Agility was just the beginning

Expand the table of contents

On the way to becoming a high-performance organisation

No one is interested in agility anymore!

According to a study by the Karlsruhe University of Applied Sciences, a slight majority of German-speaking companies have introduced agility. [1] However, the adaptation rates of German-speaking companies are far behind those of the USA, China or even India. This is not surprising when you take a closer look at the study data. In this case, ‘introducing agility’ simply means applying agile methods such as Scrum or Design Thinking. These methods are more or less standard in technology-related disciplines. It is therefore rather surprising that only a slight majority of companies in German-speaking countries use such methods. Conversely, it can be assumed that so far only very few have achieved the goal of organisational agility.

Although the spread of agility is far from complete and there is still a lot to be done in companies in this regard, the trend seems to be flattening out, if not disappearing altogether. Many organisations rate the topic much lower than they did between 2016 and 2022. As a result, less and less investment is being made in the organisational development that this requires. Why is that?

Reasons for the declining interest in agility

Many organisations cite the fact that agility has not delivered the hoped-for added value as the main reason for this decline in investment.

However, to say that agility does not add value would be to throw the baby out with the bathwater. There are many reasons why many organisations have not been able to realise the added value they had hoped for. The reasons for the declining interest can be found in a number of areas:

Reason 1: No holistic transformation

Many companies are content with the introduction of agile methods such as Scrum and Kanban. What is missing is a more profound transformation of systemic conditions and the underlying organisational culture. However, since companies are complex organisational systems that can only create added value through the interaction of several teams, the added value of individual teams that do Scrum or Kanban is very limited.

Reason 2: No context-adequate application

In the hype phase of agility, everyone introduced agile methods everywhere. This was supported by a glut of training and consulting services on the market that may have explained how agile methods could be introduced. However, organisations often introduced dogmatic agile practices without taking into account the conditions and restrictions of the organisational context. And so agility was misunderstood and introduced incorrectly in many organisational units.

Reason 3: Lack of patience

The transition from a traditional to an agile organisation is disruptive if it is holistic. This means that collaboration in an organisation has to be learned from scratch. Be it the communication dynamics in a team. Taking responsibility. Dealing with tools. New meeting structures. Leadership roles. The understanding of leadership roles. values that underpin the work. This fundamental change is initially unsettling for any organisation. It is therefore almost impossible to make this change without a decline in productivity at the beginning of the transformation journey. This requires patience and foresight on the part of the decision-makers in order to endure this logical dip in productivity.

Reason 4: Lack of empowerment

As mentioned, a holistic agile transformation is a disruptive change for an organisation. Therefore, it requires intensive support at three levels to ensure that this organisational development is successful:

- At the individual level, enough training and coaching is needed to establish a common basis and understanding within the team or organisational unit.

- At the team level, empowerment, coaching and consulting are needed so that team members can work together effectively in this new paradigm.

- And at the organisational level, empowerment, consulting and systemic adjustments are needed so that the new paradigm can be scaled beyond the individual teams.

Hardly any company has invested in the necessary measures at all three levels.

Reason 5: Persistence of Tayloristic management practices

As with any disruptive organisational change, an agile transformation also requires a fundamental change in leadership patterns and leadership roles. A core element of agility is that decision-making responsibility is transferred to those roles in the organisation that have the best competence for it. This has the consequence that the concentration of power in the classic management roles is broken up in order to optimise decision-making and thus accelerate the organisation’s ability to act. However, it is not surprising to find that only a few decision-makers have taken this step of relinquishing some of their power, which would be necessary for an agile transformation.

Have we solved a problem with agility at all?

One of the drivers behind these various causes of failure is that agility was introduced as an end in themselves in many cases. And not as a means to an end. Even if it was perhaps initially conceived differently. So, to find out what is left of the agile movement and how it should develop, we must first reflect on the problem that agility originally set out to solve.

Many people see the beginning of agility as dating back to 2001 and the publication of the Agile Manifesto, which was intended to improve software development. Accordingly, many also see the origin of agility in IT, which, against the background of increasing change dynamics and complexity, was looking for ways to do justice to the digitalisation trend that has actually occupied all companies seeking to survive over the past almost 40 years.

