The torch into the future

The most dangerous future is the probable one. Because it assumes that tomorrow will work the same way as yesterday.

Why is that? Let me start with a short story:

A few weeks ago, I was invited to a strategy day at a medium-sized company. Around fifty people were invited. Members of the management team, executives and sales staff. I was asked to give some impetus on megatrends and show what the future holds.

I presented developments that have long been reality in other parts of the world: dark factories in China that produce entirely without humans. Autonomous robot taxis in California. Tasks performed by civil engineers and architects that are already being taken over by AI today.

After the presentation, the managing director approached me. ‘Great presentation, really inspiring,’ he said with a smile. Then he added: ‘But that was pretty far-fetched, wasn’t it?’

Ironically, I had pointed out in the presentation itself that much of what is considered science fiction has long since become reality.

Later in the strategy day, the management presented its future strategy for the next three years. The existing product portfolio is to be strengthened and sales are to be driven forward in a disciplined manner. Because customers no longer come of their own accord.

What’s the problem, you might think? The company is thinking ahead. Yes, it even has a clear strategy.

But the probable future is only one of several possible futures. The Christmas story ‘When the future appears at Christmas’ highlights precisely this problem. Karl Meier, managing director of the medium-sized company CoolGrill, encounters three ghosts. They show him three futures: the probable, the possible and the desirable.

Karl lives in the narrow corridor of the probable future. He ignores everything else.

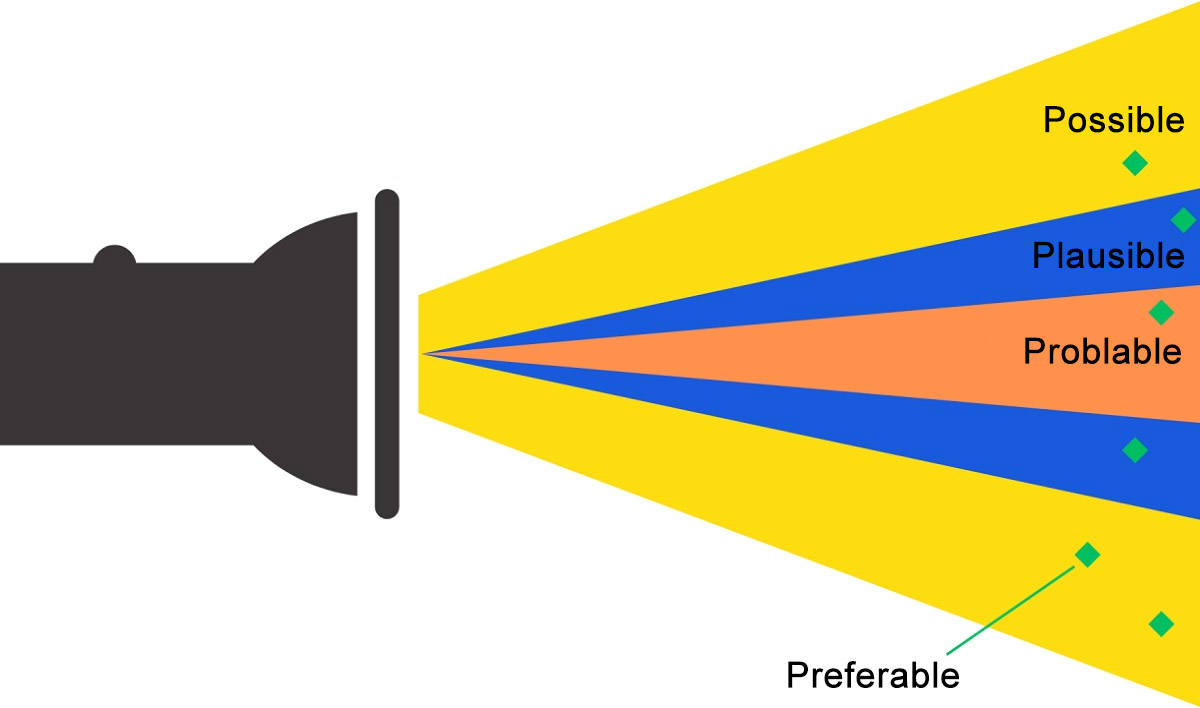

Futures Cone: Shining a torch into the future

The three spirits are inspired by the Futures Cone, a model developed by futurologist Joseph Voros. [1]

Imagine a torch shining from the present into the future. The further the beam reaches, the wider the cone becomes. And the more possibilities become visible. This cone of light can be divided into several areas.

Probable

The narrowest area, right in the middle. This is where a company ends up if everything continues as before. Same strategy, same framework conditions, same assumptions. Most business plans fall into this category. Plus five per cent, minus five per cent. Linear growth. The tried and tested is optimised.

Plausible

A little further out. This is where realistically conceivable alternatives lie if individual parameters change. New regulations, technological leaps, shifts in the market. This is where classic scenario planning comes into play.

Possible

Even further out. Developments with low probability but high impact. Wildcards and disruptions. What is often dismissed in risk analyses as ‘unlikely, but not impossible’ and then often forgotten.

And then there are the preferable futures. They can lie anywhere in the cone. These are the futures that need to be actively shaped, regardless of how likely they appear.

Figure 1: Futures Cone according to Joseph Voros

Why do most people and companies stay within the inner cone?

Our brain is a continuation machine, and for good reason. For most of our evolution, stability was essential for survival. Those who tried something new took a risk. Those who stuck with the tried and tested survived. These mental shortcuts are still deeply ingrained in our thinking today.

Status quo bias: stability pays off

Optimising what already exists takes significantly less mental energy than building something new. So we stay where we are and make the old better, faster and more efficient.

