OKR pitfalls: Prioritise, but with focus

In product development – especially agile development – there are some methods and approaches that, although highly praised, are far from being the panacea they are sold as in practice. When it comes to prioritising projects, one method is at the top of the list: Objectives and Key Results (OKR). OKR can be helpful, but often there are problems in their application. In this article, I explain these pitfalls and how to avoid them.

But before we go into these details, the first question to ask is: Why is prioritisation important?

There are typically many (product) ideas – in abundance. However, what is usually not available in abundance is the capacity to implement these ideas. It is usually the limiting bottleneck in product development.

For this reason, we have to decide how we will use this capacity. There are many prioritisation methods, but one is by far the best known: Objectives and Key Results. [1]

How does it work?

The OKR method in brief

Essentially, OKR consist of two basic concepts:

- Objectives: These should be ambitious goals, such as ‘We are tapping into a new customer segment.’

- Key Results: They belong to an objective and should be measurable steps to achieve it. For example, for the above objective, a key result could be: ‘We are winning 4,000 new customers from this segment who use our product A at least three times.’

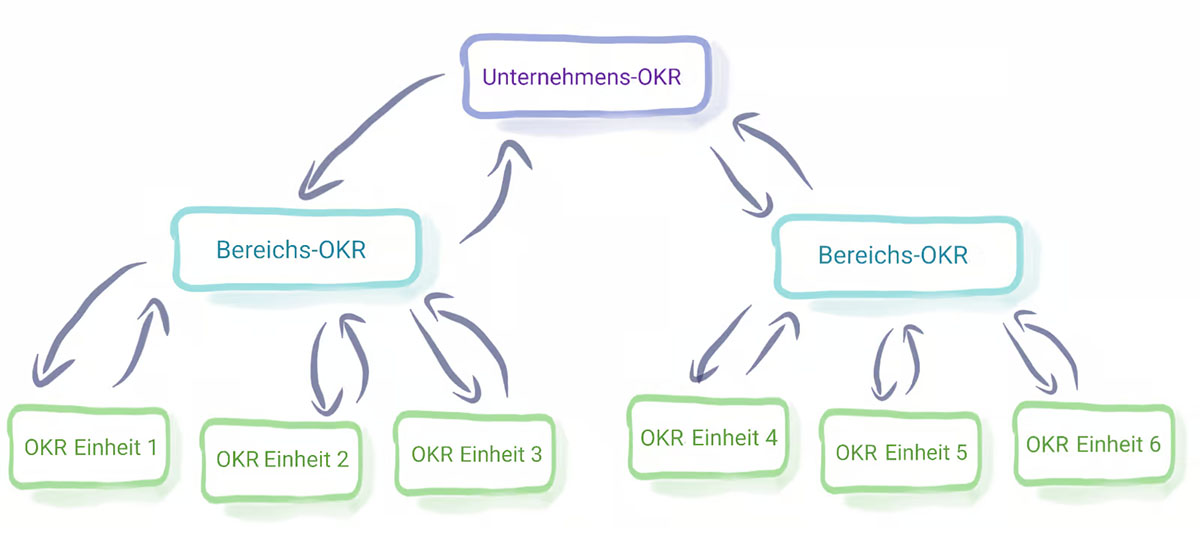

These Objectives and Key Results can exist at several organisational levels.

Superordinate levels set the strategic direction with their OKR. Subordinate levels, in turn, should support the Objectives and Key Results of the superordinate level with their OKR, or contribute to them.

In practical terms, this means that the company OKR is supported by departmental OKR, which in turn are supported by the OKR of their respective sub-units.