Even if this is not wrong as an observation, the core is even deeper. Agility was already taken up in research in the 1950s, as it was increasingly found that the prevailing management theory undermined the ability of organisations to change. Anyone who has seen the film Modern Times by Charlie Chaplin will have a good idea of the organisational model that the doctrine of the time, known as ‘scientific management’, proclaimed: a few clever managers at the top of the hierarchy think. The rest work on the assembly line. However, the paradigm of scientific management has survived well beyond the 1950s, even though more and more organisations have found that the pace of change is accelerating, customer needs are becoming more individual and the world more complex.

In the second half of the 20th century, Warren Bennis and Burt Nanus, two economists at the University of Southern California, described the basic principles of what would later become the widespread VUCA concept. This acronym quickly spread and helped many in the business world to understand that market conditions had changed from those of the last century and that an innovation in organisational management was therefore needed. In this sense, the agile movement can be seen as an answer to the problem that the scientific management approach no longer works in today’s market environment.

So we can say that the original problem that agility tried to solve was an innovation in how organisations are managed. Namely, away from the scientific management approach, which in a globalised, dynamic market meant that companies were too slow for this so-called VUCA world.

In the meantime, a new acronym, BANI, is trying to establish itself. While VUCA stands for volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity, BANI is made up of the words brittle, anxious, nonlinear, incomprehensible. Jamal Shahin, the inventor of the BANI term, does not contradict the VUCA concept, but rather tries to use it to describe today’s complexity and dynamics more precisely. In doing so, he takes into account more strongly than the VUCA concept the consequences of increasing global networking and ubiquitous digitalisation: namely, a highly dependent and barely transparent market dynamic.

The consequences of this BANI world were evident, for example, in March 2021 when a large container ship got stuck in the Suez Canal, blocking all shipping traffic for six days. The economic cost of this blockage was estimated at around 60 billion US dollars. Another example was the supply chain bottlenecks in 2022 that resulted from the COVID pandemic and were partly responsible for a global increase in inflation.

These developments show that the pace of change and market complexity will continue to increase in the future. Although we can see a political shift towards more local protectionism in many countries, and since the coronavirus outbreak, highly fragile supply chains have also been scrutinised and in some cases made more resilient or local. But digitalisation cannot be stopped. And digitalisation not only connects us globally. It also means that more and more complicated tasks are being automated, leaving people with increasingly complex work. With the spread of artificial intelligence, this trend will accelerate even further.

We learn from this that a return to the scientific management approach is not expedient. This century-old organisational theory worked at a time when the majority of workers on the assembly line performed mindless tasks and companies had to optimise primarily for efficiency. However, the trend is moving in the opposite direction. In a highly complex, rapidly changing economy, doing the right thing is more important and challenging than being perfectly efficient. Accordingly, there is still, or rather, increasingly, a demand for an organisational model that meets these challenges.

If not agility, then what?

So if we focus on the core problem, that a new organisational model is needed for the VUCA or BANI world, then we can conclude: Much of what the agile movement has proclaimed is an adequate answer to this problem. It is also important to remember that much of it did not just emerge in the last 5 to 10 years, but draws on many years of research and practice: an important basis was the work on lean management (from around 1980). Systemic organisational theory (from around 1990) and modern approaches from leadership research (from around 1990) and innovation management (from around 2000) were also important sources of inspiration. In addition, there are many decades of experience in modern software development, which is increasingly becoming a defining production industry today. After all, almost every company today is also a technology company in some form. Or as Marc Andreessen predicted as early as 2011: ‘Software eats the world.’ [2]

It would therefore be wrong to negate all the achievements of the agile movement and initiate a 180-degree turnaround. Rather, it is about learning from the mistakes of the agile movement. In addition to the manifold application and implementation errors of agility described above, one of the biggest mistakes has probably been that agility has become an end in itself. This is not least due to the fact that the term agility has been misunderstood and equated with the agile manifesto by many. As a result, agile software development methods came to the fore both in IT and beyond, and the original problem was increasingly lost sight of.

