Organisations develop by themselves

Why it’s good when the tried and tested suddenly stops working

“Nothing is as constant as change” was recognised by Heraclitus more than two millennia ago. And in the dynamic world of software development in particular, change is a constant.

Organisations operating in this fast-paced playing field often discover that the processes and strategies that once brought them to the top suddenly become shackles on their growth. But is this really a cause for concern? Or does this realisation not rather harbour a hidden opportunity for reinvention and improvement?

Change is annoying

Maybe you’re like me: change is annoying. As stimulating and exciting as I actually find new things, I really like it when I know processes, can do things by heart and know that everything around me works perfectly.

But this is usually the real problem: in my career as a serial founder, entrepreneur and Agile Coaches, I have worked in and with organisations in various industries, in different countries, from start-ups to corporations. What they all have in common: Sooner or later, things just didn’t work perfectly. It rumbled, it crunched, there were interruptions or things actually went wrong.

As different as the challenges and solutions were: At some point, I realised that these changes in structures, processes, technologies and leadership dynamics were not only unavoidable at the time, but also essential for the sustainable success of the respective organisations.

Recognising the need to adapt

When I founded my last start-up, there were just four of us: Each with a clear expertise, we worked together in one room and often even on the same screen. I always knew what my colleagues were working on and what was on their minds. The number of defined processes we had back then: Zero. And we were successful: we won various awards, applied for patents and found investors.

Three years later, I had reached my limits: Over 40 employees on 2 continents, almost all decisions ended up on my desk at some point, and if I wanted to know how many raw materials we still had in stock, I had to send someone out to count them. The concept of mental load was still unknown to me at the time, but I realised that it no longer worked like that.

The levers for effective change: five dimensions of organisational design

This meant that I had at least mastered the first challenge for managers, namely recognising that change is necessary. And as a managing director, I also had the opportunity to actually initiate change.

Both are not a matter of course: symptoms such as management overload, delays, quality problems or employee dissatisfaction are often dismissed as temporary difficulties instead of being understood as signs of more profound structural problems.

In traditional hierarchical organisations in particular, this is often not only exemplified but also expected. If you want to make change possible, you often need allies or at least have to understand the central dimensions of organisational design yourself and be able to assess where you can actually be effective with your decision-making authority and your network.

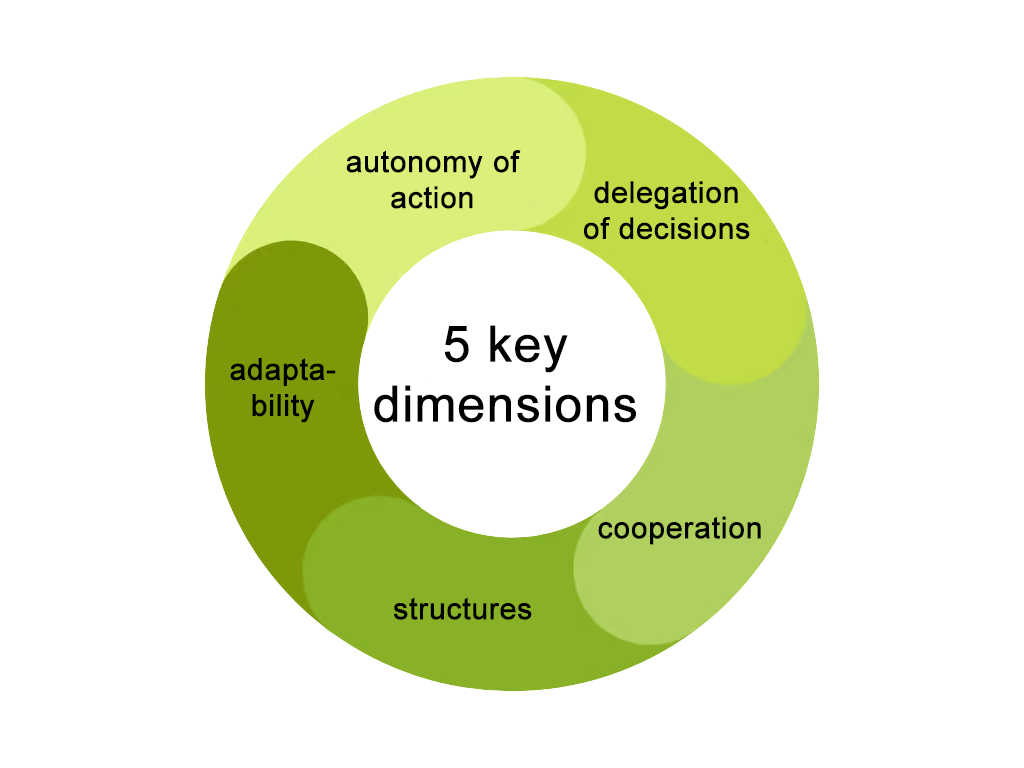

A look at the five dimensions of autonomy of action, delegation of decisions, cooperation, structures and adaptability can help here:

The five key dimensions of organisational development (graphic: C. Fiechter)

1. autonomy of action: formalise or enable?