Figure 1: The OKR method

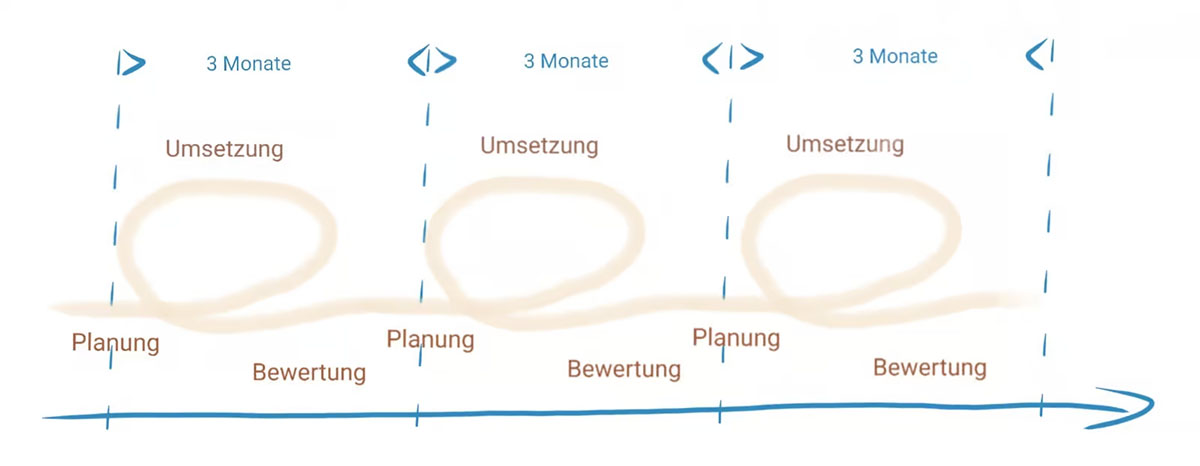

OKR are set in advance for a defined period of time – typically three months – and then worked on. Ideally, progress is reviewed during the cycle, but at the very least at the end of it. Based on these findings, new OKR are planned for the next cycle.

This process is designed to ensure that objectives are clear, outcomes are measurable and teams are aligned with common goals. What could possibly go wrong?

Typical pitfalls when using OKR

I see a few typical pitfalls when using OKR time and again:

Excessive coordination effort

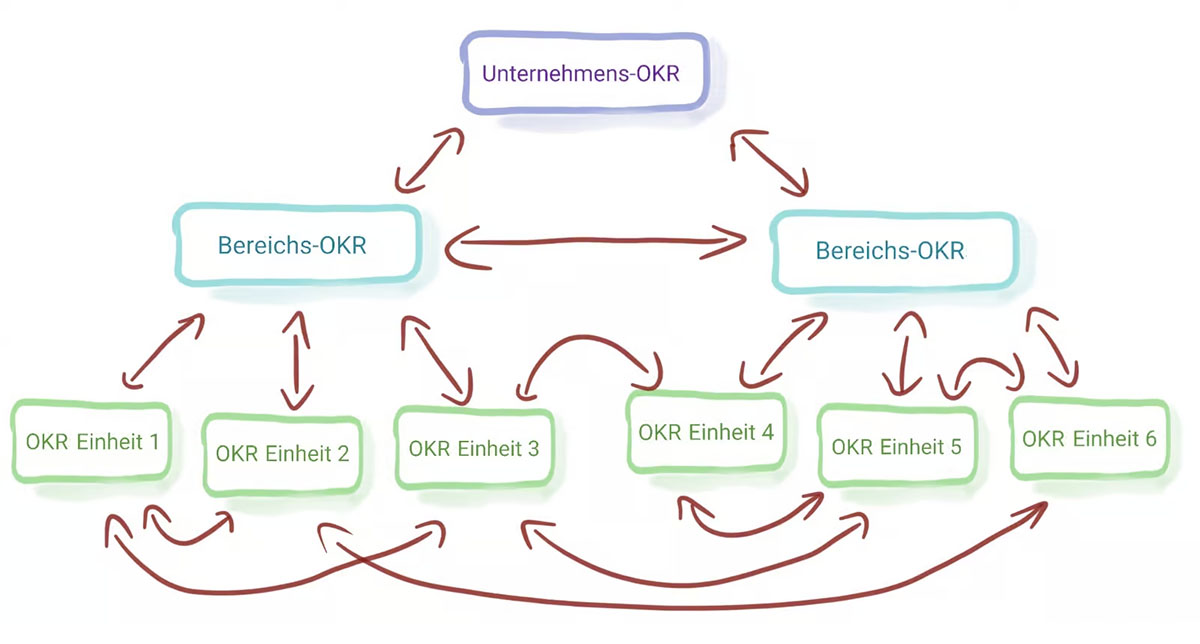

Preparing and planning OKR can require a tremendous amount of effort.

If organisational units want to support overarching goals, e.g. ‘We are opening up a new customer segment’, the approaches they take to support this goal can vary greatly. In a non-trivial organisation, these different approaches will each require support from other units.

Therefore, all units spend a lot of time preparing, presenting and coordinating their ideas with others before each cycle. This happens mainly when projects are planned instead of objectives – which should be avoided at all costs. I have seen cases in which the entire company was busy for two weeks just preparing the next OKR.