The further development of agility is therefore to refocus on the original problem. And in this context, that is: how do I create a highly efficient organisation in a VUCA or BANI world? So while the trendy term ‘agile organisation’ anticipated a solution and thus almost provoked application and implementation errors, I advocate a term for further development that focuses on a timeless problem: namely, how can my company achieve maximum performance? Or to put it another way: how do I create a high-performance organisation?

Continuous evolution towards a high-performance organisation

A high-performance organisation is one that gets the best possible performance out of the existing possibilities. It is comparable to our individual, personal development, where we also strive to be the best version of ourselves. A high-performance organisation is the best version of a specific organisation in its current context.

Achieving such a high-performance organisation is therefore also one of the core tasks of a manager, because it is their specific role to optimise the organisation for which they are responsible, regardless of whether it is a team, a department, a business division or an entire company.

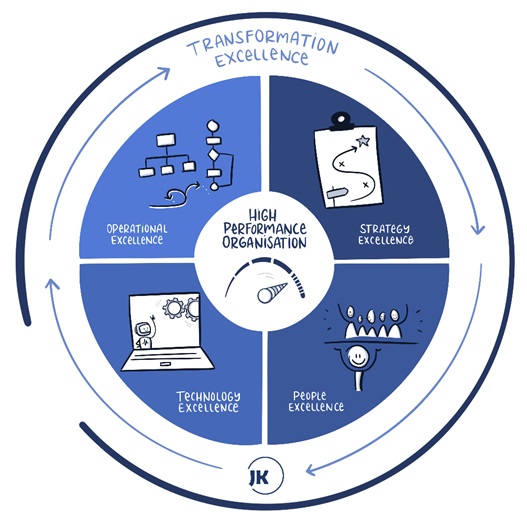

The disciplines of a high-performance organisation

How this high performance is achieved is very context-dependent. However, there are five central disciplines that an organisation must master and continuously develop in order to achieve optimal performance. This applies at the team level as well as through all scaling levels up to the entire organisation.

Discipline 1: Strategy Excellence

We are all familiar with the classic examples of failed strategies: Kodak, which missed the digital camera trend; Blockbuster, which missed the streaming offering; and perhaps soon Google, which is unable to respond to the trend of us increasingly replacing Google Search with tools such as ChatGPT, Co-Pilot or Perplexity.

An organisation that is stuck in an innovator’s dilemma and is not working on the right things is not only failing to realise its full potential. It is also endangering its own survival in the medium to long term. Accordingly, a high-performance organisation is characterised by excellence in strategy work. This includes not only strategic adaptability, but also the ability to implement successful strategies, business models or innovations.

Discipline 2: People Excellence

‘Clients do not come first. Employees come first. If you take care of your employees, they will take care of the clients.’ [3] This is not a quote from someone from Gen Z, but from Richard Branson. At the ripe old age of 74, he is one of the most successful entrepreneurs of modern times and no longer a Gen Z, who are often said to value an oasis of well-being more than entrepreneurial achievement.

And Richard Branson is, of course, far from being the only one who has recognised how important human performance is for organisational performance. A high-performance organisation is therefore also characterised by people excellence. This generally means that human performance is optimised. Among other things, this includes a performance-enhancing leadership culture, team development and also the empowerment of employees to acquire the skills necessary for implementing the strategy.

However, people are not machines, so optimisation of performance does not mean ‘squeezing the lemon dry’. Rather, it is about creating an environment in which not only employees can sustainably exploit their performance potential, but also the team. After all, the team as a value-adding unit is the most important group for a successful organisation.

Discipline 3: Technology Excellence

Let’s go back to the case studies of famous companies that have failed. In this group, of course, a prominent example should not be missing: NOKIA. While Steve Ballmer, then CEO of Microsoft, actually ridiculed the iPhone in 2007, thereby documenting his strategic misjudgment for posterity, NOKIA took the competition quite seriously. It was therefore not, or not only, a strategic misjudgment that brought NOKIA down. Rather, NOKIA’s technological architecture was not capable of keeping pace with this strategic development quickly enough.

