Why don’t employees do what they are supposed to do?

A change of perspective on apparent resistance from employees

A project is not progressing, agreements are not being kept, tasks are not being completed, and the manager asks themselves: Why aren’t they just doing what was agreed?

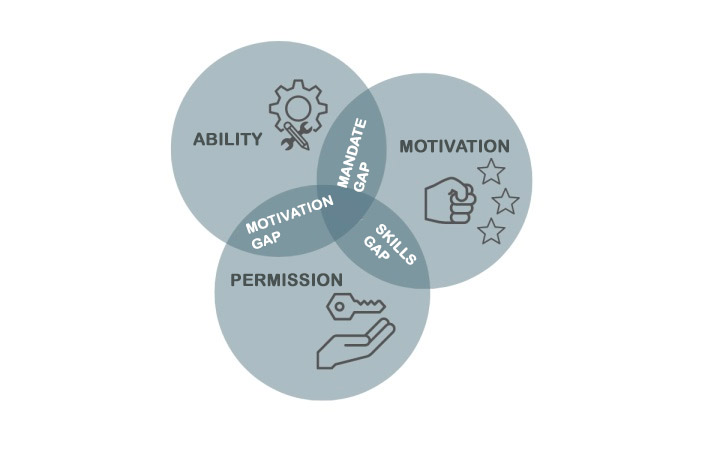

In moments like these, the first reaction is often frustration or the judgement: they lack motivation! But the supposed resistance often turns out to be a symptom of completely different causes. It is worth taking a new perspective with the help of a simple but effective triad: ability, permission and motivation.

- Does the person have the skills and professional expertise? CAN they do what is required?

- Do they have the necessary decision-making authority? ARE they allowed to do it?

- Are they motivated to take on the task? DO they even want to?

Not being able to: when skills are lacking, pressure doesn’t help

The skills gap

An example from my everyday project work:

There is a lot of friction in a software development team. The requirements delivered regularly fail to meet the expectations of the stakeholders. Constant reworking or complete reworking is necessary. This costs time and nerves. The project manager is at the end of his tether: ‘I’ve told the product owner dozens of times that he needs to talk to the stakeholders. Why doesn’t he just do it!’ he says to me when I join the project.

I get to know the product owner and quickly realise that he is at least as frustrated as the project manager. We go through the user stories and I accompany him to a meeting with stakeholders. He listens to the requirements and writes everything down. But he doesn’t ask any questions. He has no systematic approach to recording the issues. He simply lacks the methodological tools to gather requirements in a structured way. It’s not unwillingness, but a lack of competence.

What can you do as a manager in such a case?

- Check that the role is a good fit in terms of technical and methodological requirements. Does the employee have all the technical, interpersonal and methodological skills they need?

- Provide targeted development: whether external training, coaching by colleagues or accompanied practical experience, learning needs structure.

- Encourage openness: Technical gaps are no reason to lose your position. Employees must feel confident enough to address them. Only then can learning take place.

Management tip:

‘What skills can you develop further to enable you to perform your role really well?’ This question opens up room for development potential without reproach.

Not allowed: when the system blocks the scope for action

The mandate gap

An example from my everyday project work:

A security risk has been known about for weeks. It has been reported internally several times and escalated, but nothing happens. The department head is angry: ‘Why isn’t the system administrator finally taking care of it? That’s what I hired her for!’ He doubts her competence. Or her will.

In conversation with her, it quickly becomes clear that she has recognised the problem and can analyse it. She wants to take responsibility, but she is not allowed to. Internal guidelines prevent changes to security-related components without approval from several authorities. She is trapped in the system – powerless and frustrated.

What can you do as a manager in such a case?

- Question decision-making powers: Are there unnecessary hurdles that prevent personal responsibility?

- Simplify processes: Establish clear, practical rules for typical cases.

- Empower the employee consciously: Delegate responsibility and the corresponding scope for action. Let the employee know that you support her decisions.

Management tip:

‘Who or what is currently preventing you from solving the problem?’ This question shifts the focus away from the individual and towards the system.