At the beginning of our start-up journey, we managing directors had access to all the information that existed in our company on any given issue at all times. As a result, we were able to make quick and usually good decisions ourselves. As the number of employees increased and the range of relevant topics grew (hand on heart: how many of you have ever heard of a food contact materials regulation?), we were suddenly no longer the experts for our product, but the bottleneck for procurement, production and sales. We no longer had the solution, we were the problem.

What we see at this point in many companies is the reflex to define processes in the form of instructions: If X happens, do Y; if you want holiday, get request Z signed by your team leader. This formalisation offers a high level of transparency, but at the same time offers employees little room for manoeuvre. And: Formalised processes are usually rigid. They are rarely questioned and are often only adapted once they have been noticeably affecting the organisation’s value creation for some time.

The alternative to this is to empower employees, i.e. to create a space in which they can make decisions in the interests of the company based on their expertise and the information available to them. This requires a clearly communicated goal and clearly defined guard rails. The guidelines determine how free the employees are in their decisions: Do we only supply customers in Germany, throughout the EU or worldwide?

The target helps to make the decision: Should I give a higher discount to win a particular customer? This allows employees to judge whether and to what extent a particular decision contributes to the set goal. And they have the psychological certainty that they can actually make this decision.

2. delegation of decisions: adapting the decision-making process

In “Turn the ship around”¹, David Marquet describes how, as the captain of a submarine, he took the decisions to where the information required for the decision was available: “Don’t move information to authority, move authority to the information.”

This is not always easy, especially in a volatile environment: what if parameters or internal company requirements change quickly? If, as a manager, I adjust my goal at extremely short notice or the parameters change at short notice, employees can easily be overwhelmed and, as a manager, I can hardly delegate clearly.

We have therefore used different approaches in my start-up: In production, where the goal and framework were clear, the employees decided for themselves how to organise themselves and, for example, how to allocate them to the machine and work steps. In the case of decisions that had a massive impact on the business figures, such as the procurement of a special machine for production, we made the final decision as managing directors: Does this fit in with the status of our negotiations with investors right now? Is the impact on cash flow acceptable to us? All decisions about technology, potential contractors and specific requirements for such a machine remained with our engineers, who were able to offer us suitable options for various scenarios (e.g. bootstrapping vs. successful financing round) based on their expertise.

But here, too, the decision was made where the information was. And where the most fundamental responsibility of a managing director lies, namely in the area of solvency.

3. cooperation: rethinking collaboration

But it wasn’t just the decisions we had to make that changed. Our cooperation also changed gradually at first: while the four of us were initially aware of all the relevant issues and supported each other, over time specialist positions were created. As the number of employees increased, each individual became less and less aware of what the others were working on.

But how do I share information across departments? How do I coordinate without wasting time and how do I liaise effectively?

In most larger companies, the standard answer to this is “regular meetings”. And this idea had rather negative connotations for me: tedious, unproductive, doesn’t create real understanding, delays decisions…

So we only use meetings where they make sense for us: To work out content or strategies together, to share certain information with everyone and leave room to clarify uncertainties, and to bring everyone around the table at regular intervals.

For our day-to-day work, we rely on cross-functional teams and physical proximity. Our process engineer and our industrial designer, for example, had a shared workshop office with a glass front facing production so that they could intervene at any time. At the same time, they were also able to directly experience the consequences of their decisions for production and were able to incorporate this experience directly into their future work. Graphic design, marketing and sales shared an office, which meant that sales was always informed about current marketing campaigns or changes to our website, and feedback from sales (who were also responsible for customer service) was directly incorporated into the design of flyers or our online shop, for example.

What we have seen here and also see time and again in larger companies: informal knowledge and information exchange beats formalised information exchange hands down when it comes to knowledge acquisition, contextual understanding and incremental changes.

4. structure: being determines consciousness

The insight that the communication structures of an organisation are reflected in the systems developed by this organisation (e.g. software, but also non-trivial physical products) was established by Melvin Conway as early as 1968 (the so-called Conway’s Law) and has since been confirmed by various studies.