Figure 2: OKR coordination effort

Lack of focus

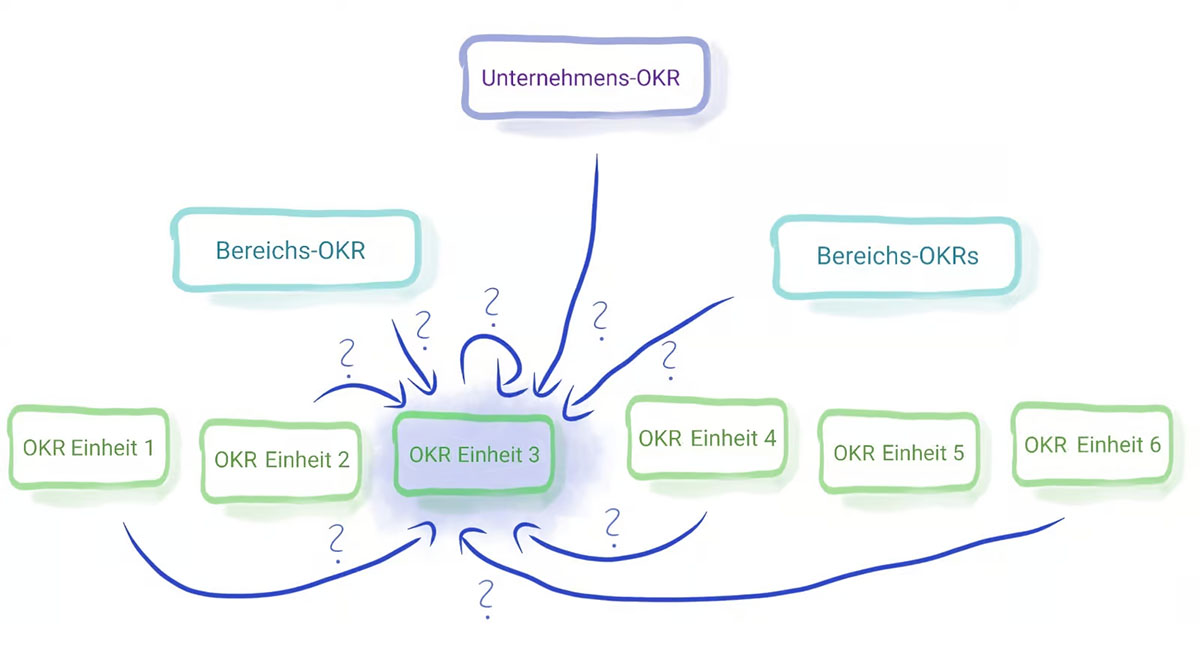

Another typical problem is the loss of focus during the OKR cycle.

Let’s assume that each team is already working on its OKR in a focused manner. Now, a team discovers a dependency between the OKR and offers another team support. The argument is usually: ‘You have to help us – the topic is in the OKR!’

The larger the organisation, the more dependencies, the more requests – and the less focus for each team.

Organisational units or teams often make life difficult for themselves by planning far too ambitiously. If five goals, each with three to five key results, are planned for three months, that may be just too much.

I once saw an example where the walls of an entire room were covered with the OKR of all the teams. Does that create clarity and focus?

Figure 3: Lack of focus with OKR

Absent agility

OKR look very agile in theory, but often aren’t in practice.