An example of how it can be done differently is FACEBOOK or META. Often, a change in the market seemed to bring the giant to its knees, but time and again the company managed to develop its product thanks to a high level of technological excellence. Be it the attacks from Snapchat and other market companions, which could be fended off again and again because their features could be copied quickly and successfully. Or the switch from desktop to mobile use of the product. Or even Apple’s privacy settings, which restricted the tracking of apps. This caused the advertising accuracy of META products to plummet by 40%, which threatened the business model so substantially that META’s enterprise value fell by 26% or $230 billion in just one day. Since this slump about three years ago, the company value almost tripled by the end of 2024, because META was even able to display more accurate advertising than before the tightening of the privacy options on iPhones thanks to the use of AI.

These examples show that a high-performance organisation can hardly avoid also developing technological excellence. Not only when technology is as close to the core product as it is at NOKIA or META. Nowadays, there is hardly a company that does not use technology in its value chain. In addition, technology is arguably the biggest driver of change for companies today, which is why organisational technology expertise is indispensable. Accordingly, technology excellence includes, among other things, the economic use of new technology trends at all levels of corporate management. Such as artificial intelligence, for example. The use of technology for the automation and optimisation of service provision. Or, in general, the management of technology in the organisation, including the management of enterprise architecture.

Discipline 4: Operational Excellence

In the past, TOYOTA was often used as a prime example of operational excellence. After the Second World War, TOYOTA innovated its production process to such an extent that the Japanese carmaker was significantly better than its US competitors in terms of operational excellence.

This was not only an economic disaster for the Americans, but also fundamentally shook the national pride of the country that had produced Henry Ford, an automotive pioneer and thought leader in the scientific management theory (also known as Taylorism). From the 1970s onwards, countless Western management theorists and practitioners therefore studied what makes Toyota so significantly better than American carmakers. Many of these insights have been incorporated into lean management theory, which, as mentioned, is an important foundation of today’s management theory.

However, the world has moved on and become more complex. Many paradigms and practices of lean management are still valid. But the value-added production of many companies today no longer takes place on the assembly line, but in offices or home offices. One of the biggest differences is that the production process of today’s knowledge and service work is no longer as linear as it was on the assembly line back then. The resulting increase in complexity means that operational excellence must be thought of in broader terms than it was with TOYOTA. In this discipline, the focus is therefore not only on the process organisation, but also on the holistic operating model – the organisational operating system, so to speak. This includes the organisational structure, governance, collaboration practices, incentive systems, value creation processes, etc.

Many of the current methods that are advertised in connection with agility can be assigned to this discipline. Be it delivery models with a focus on IT such as SAFe, Scrum or LeSS. Structural models such as Holacracy by Brian Robertson or the Helix model by McKinsey. Or other collaboration and problem-solving methods such as Design Thinking, Kanban or Flight Levels. Accordingly, there are now many more or less successful practical examples of the various approaches:

- SAFe, for example, organises a huge annual conference where current showcase examples are presented.

- Scrum is standard in IT delivery and it is becoming more difficult to find an organisation that does not use it.

- Holacracy is mainly found in organisations where value is not added within the organisation, but directly at the customer, and therefore internal value creation work is negligible. Examples are therefore mainly agencies, Spitex companies or consulting organisations.

- The helix model, on the other hand, is being adopted by an increasing number of organisations thanks to the relationships of McKinsey consultants – often rather large companies with over 1,000 employees. Not least because other large (strategy) consultants are also copying the model inspired by Spotify.

All in all, it can be said that there are now enough practical examples of the many approaches that can contribute to operational excellence. However, in contrast to the situation at the time of TOYOTA, there is hardly a company that can be cited as a universal example.

Of course, there are companies such as Spotify, Gore, Amazon, ING, Bayer, Zalando or Netflix, which are repeatedly cited and referenced for their modern work in terms of operational excellence. In Switzerland, too, we have well-known companies such as Swisscom, Mobiliar and Axa that can be cited as pioneers. But a universal example like Toyota was 50 years ago is hardly possible today because the market dynamics for organisations have become much more complex and thus more context-sensitive. For organisations, this means that there is enough knowledge and examples to inspire how operational excellence can be developed. However, the challenge lies in implementing and continuously developing it in a way that is context-appropriate, so that the organisation not only succeeds in doing the right things – this is strategy excellence – but also in doing things right.

Discipline 5: Transformation Excellence

Continuous development is the fifth discipline of a high-performance organisation. This is because, on the one hand, the environment and the challenges are constantly changing. On the other hand, because an organisation never works perfectly and must constantly develop in order to improve.