So if I want to change the systematic design of a product, I have to create the corresponding mirror-image organisational structures. Have you ever seen a company that develops software according to a layered model? Let me guess: A different team was responsible for each layer, development was sequential, building on each other, and the planning horizon was certainly not less than a year. If you now want to speed up your development and therefore parallelise it, it is not enough to simply opt for a microservice architecture. You also need to change your structures and establish cross-functional teams that coordinate in an appropriate manner.

I am far from seeing frameworks such as Kanban or Scrum as a panacea. What fundamentally helps is to look at value creation as a whole and to regularly scrutinise whether our goal has possibly changed and whether we are still on the best path to achieving it.

In the start-up, we had a surprisingly effective tool that forced us to ask ourselves precisely these questions: our business plan. Due to our capital requirements as a manufacturing company and the corresponding interaction with potential investors, we were forced to regularly update our business plan. At the same time, we realised which of our assumptions had been confirmed and what new insights we had gained in the meantime. And we were also able to clearly understand when we had underestimated the effort and duration of development or sales processes and learn from this.

5. adaptability: learning as a core competence

And this is exactly where the key lies: learning from it. As employees, so that we can do our daily work better. And even more so as managers, who ultimately define the actual structure and processes of the organisation through their behavior.

None of you would think of equipping an organisation on the drawing board with processes and rules that do not fit the product range, the size of the organisation or the competitive environment. When we talk about historically evolved processes, we mean exactly that: at a certain point in time, this organisation setup was the best decision we could have made. And at the same time, we would often make different decisions at today’s point in time, with today’s circumstances.

It doesn’t matter whether you learn an instrument, start jogging or change your organisation: It won’t be easy for you (or the other members of the organisation) at first. If you still want to be successful, there is a clear logic: if you find something difficult, you need to do it more often. In future, try not just looking at what you can improve in terms of output or artefacts such as your products. Instead, consider every time what small changes to rules, processes or responsibilities could help you to create even more or even easier value in the future.

Or to put it in more flowery terms: strive to build flexibility into the organisation’s DNA.

How do you use the levers in practice?

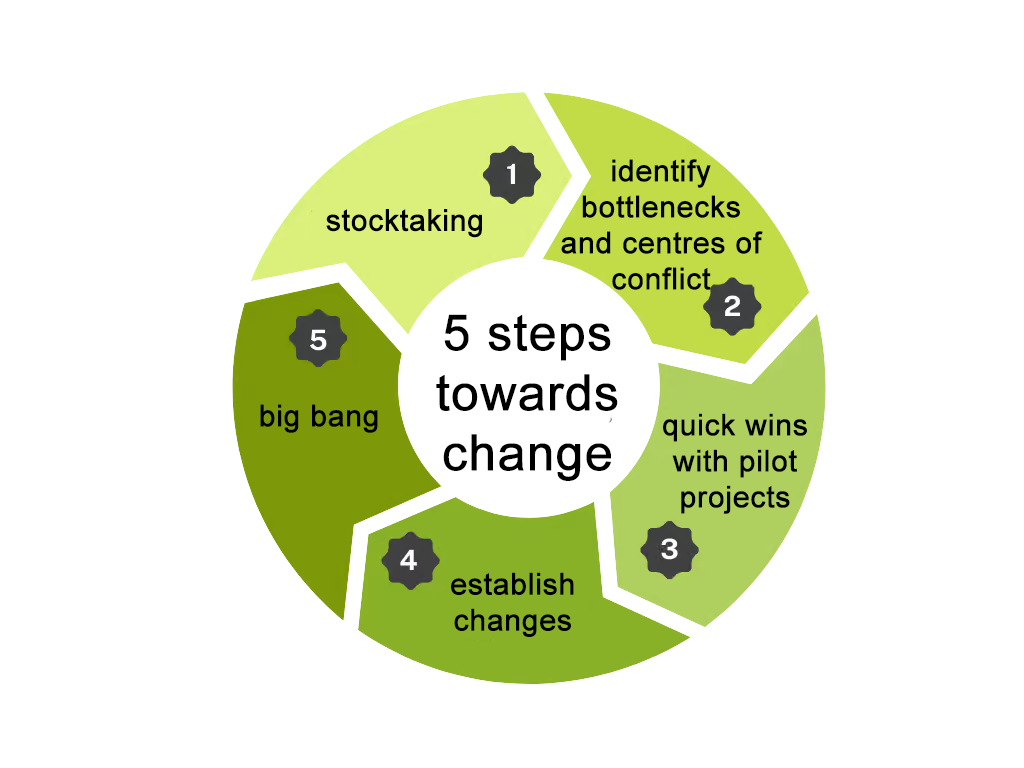

In organisational development projects, we often see the search for areas that are not working well in order to develop and implement change measures there. However, this regularly leads to insular optimisations and not to real further development of the organisation: for example, procurement may work faster and more effectively afterwards, but other employees have to spend more time filling out applications and obtaining approvals. To avoid this, an overarching 5-step approach based on value creation has proven its worth:

5 steps towards change (graphic: C. Fiechter)

1. stocktaking

Where and how am I currently creating value in the organisation? How effective am I at this? How fast and efficient am I? Outline the value creation processes and interactions. In doing so, collect the relevant data for a holistic assessment of value creation, such as error rate, customer complaints, conversion rate, net promoter scores, throughput time, idle times, but also employee satisfaction and sustainability.

2. identify bottlenecks and centres of conflict

Where do things take a particularly long time? Where do we have capacity utilisation rates above 80%? Where are there recurring coordination loops? Where is value creation being held up by multi-stage approval processes? Start by looking for symptoms, not solutions, and by no means for culprits. Blame is only helpful as a concept if you see uncertainty and fear as central management values.

3. quick wins with pilot projects

Solutions are often obvious when you zoom out of your day-to-day business and have the time to look at the big picture. Set up two to a maximum of three independent pilot projects to address one or more of the previously identified problems. The primary objective here is not maximum organisational development, but visible project success, a quick win, so that these pilot projects achieve a knock-on effect. Therefore, make sure that the initial and target situations are measurable, that those involved have all the necessary decision-making powers and are not dependent on third parties. And, above all, that all project participants take part in this pilot voluntarily and thus make project success even more likely through their intrinsic motivation.

4. establish changes

Give your employees and the organisation the time to experience that change is not a threat. Keep working on your organisation and celebrate victories and successes. Thank your employees for successful changes and show appreciation for the efforts that are always required. The more positively your employees experience change processes, the faster a learning and constantly developing organisation will emerge.

5. big bang

Sometimes evolutionary and incremental changes are not enough to remain competitive under significantly changing parameters. If your organisation already has long-term positive experience with change, you will be able to restructure your entire organisation to meet the new requirements based on a comprehensive inventory as described under 1. and 2.

Conclusion: Why the tried and tested cannot work in the long term

When the tried and tested works in the long term, it often means one thing: nothing has changed. In other words, the technology used by the organisation has not evolved, customer requirements for products and collaboration have not changed and the political, regulatory, sociological and economic business environment has remained exactly the same. This still means that the organisation has not evolved. So no additional or new employees, no new products, no new knowledge or experience, no new skills.

If you understand the development of organisations as a natural process that brings challenges and opportunities, you can deal with it constructively.

If tried and tested methods suddenly stop working, this is not a sign of failure, but a call for adaptation and improvement. The targeted design of the five key dimensions of autonomy of action, delegation of decisions, cooperation, structures and adaptability enables you to create a resilient, adaptive and thus future-proof organisation.

By learning as a leader to recognise the signs, respond flexibly to change and promote a culture of learning, organisations can not only survive in the long term, but also thrive in fast-moving industries such as software development.

Notes:

If you would like to find out more about Carolin Fiechter, it is worth taking a look at an interview (in German) that recently appeared on Colenet blog. There she talks about her experiences during her time as founder and managing director. And if you want to get in touch with her, simply write her a eine message or visit her LinkedIn profile.

[1] David Marquet: Turn the ship around

[2] Melvin E. Conway: How do committees invent

Matthew Skelton and Manuel Pais describe how organisations can structure themselves to create value while remaining adaptive in Team Topologies: Organizing Business and Technology Teams for Fast Flow.

If you like the article or would like to discuss it, please feel free to share it in your network. And if you have any comments, please do not hesitate to send us a message.

Carolin Fiechter

Carolin Fiechter is an agile generalist with in-depth experience, particularly in innovation management and in manufacturing companies, but also with many years of practical experience in knowledge transfer and personnel development.

As a business economist, she has a background in organisational development and management. During her studies, she became enthusiastic about the principles of the Toyota Production System and immersed herself deeper and deeper in the world of Lean and Agile. In her own company, she organised production according to Kanban and used Scrum to manage the organisation’s IT.

She was particularly impressed by the transparency and self-organisation of these approaches as well as the appreciation of all those involved and the resulting commitment and dedication: meaningful work that feels good also leads to high-quality solutions.

Today, Carolin Fiechter works as a Scrum Master and Agile Coaches at Colenet. She enthusiastically supports companies, advises at an organisational level and tries to make change possible.