Not wanting to: when motivation is lacking, expertise is of no help

The motivation gap

An example from my everyday project work:

A new employee has been with the team for weeks, but she is struggling to settle in. There are still gaps in her understanding of the processes, and her onboarding is taking a long time. Her buddy is an experienced senior developer who is highly skilled and ideally suited to explaining the topics to the newcomer. But it’s not working.

In conversation, it becomes clear that the senior employee simply has no desire to train her. ‘I took it on because it’s my area of expertise. But to be honest, I’d rather code in peace than explain everything to someone.’ The task does not match his motivation, and the new colleague is the first to notice this.

What can you do as a manager in such a case?

- Determine the fit between the task and motivation: Those who are not intrinsically motivated will not do a good job, even if they could in theory.

- Involve the team: Are there others who enjoy this task? Can they provide support or take over the task entirely?

- Recognise different strengths: Not everyone has to do everything. Good leadership makes targeted use of individual talents – in another project or department, if necessary.

Management tip:

‘How can we get this task done without you being too involved?’ This question does not relieve the employee of their responsibility, but it does relieve them of the operational implementation.

Conclusion: Leadership begins with questions, not demands

Why don’t employees just do what they’re supposed to do? This question sounds simple, but the answer is complex. Those in leadership positions must face up to this complexity. Behaviour in the workplace is rarely purely voluntary. It is much more often the expression of structural, technical or motivational obstacles and can be understood systematically and humanely using the triad of ability, permission and motivation.

Not being able to do something indicates a lack of skills, methods or experience. But where deficits become apparent, it is not failure that is at play, but rather a call for development. Professional gaps are not a weakness, but a natural part of every learning process. Leadership here means creating space for growth without losing face.

Not being allowed to do something makes it clear that even the most motivated and competent employee can fail if structures, processes or a lack of authority hold them back. This calls for leadership that questions rules, adapts systems and consciously delegates authority. Those who want responsibility must not only be given it on paper.

After all, not wanting to do something reveals that without inner commitment, any action will remain superficial. Motivation cannot be forced, but it can be understood, strengthened and used in a targeted manner. Good leadership recognises that not everyone can do everything equally well, and that is okay. What counts is using talents correctly, assigning tasks appropriately and keeping the dialogue open.

Ability – permission – willingness is more than an analytical model. It is an invitation to change perspectives, to move away from quick judgements and towards genuine root cause analysis. It requires managers to be willing not only to evaluate behaviour, but also to develop an understanding of conditions and motivations. It requires curiosity, empathy and the courage to reflect on oneself: What have I contributed or failed to do as a manager?

My plea: If something is not going as planned, don’t start with criticism, start with questions. And the right ones at that:

- What does this person need to be able to develop their potential?

- What is currently blocking their self-efficacy?

- What really motivates them – and what might not?

This creates a leadership style that not only ‘leads’ people, but empowers them. It doesn’t just demand performance, but creates the conditions for performance.

Notes:

Marei Bauer supports managers in practising effective, people-centred leadership with structure, clarity and trust. If you recognise your team’s issues, feel free to write to her on her website or on LinkedIn. Together, you will surely find out what your employees really need.

This is a Top Blog Post 2025.

If you like this article or want to discuss it, please share it with your network. And if you have any comments, please do not hesitate to send us a message.

Marei Bauer has published another article on the t2informatik Blog:

Marei Bauer

Marei Bauer is a systemic business coach with roots in consulting and classic project management. Today, she shapes trusting collaboration and people-centred leadership in organisations. Her focus is on self-organised teams, new understandings of leadership and the question of how to create working environments in which people can develop their potential.

She combines analytical thinking with a keen sense of interpersonal dynamics and organisational development. Her expertise also includes designing and facilitating workshops and training courses. In these, she initiates sustainable change and develops viable working structures together with those involved.

In the t2informatik Blog, we publish articles for people in organisations. For these people, we develop and modernise software. Pragmatic. ✔️ Personal. ✔️ Professional. ✔️ Click here to find out more.