One of the biggest mistakes that most organisations make today is that they only transform when it is actually too late. This results in a so-called stop-go transformation. The organisation realises that it has to change, initiates a major transformation programme, which in turn paralyses the entire value creation process because the organisation is preoccupied with itself and many employees first wait to see how the change will affect them personally. After a significant drop in productivity, the innovations begin to take effect in the best case. But only a short time later, the next transformation is already on the horizon and the game begins all over again.

The problem is not only that such large-scale transformations often fail due to their complexity and do not deliver the desired economic added value. Rather, the organisation is virtually permanently blocked by this stop-go approach and thus never enters a high-performance state.

Isn’t that a contradiction if continuous development is part of the DNA of a high-performance organisation, as shown? No, because the trick lies in the way transformation is understood. High-performance organisations make change the norm. This means that they are constantly changing a little bit so that it does not lead to a drastic drop in productivity because the organisation is blocked due to a disruptive transformation. Consequently, high-performance organisations position themselves in such a way that they can continuously develop the four disciplines of strategy excellence, people excellence, technology excellence and operational excellence without overburdening the system. How big or fast a change can be without overwhelming the system naturally depends on the organisation’s and its employees’ ability to change. Accordingly, a high-performance organisation also continuously develops the fifth discipline: transformation excellence.

Now, the objection may be that sometimes radical measures are needed in certain times. Yes, on the one hand that is true. The integration of two large banks, for example (such cases are also said to exist in Switzerland), is a radical change. In the case of radical changes, an attempt must be made to reduce complexity (in the breadth and depth of the transformation) to a minimum. So it makes sense not to tackle changes that are not absolutely necessary. Or to reduce the demands on the rate or quality of adaptation (done is better than perfect), in order to then improve step by step on this basis. On the other hand, high-performance organisations that have continuous transformation as a core competence basically avoid having to make such radical changes. In the hypothetical example with the two banks, at least one of them was probably not a high-performance organisation.

Conclusion: High-performance organisation as a continuous aspiration

In summary, it can be said that a high performance organisation represents the next evolutionary step after agile movement and addresses the challenges of a dynamic and complex (VUCA and BANI) world in a sustainable way. While agility often failed due to a lack of holistic transformation, a lack of contextual adaptation and insufficient empowerment, the high-performance organisation aims to overcome these deficits and make organisations more efficient in a holistic way.

A high-performance organisation is characterised by the mastery and continuous development of five central disciplines:

- Strategy excellence, doing the right things;

- People Excellence, realising the potential of employees and teams;

- Technology Excellence, realising the technological potential;

- Operational Excellence, doing things right;

- Transformation Excellence, enabling continuous adaptation and further development without disruptive breaks.

The high-performance organisation model shows how companies can take up the original goals of agility and expand them through a holistic approach, not only to remain sustainable, but also to develop their maximum performance in an increasingly networked and complex world.

Notes:

[1] Karlsruhe University of Applied Sciences: Study on agility: a lot of talk, little action

[2] Marc Andreessen: Why Software Is Eating the World

[3] Richard Branson: What Separates Successful Companies From All the Rest Comes Down to 1 Leadership Principle

This is a Top Blog Post 2025.

If you like the article or would like to discuss it, please feel free to share it in your network. And if you have any comments, please do not hesitate to send us a message.

Dr Joël Krapf has published two more posts on the t2informatik Blog:

Dr. Joël Krapf

Dr Joël Krapf has been supporting corporate transformations for over 10 years. He currently supports organisations on their digital journey as a senior manager at Accenture. Previously, he was Head of Lean Portfolio and Agile Transformation at Migros, the largest employer in Switzerland. Other positions include PwC and Swiss Post.

Joël holds a PhD in Agile and Transformation from the University of St. Gallen. He has published various books and articles on the topic of agility and is regularly invited as a keynote speaker at conferences. Around 30,000 people follow him and his posts on LinkedIn.

In the t2informatik Blog, we publish articles for people in organisations. For these people, we develop and modernise software. Pragmatic. ✔️ Personal. ✔️ Professional. ✔️ Click here to find out more.