Democracy in strategic decisions

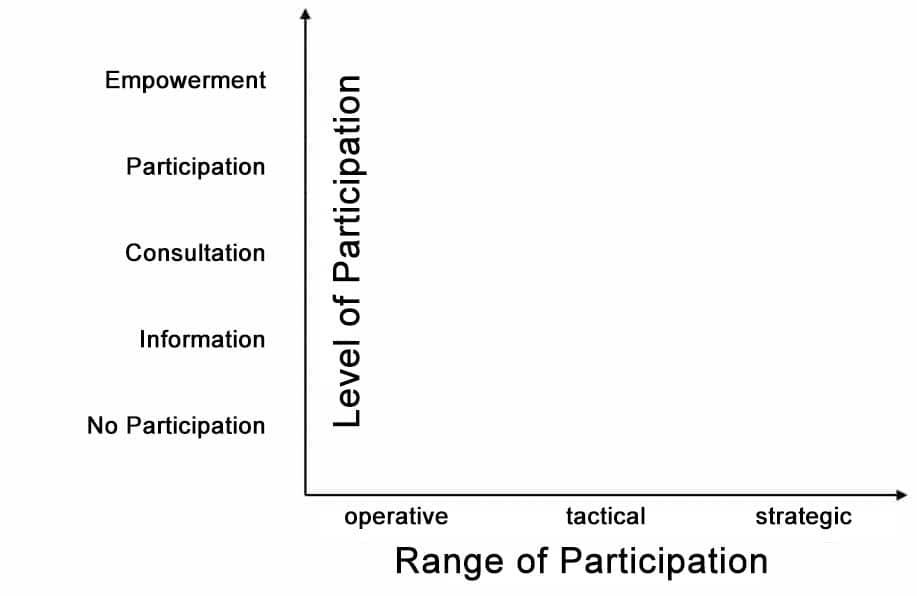

It gets more impressive when there are 50 or 300 people. Then, after the most obvious question about the number of people involved in the decision-making process, there is a second important question: The question of the range of participation. To understand this, here is a simple chart that illustrates the dimensions of corporate democracy in a simple way:

The interplay of degree of participation and participation range.

This should become immediately clear: Organisations are not simply democratic or not democratic. Rather, the whole is a continuum with different manifestations. There is a considerable difference in the degree of participation in whether decisions are taken or not

- in the consultative individual decision,

- in a socio-cratic consensus procedure within a manageable group,

- or as a mass decision of a whole workforce with a decision market.

And in terms of range, it is a fundamental difference whether employees are only allowed to determine their own daily work (operationally: working time, location, means … ) or whether they are already allowed to make more important and fundamental decisions (tactically: team recruiting, project staffing and selection …) or even make the most far-reaching decisions together (strategically: business models, strategy development …). This brings us to the topic of this article: Democracy in strategic (corporate) decisions.

The more complex, the more participative

Just as it is not impressive when a handful of people make participative decisions at work, so it becomes more meaningful with increasing complexity to include several perspectives in the decision. Why is that so?

Simply put, it is about using more heterogeneous data and information for complex decision making in order to cope with (increasing) complexity. To put it another way: With the increasing dynamics and complexity or in short: Dynaxity of our (economic) world, decisions on a relatively small, homogeneous database are becoming increasingly dysfunctional. Fifty years ago, when a management team of two, assisted by strategy consultants, developed the next corporate strategy, this was understandable in the context of more stable markets and simpler political conditions (e.g. the clear division into East and West blocks) and even slower and simpler networking before the Internet, as we know it today. However, it should also be noted that participation would have been an interesting option in the past due to individual motivational psychological aspects of employee participation in strategy development.

This connection between the complexity of the business environment and participatory, democratic strategy development finds its information-theoretical justification in Ashby’s Law:

“A (controlling) system can compensate for more disturbances in the control process the greater the variety of its actions.”

This is precisely why we humans, as the most complex way of life on earth at present, are the only living beings that have successfully spread across the entire world from permafrost to desert regions: our action is greater than that of a polar bear or a rattlesnake (exceptions confirm the rule).

So if the complexity and dynamics of the environment increase, it is not a wise idea to demand a reduction in complexity in the internal relationship of a company. The exact opposite is the case: as the complexity of the environment increases, the complexity (of information processing) within the company should also increase. This can be formulated pragmatically: The more different perspectives of the employees are included in complex decisions, the more likely the result will be a functional response to the current challenge.

Strategy development – it couldn’t be more complex

The development of a future strategy is the most complex decision to be made in organisations. For this, a sufficiently valid and precise vision of the future must be developed, on the basis of which the actors in the company then develop a strategy that fits their organisational purpose. Strategic decisions reach farthest into the future and have to absorb more uncertainties and varieties than when it comes to the next recruiting or the next project staffing. And this look into the future is already more difficult than it was in the past and is likely to become even more complex in the future.

It’s a mystery to me how the fundamentally very limited top management of the executive board comes up with the idea not to include all the diverse perspectives of employees from the most diverse functional areas. After all, as already mentioned above, firstly, sufficiently precise and reliable future scenarios are required in order to be able to develop the actual strategy on this basis at all. It is similar to the medical anamnesis, the admission interview and the subsequent diagnosis. If there is sloppiness, the therapy can at best be accidental, but will generally fail. Secondly, a comprehensive view of the various functions and areas of the company is needed. A sales representative has a completely different view than someone from Controlling or a member of Research & Development.

Managing directors and board members with an affinity for technology could now reply: Nonsense, we only need big data and artificial intelligence and do not have to involve the workforce. Really? I have just one question: If that were the case, why would IBM, as one of the largest Big Data developers and providers since 2011, need a full six years to finally achieve an increase in turnover – which isn’t even particularly overwhelming? Why didn’t the stock of this company go through the roof with a Watson who, as you know, left human top players far behind at Jeopardy in 2011?

Information theory AND motivational psychology

From two perspectives it therefore makes sense to invite employees to participate in joint democratic strategy development (Attention: participation must of course be voluntary!):

- Firstly in the sense of business success: the company wants to be successful in the future market with a successful strategy. To this end, it is helpful to include the numerous perspectives, experience and knowledge of the employees. This is the information-theoretical argument.

- Secondly in the sense of corporate culture: the company probably wants to develop, establish and maintain a culture in which employees like to perform and contribute their creative potential. To this end, it makes sense to enable all employees who want to help shape the company to do so. This is the motivation-psychological argument.

The future of entrepreneurial strategy development

Finally, I would like to take the liberty of taking a bold look at the big picture of the future: I recently came across the World Values Survey. This is a large-scale longitudinal study on the development of democratic values in the international community that has been running since 1981. The exciting thing: Overall, the spheres of values in many countries are developing in the direction of more democracy and empowerment. In this respect, in the long term it is to be expected that employees will increasingly be interested not only in being spectators of their own working world, but also in actively shaping it. If this is true, the future of entrepreneurial strategy development lies in democratic participation.

Notes:

Dr. Andreas Zeuch has published several articles in the t2informatik Blog, including

Dr. Andreas Zeuch

Dr. Andreas Zeuch works as a freelance consultant, trainer, speaker and author. He accompanies companies on their way to more empowerment and corporate democracy. His books “Alle Macht für niemand. Aufbruch der Unternehmensdemokraten” and “Feel it!: So viel Intuition verträgt Ihr Unternehmen” are bestsellers and provide many practical examples.