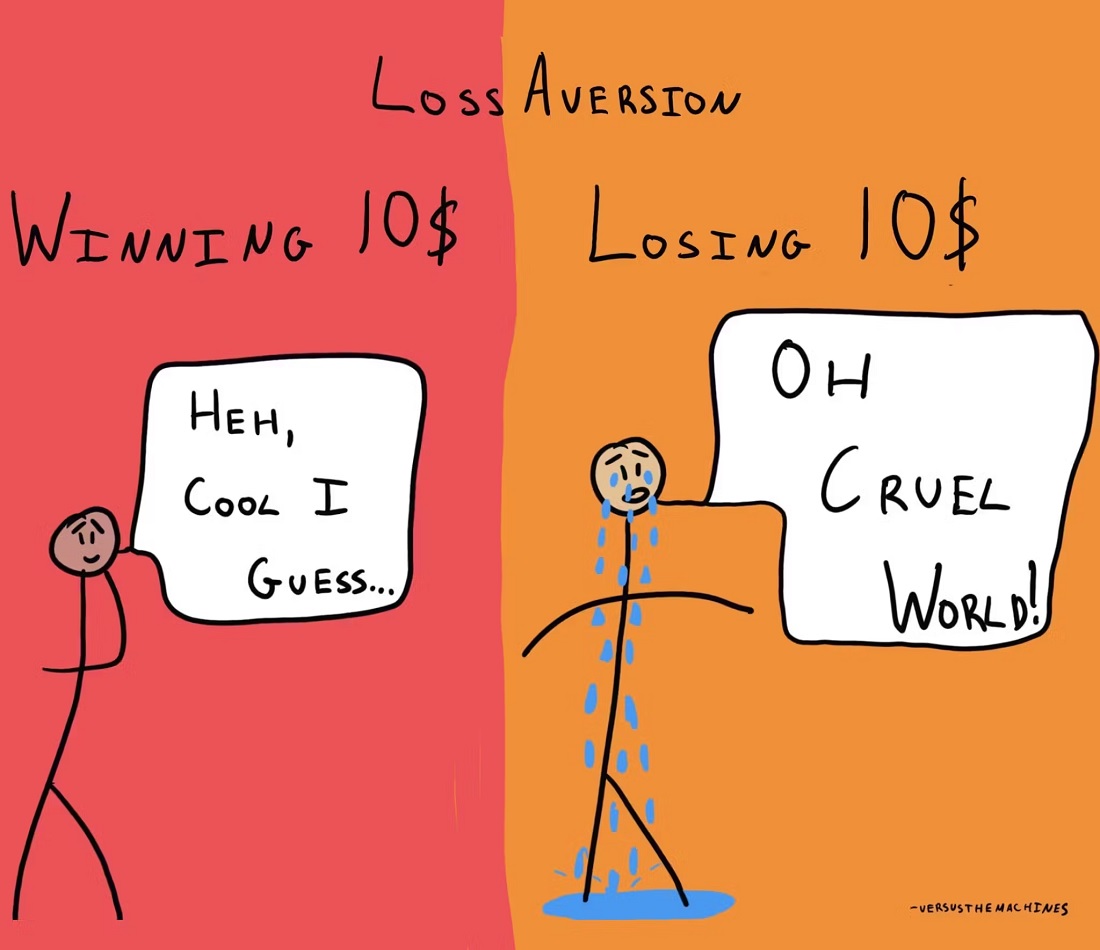

Another factor is what is known as loss aversion, i.e. the greater weighting given to a negative event compared to a comparable positive event, as illustrated very clearly here by The Decision Lab [2]:

Here, too, a reversal of thinking must be created in the decision-making process that outweighs the positive aspects of the decision taken over the potentially negative aspects of the decision against the alternative. Rejoicing in the decision taken and its positive effects. And not just a backward-looking ‘if only…’ attitude, although a review of the decision, in particular the correct implementation of the decision, is of course imperative.

c) Groupthink according to Janis

In 1982, the psychologist Irving Janis coined the term groupthink. He defines groupthink as ‘a way of thinking that usually occurs when a group’s need for harmony in decision-making is stronger than the realistic consideration of alternatives.’ [3]

We also know this behaviour from the world of work: a compromise is reached in order to bring about a decision that is capable of winning a majority.

This can, of course, be done on the basis of a points system, but awarding points is also a subjective process. And if there is a dominant and articulate personality in the group, they can control the process and steer it in a certain direction.

Conclusion: the art of decision-making – conscious consideration, confident action

Making decisions is rarely easy, but they are the driving force behind our actions – in our private lives as well as in the business context. We often hesitate due to uncertainty or allow ourselves to be influenced by psychological mechanisms such as confirmation bias, loss aversion or groupthink. Recognising these thought traps helps us to make more conscious and informed decisions.

In simple situations, majority or consensus decisions help. For complex issues, consultative individual decisions or decisions that nobody has serious objections to are useful.

Perfect decisions are rare – but instead of being paralysed by the fear of making the wrong decision, it is worth focusing on the positive effects of the choice made. Ultimately, it is not only the decision-making process that counts, but also the conviction with which you stand behind a decision – and the joy of having made it.

Notes (partly in German):

Would you like to discuss decision-making in marketing or communication and marketing strategies with Carsten Riechert? Then feel free to contact him on LinkedIn.

[1] Nucleus Jena: Entscheidungsformen

[2] The Decision Lab: Loss Aversion

[3] Online Lexikon für Psychologie und Pädagogik: Groupthink

If you like the article or would like to discuss it, please feel free to share it in your network. And if you have any comments, please do not hesitate to send us a message.

Carsten Riechert

Carsten Riechert has a degree in Business Administration and has been developing communication and brand strategies for companies as a marketing specialist since 1998. Since becoming self-employed in 2017, he has also focused on change processes and new forms of project management. He has been passionate about cinema and films ever since he saw ‘Godzilla und die Urweltraupen’ at the age of 6.

In the t2informatik Blog, we publish articles for people in organisations. For these people, we develop and modernise software. Pragmatic. ✔️ Personal. ✔️ Professional. ✔️ Click here to find out more.