Nokia is a cautionary example. In 2007, the company was the undisputed market leader with around 40 per cent of the global mobile phone market. Even when Apple began to gain market share with the iPhone, Nokia continued to optimise phones with keyboards. The existing Symbian operating system was also consistently improved, even though iOS and Android had already created a completely new ecosystem in which phones became platforms.

‘We are strengthening our existing product portfolio,’ says the company from the opening example. The outcome of the Nokia story is well known.

While you are making your existing product lighter, cheaper or more efficient, someone else is building a business model that makes your product obsolete. Improving what already exists does not protect you from someone else reinventing the game.

Normalcy bias: It won’t be that bad

In addition, we systematically underestimate how drastic changes can be. Even when the signs are visible, our brain declares them to be exceptions. ‘It’s different for us.’

A good example is Thermondo. The start-up launched in 2013 with the aim of transforming the heating market. Buying heating online instead of waiting three weeks for an on-site appointment. The reaction of many traditional tradesmen was predictable. Buying heating online was a niche market, their customers wanted personal advice.

By 2017, Thermondo was Germany’s largest heating installer. In 2022, the company fundamentally changed its business model once again. From the largest heating installer to the largest installer of heat pumps. By 2024, Thermondo was no longer installing fossil fuel heating systems, but exclusively heat pumps.

Each of these developments was declared a special case in the industry. Their own region was special. Their own customers were different. The signs were there, but they did not fit into the picture of normalcy.

‘Pretty spaced out,’ says the managing director from the opening example about humanoid robots and dark factories. You see the change, but call it the exception. You wait for a return to normality. However, the new normality has long been on its way, just not in your own spotlight.

Linear thinking: the S-curve is difficult to see

There is another limitation to our thinking. Our brains are poor at grasping exponential developments. The well-known wheat grain legend illustrates the problem:

A king promises a wise man a reward. The wise man asks for wheat grains. One grain on the first square of the chessboard, two on the second, four on the third. Always doubling. The king mocks the supposed modesty. One, two, four, eight, sixteen grains. Thinking linearly, this seems harmless. After 64 squares, however, the king owes more than 18 trillion grains. More wheat than his entire kingdom can produce in a thousand years.

As early as 1965, Gordon Moore predicted that the number of transistors on a chip would double approximately every 18 to 24 months. [2] This prediction has been accurate for over fifty years. From calculating machines that filled entire rooms to powerful computers the size of a grain of sand.

The adoption of technologies also often follows an S-curve. At the beginning, little happens: high research and development costs, low usage. Then comes the steep part. Suddenly, user numbers grow exponentially. At some point, the curve flattens out again.

In 2018, GPT 1 was purely a research project by OpenAI and could generate simple texts. Hardly anyone took notice. In 2020, several thousand developers were working with GPT 3 via APIs. ‘Not yet ready for the mass market.’ In November 2022, GPT 3.5, better known as ChatGPT, was released. Two months later, it reached 100 million users and became the fastest-growing consumer app in history.

For four years, the curve remained flat. Outside the tech scene, hardly anyone took the topic seriously. Then the number of users exploded.

Back to the managing director from the opening example. He looks at the flat phase of the S-curve in humanoid robotics and thinks: We’re still a long way off.

In fact, there are only a few pilot projects today. Robots from Figure are working in production at BMW. 1X supplies a few select customers. The crucial question is not whether a ChatGPT moment is coming, but when! Or to put it another way: where are we on the chessboard right now? On square eight or nine, where we have a few hundred humanoid robots in research laboratories and pioneering companies?

Trapped in the cone of light

These three mental shortcuts keep us trapped in the narrow cone of light of the probable future. We optimise what already exists, while elsewhere the game is being reinvented. We declare every change to be an exception until the new normal has long since become reality. And we plan linearly, while the S-curve tips unnoticed into the steep part.

The probable future feels safe because it is familiar. It ties in with what we know, can measure and control. That is precisely where the danger lies. It assumes that tomorrow will work the same way as yesterday. It is not wrong, but it is incomplete. That is exactly why Karl Meier receives a visit from the spirit of the possible future. Katie shows him breaks, deviations and the improbable with a high impact.

Notes:

This is part 1 of a series of articles by Tobias Leisgang about the future. Part 2 is about the possible future and the realisation that the phrase ‘No one could have seen that coming’ is not true in most cases.

Tobias Leisgang is a moderator and companion for companies that want to boldly break new ground. If you’re still finding it difficult to get started, feel free to visit his website or contact him on LinkedIn to take the first few steps together. 😉

[1] The Voroscope: The Futures Cone, use and history

[2] Wikipedia: Moore’s las

Would you like to discuss the challenges of the future as a multiplier or opinion leader? Then share this post in your networks.

Tobias Leisgang has published more posts on the t2informatik blog, including:

Tobias Leisgang

‘The future is the only place I’ll spend the rest of my life’ – Charles Kettering was right and Tobias Leisgang takes this quote very seriously. After studying electrical engineering, he developed semiconductors, researched the latest technologies with global teams and made the supply chain of an automotive supplier fit for the future.

Today, he helps small and medium-sized companies develop sustainable business models – with a great deal of foresight and a dash of pragmatism. Because there are often many decisions to be made between good ideas and their implementation – and that’s exactly where Tobias comes in: in ‘Kopf & Bauch – Der Podcast der Entscheidungen’, he provides exciting insights into how to make them.

And because standing still is not an option for him, Tobias continues his journey as a future shaper – not in a fancy suit, of course, but as a student in the future design programme. After all, who says you can never learn enough?

In the t2informatik Blog, we publish articles for people in organisations. For these people, we develop and modernise software. Pragmatic. ✔️ Personal. ✔️ Professional. ✔️ Click here to find out more.