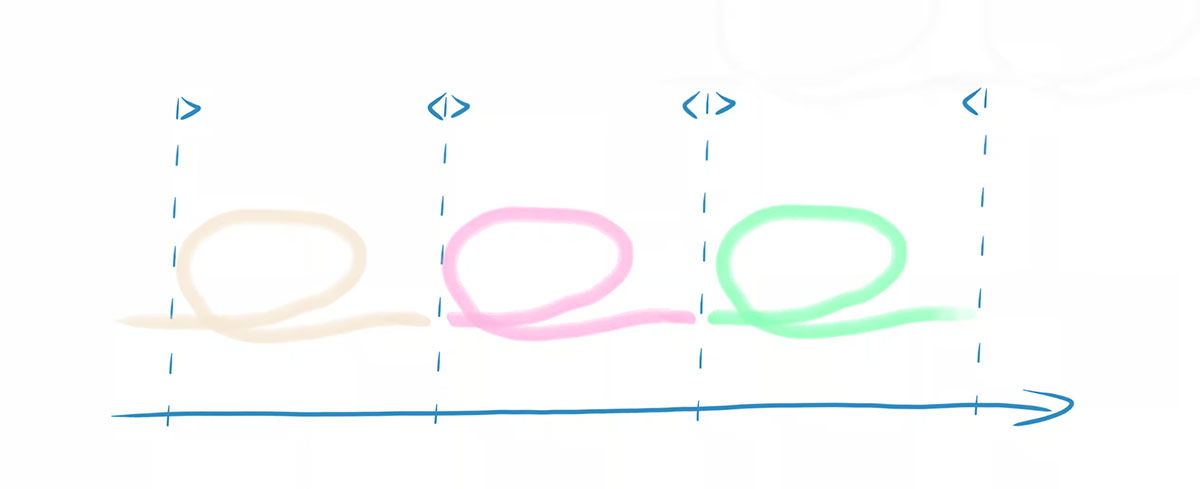

Figure 4: Agile ORK cycles in theory

How many undertakings last exactly three months? Very few.

But initiatives are often simply dropped after three months. However, other stakeholders (who may have come away empty-handed in the last cycle) really want to see their requirements prioritised.

Figure 5: A series of mini waterfalls

The result: products are not optimised, a product-market fit is not achieved and long-term innovation suffers in favour of short-term priorities.

That is not agile.

How can it work better?

OKR don’t have to be so disastrous, though, and they can definitely work.

The following tips will help you use OKR more effectively:

- Limit the number of Objectives and Key Results – and do so strictly (~3 are reasonable, but this varies depending on the context). If, contrary to expectations, time is still available at the end of the cycle, no one will be angry if the team delivers more than planned.

- For each objective, determine a responsible person early on who will coordinate the goal, the corresponding Key Results and all dependencies – over the entire period.

- Plan for a maximum of 60% of capacity. The remaining capacity is needed for operational business, unexpected requests or maintenance and bug fixing. In the best case, there is time to support others or deliver more.

- Plan goals, not projects! A really common negative example is planning projects in OKR. Objectives and Key Results are not meant for this and it is also the wrong approach. If the only thing that matters is delivering the project, then in the end it doesn’t matter whether any benefit is derived from it. The project has been delivered, so everything is fine!

And last but not least, objectives should remain stable over the long term. They can remain unchanged over several cycles until they are achieved or deliberately deprioritised.

What Objectives and Key Results cannot achieve

Furthermore, some misunderstandings about OKR persist, which are also fuelled by the fact that they are often touted as a panacea.

Objectives and Key Results do not replace:

- a strategy,

- a product development process,

- a planning and design process or

- a conflict resolution process.

An organisation needs all of these in addition. OKRs only define priorities: ‘what is important.’

Another thing that is often misunderstood is that objectives and key results do not provide a solution design. They clarify the “what”, not the “how”. A solution design follows later – otherwise we would be prioritising projects again.

This also means that OKR can only help with coordination between teams to a very limited extent. Since the solution design only follows later, the dependencies, e.g. on other teams, are still unknown during planning. As long as I don’t know what I want to develop, I can’t know which teams will be affected.

Conclusion

Objectives and Key Results are not the panacea they are sometimes made out to be. That doesn’t necessarily mean they can’t be used. If you have been working without prioritisation up to now, OKR is certainly a step forward. They are equally helpful when individual departments or a small business organisation use them.

However, in larger companies at the latest, you should take care to avoid the pitfalls described.

In no case should this article discourage you from prioritising. Without prioritisation, an organisation works on the wrong topics, on too many topics, on conflicting topics, in other words: inefficiently. No company can afford that. OKR with the tips presented here is a better alternative!

Notes:

[1] Here you can find more information about ORK benefits, tips to get started and questions from the field.

Jan Hegewald blogs at https://www.agil-gefuehrt.de about modern leadership and agility. His newsletter The Tech Impact Uplift describes how tech organisations can deliver more value to customers. You can easily get in touch with him on LinkedIn.

If you like the article or want to discuss it, please feel free to share it with your network.

Jan Hegewald has published more articles in the t2informatik Blog:

Jan Hegewald

Jan Hegewald is VP Engineering at Rabot Energy in Berlin. Previously, he was VP Engineering at Taxdoo, VP Engineering at SumUp Ltd., Director of Engineering for Product and Category Experience at Zalando SE and Head of Technology B2B at idealo internet GmbH. Before that, he spent many years designing, building and implementing custom IT systems for critical core processes at large companies. He also advised a wide range of clients on project, programme and portfolio management methods.

In the t2informatik Blog, we publish articles for people in organisations. For these people, we develop and modernise software. Pragmatic. ✔️ Personal. ✔️ Professional. ✔️ Click here to find out more.